Exploring the migrant history of Victorian East London

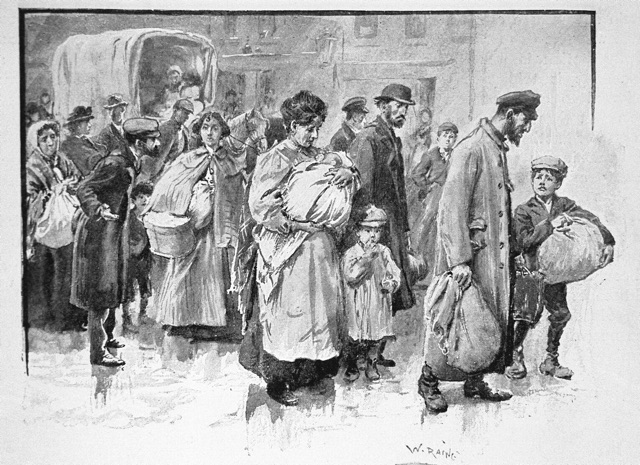

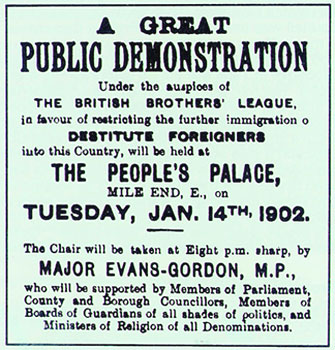

What was the attitude of the Victorians to immigration, particularly Jewish immigration? What was the mood of the country leading up to the passing of the Aliens Act in 1905? And what parallels are there between the experience of immigrants then and now, one hundred years later? The focus of this guest blog is Israel Zangwill and his late-19th-century book Children of the Ghetto; Nadia Valman, who has created an app that allows people to explore the Spitalfields area through the medium of the book, flags up a surprising number of parallels between the two periods.

Children of the ghetto

Israel Zangwill’s 1892 novel Children of the Ghetto is a landmark publication in English literature: the first Victorian novel to offer an insider’s perspective on immigrant lives in London. It offered the reader a wide social panorama, including rabbis, schoolteachers and philanthropists, garment workshop bosses and machinists, socialist organisers and poets, immigrant parents and English-born children. Published to great acclaim at a time of rising popular feeling against immigration, the novel aimed to make a significant political intervention by fostering understanding of a mostly voiceless migrant population.

Zangwill was in a unique position as a writer. He had lived most of his childhood in Spitalfields, the area of east London where tens of thousands of Jews, fleeing pogroms, expulsions and economic restrictions in the Russian empire, had settled during the 1880s and 90s. As a teacher at the Jews’ Free School there, he worked among the children of immigrants, most of whom entered school speaking no English. But as a graduate of London University who had moved to Bloomsbury and renounced religious practice, he also observed the Spitalfields Jews at a distance. His novel documented the close ties felt among people who, he wrote, had been forced to live in isolation for centuries, and could not easily shrug off the weight of that history.

Children of the Ghetto blasted onto the literary scene in the year of a general election in which immigration was a hot political topic. Back in the early 1880s, there had been widespread sympathy for the plight of Jews escaping persecution and destitution, and large protest meetings in cities all over the country condemned the Russian pogroms. Soon, however, attention turned to the social impact of immigration. Spitalfields, often referred to as the ‘Jewish colony’, attracted the fascinated gaze of sociologists and journalists. ‘My first impression on going among them,’ wrote Mrs Brewer in the Sunday Magazine in 1892, ‘was that I must be in some far-off country whose people and language I knew not. The names over the shops were foreign, the wares were advertised in an unknown tongue, of which I did not even know the letters, the people in the streets were not of our type, and when I addressed them in English the majority of them shook their heads.’ Others reacted with antagonism rather than bewilderment. The anti-immigration campaigner Arnold White declared that, unlike Christian refugees to England, Jews formed ‘a community proudly separate, racially distinct, and existing preferentially aloof … A danger menacing to national life has begun in our midst,’ he warned, ‘and must be abated if sinister consequences are to be avoided.’

As with other immigrants before and since, the Jewish immigrants of the 19th century introduced new tastes and refinements to London.

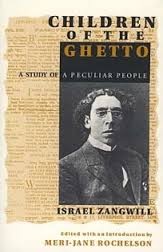

By the early 1890s a group of Conservative back-benchers were increasing pressure on the government to control immigration. The failure of their efforts in the following years has been attributed by some to the impact of Children of the Ghetto. But rising unemployment and discontent at the end of the decade provided the opportunity for two East End Conservative MPs to form the British Brothers League, which aimed to galvanise local support. A mass rally in January 1902, held at the People’s Palace, Mile End Road, was advertised as a ‘great public demonstration in favour of restricting the further immigration of destitute foreigners into this country’.

The British Brothers’ League was formed in 1902 to campaign against immigration; it was organised on vaguely paramilitary lines. Dribbling into obscurity in 1923, the League was in many respects the precursor of the British Union of Fascists, which had a significant and unsavoury presence in the 1930s.

It was partly in response to this popular hostility that the first immigration restriction act for a century was passed in Britain – the Aliens Act of 1905. The Act, while retaining the right to asylum on political or religious grounds, gave government inspectors power to ‘prevent the landing of undesirable immigrants’, including ‘invalids’ and ‘paupers’ – those who could not show that they were capable of supporting themselves – and thus excluded not only the sick and elderly but also those who arrived destitute, often having been conned or robbed of their assets on the journey.

There are many resonances between popular anti-immigrant feeling then and now. In the early 20th century, it helped to channel and defuse Eastenders’ anger at their chronic poverty and insecurity. Jews were accused of lowering the standard of living with ‘sweatshops’ – small workshops characterised by poor working conditions, long hours, low pay and seasonal fluctuation, and of causing the housing shortage that had led to extreme over-crowding. Yet in fact both problems were rife in the East End long before the Jews’ arrival. Hostility to immigrants came from pervasive lack of understanding about the real economic causes of local unemployment, such as trade depressions, mechanisation, and competition from manufacturers in the provinces.

In this context, there was considerable pressure on Israel Zangwill to produce an uplifting account of Jewish Spitalfields, countering misconceptions and demonstrating how Jewish immigrants were contributing positively to the economy and living pious, law-abiding lives. That pressure is evident in aspects of the immigrant subculture that he deliberately left out of the novel: the gang violence, the prostitution, and gambling clubs.

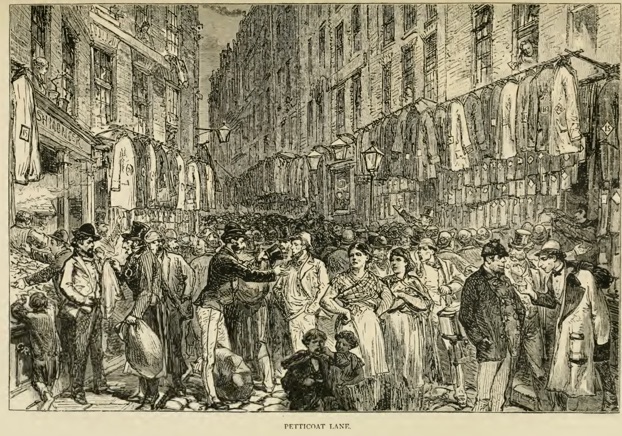

Nonetheless, Zangwill took a bold stand against a number of contemporary stereotypes. Petticoat Lane market, for example, at the heart of the immigrant area, was invariably associated in the Victorian press with danger and dodgy dealing, but it has a very different meaning from Zangwill’s perspective. He describes Petticoat Lane as a place where Jews of all social classes congregate to experience the smells and tastes that remind them of their roots.

Petticoat Lane, 1878.

‘The Lane was always the great market-place,’ he writes, ‘and every insalubrious street and alley abutting on it was covered with the overflowings of its commerce and its mud … The famous Sunday Fair was an event of metropolitan importance, and thither came buyers of every sect … A babel of sound, audible for several streets around, denoted Market Day in Petticoat Lane, and the pavements were blocked by serried crowds going both ways at once.’ In his account of the market, Zangwill emphasises its vitality and vulgarity. The distinctive dynamism of immigrant culture, for him, was precisely what was valuable about it. But the market was far from being a ‘ghetto’: it was here that Jewish culture was shared with ‘buyers of every sect’. Unusually for a Victorian novelist, he regarded London’s multiculturalism as an asset to be prized.

Petticoat Lane, 2015.

Zangwill also broke new ground in depicting the diversity of contemporary Jewish life. Although it would have been easier to advocate for Jewish immigrants by representing them as a cohesive community with shared needs and aspirations, he instead drew the novel’s dramatic scenes from the conflicts of class, religion and generation that fissured it. He intended, he wrote, ‘to exhibit clearly that the Jew, like the Englishman, cannot be summed up in any single, or indeed in any score, of types’. Children of the Ghetto explores divisions among Jews who are wealthy and poor, orthodox and secular, immigrant and English-born, men and women, parents and children. This was a fractured, deracinated population – uncertain of its future, at a moment of critical change.

It’s this complexity that I want to convey in Zangwill’s Spitalfields, a smartphone app that uses Children of the Ghetto as the basis for a walking tour of the Spitalfields area. The app brings to life the dilemmas that beset immigrants and their children in the context of fierce debates about migration from more than a century ago. Like the novel, the app’s narrative follows the story of Esther, a London-born ‘grandchild of the ghetto’, her routes between soup kitchen and school, attic home and marketplace and her changing relationship to Spitalfields. Many of the sites where Zangwill stages the novel’s key scenes are still extant, offering a series of physical settings where the app augments extracts from the novel with related visual and aural materials from the period. And I’m able to use the unique capacity of mobile digital technology to immerse the listener in Spitalfields’ past while remaining attentive, or becoming more attentive, to its present, as you walk through a streetscape shaped by more recent histories of migration.

Perhaps the most remarkable fact about Children of the Ghetto is that it became a bestseller following its publication and was repeatedly reprinted for several decades. Written in the context of widespread confusion about immigration, the novel opened up a little-known world to the reading public. But Victorian readers found more than novelty in its pages: they also encountered the story of a daughter rebelling against her father’s authority, a father striving to understand his son’s lack of interest in his family’s traditions, a woman longing for the warmth and security of her childhood home. Readers discovered that the struggles of Jewish immigrants in Victorian London were not so different from their own.

Nadia Valman is Reader in English Literature at Queen Mary, University of London. She researches and teaches the literature of east London, where she also leads guided walks. She wrote and curated the free downloadable smartphone app Zangwill’s Spitalfields.

[…] West looks a lot like mid-19th Century. Regardless, it’s perhaps easiest to think of it as a magic-touched Victorian England and just move […]