More of it than we think

Andrew Steeds has been involved with the Migration Museum as a volunteer, trustee and as our Projects Manager for the best part of a decade. His many responsibilities have included creating and overseeing our blog. He stepped back from our core staff team at the end of 2020, although he will continue to work with us on a freelance basis and to be closely involved in our future activities and developments. In this sign-off blog post, he explains why the idea of a national Migration Museum for Britain resonates so strongly with him.

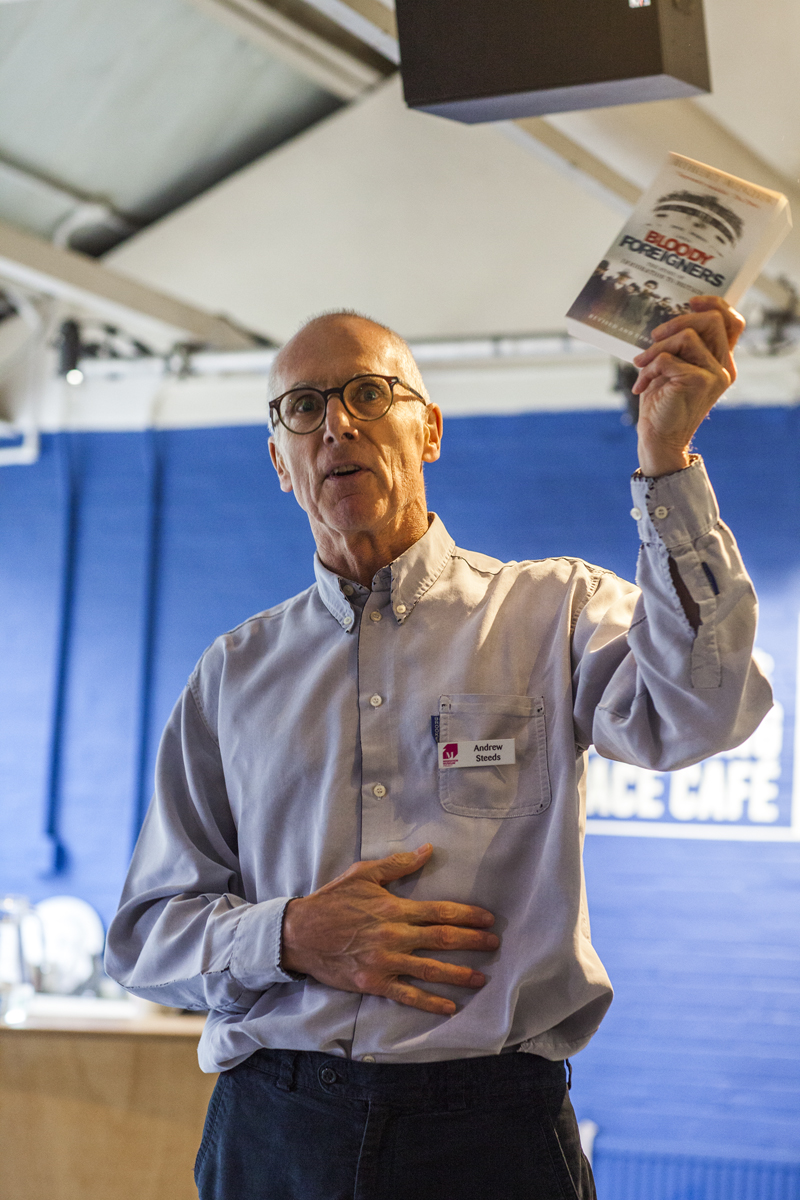

Andrew introducing a talk by Robert Winder as part of our Family History Day at the Migration Museum at The Workshop in 2019 (Image © Migration Museum)

At the end of last year, I left the payroll of the Migration Museum. I’ve been involved in the Museum – as volunteer, trustee and employee – for the best part of ten years. In those years, the organisation has grown from an idea to a physical entity and a huge community of supporters, whose belief in and excitement about our idea provides the rocket fuel we need when times are tough.

When I joined the Museum, nobody asked why I should be interested in doing so. The belief in the idea was so intense, maybe, that it was assumed that everyone involved was bound to be enthusiastic about it. Bit by bit, though, as our events and exhibitions attracted more and more people, visitors and supporters asked me what my migration story was and, implicitly, why I – a white, middle-class man now in his late 60s – should be so passionate about an idea that wasn’t obviously ‘for me’.

One of the main aims of the Museum, of course, is to create a space, a place and a face for people and communities who have been under- or unrepresented elsewhere. There have been countless instances over the past decade when people comment on how much it has meant to them to see ‘their’ story featured in our exhibitions. We have the opposite as well, of course: visitors who feel that their story has not been given the prominence in our exhibitions or activities it deserves – we counter that by saying that, until we have the funds and the space to tell ‘all our stories’ (the strapline for the Museum that we started with, and which still applies), we cannot cover the waterfront in every exhibition and there will sadly always be stories and perspectives that we are unable to feature as fully as we’d like to. But that aim – of creating a space in which people can tell their own story in their own words – remains a guiding principle for us.

But I am not a migrant, and neither were my parents or my grandparents. One of my cousins has traced our family tree back into the 18th century, and we still can’t find any immigration history. The only migration history I can find – other than the partners of my nephews and nieces – is of people leaving the UK in search of better lives abroad, inevitably not always for the soundest of reasons.

So why should I be interested in the Museum?

Because everything about it resonates with me and electrifies me with its truth: that the ‘we’ who populate Britain has always been polyvalent; that – if you take the long view (and we do) – we all come from somewhere else; that we are richer, healthier and more interesting because of the variety of who we are; that movement is as natural to humans as the urge to put down roots; that where those roots go down is a matter of chance, not right; that people tend to move from a place of personal stability only if they are compelled to do so; and that a measure of a country’s humanity is its ability to reach out a supporting hand to those who are compelled to leave their home.

And I (and we) also believe that the stories that, until relatively recently, were told about Britain’s past are not the full story and don’t take account of the awkward and complex relationship between that country and others around the world; that these stories are richer and more interesting than the ones certainly that I was taught at school; that the very idea of Britain and Britishness is, and always has been, a work in progress; that what we have in common is always more important than what divides us; that a community that is closed in on itself stagnates whereas one that is open to outside influence is renewed; that, whether you like it or not, learning to live with one another is preferable to fighting each other; and that, if we don’t learn to live with one another, we are basically stuffed.

It’s a bit of a rag-bag of reasons, that – but then so too are ‘we’ as a people and so too is our history. And that diversity, that plurality, is something that it feels more than ever important to display, to communicate, to build a museum around. In an earlier life as an English teacher, one of the books I taught from took its title from the last three words of this stanza (from Louis MacNeice’s poem ‘Snow’) and the excitement and exuberance of these lines is what I have felt working for the Migration Museum, and will continue to feel in my now semi-detached position:

World is crazier and more of it than we think,

Incorrigibly plural. I peel and portion

A tangerine and spit the pips and feel

The drunkenness of things being various.

Andrew (centre) and Migration Museum team members remove a vinyl at the end of our initial run of our Call Me By My Name: Stories From Calais and Beyond exhibition in 2016 (Image © Migration Museum)

Leave a Reply