A whistle-stop tour of migration in museums and galleries across the world

We have long admired the work and the writing of Eithne Nightingale, whose blog Chirps from around the World is a wonderful record of her travels and her reflections on migration. Here, Eithne takes time off from her research into child migration (as part of a collaborative doctoral award between Queen Mary University of London and V&A Museum of Childhood) to give a brief account of her observations on migration in museums and galleries across the world.

Over the last two years I have been visiting public spaces that explore migration – museums, galleries and others – in Europe, Australasia and South America. Over that same period the present, unfolding migration crisis has invoked in me a sense of paralysis. What possible role can museums and galleries play that is anything other than peripheral in the present context? Where is the evidence that they can contribute to a more tolerant and just society?

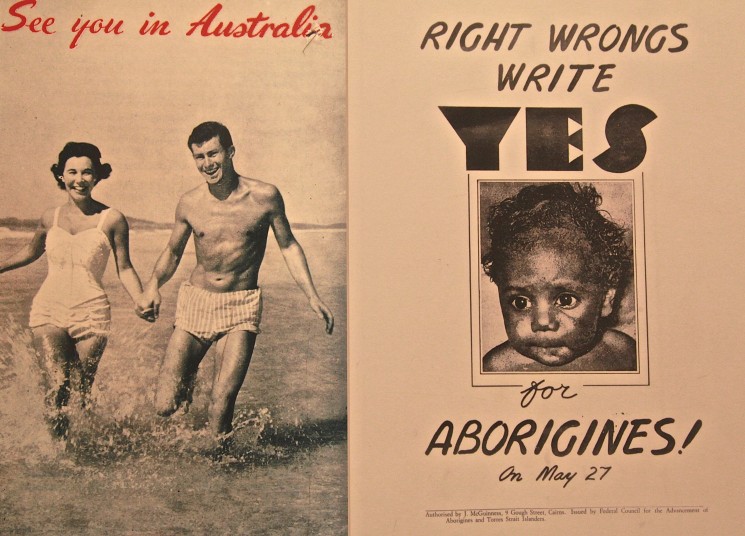

It is clear that museums across the world differ in their decision on whose histories of migration to include. The Immigration Museum in Melbourne and the Migration Museum in Adelaide, for example, explore not only the story of immigration to Australia but also its devastating impact on the indigenous communities.

Images from the 1960s in the timeline in the Immigration Museum, Melbourne. The image on the right refers to a referendum in 1967, which voted overwhelmingly for Aboriginal people to be governed by federal legislation and included in the Australian Census.

An impressive number of museums in Italy are dedicated to the country’s long history of emigration. But 1973 was a turning point: in that year more people migrated to Italy than left it. In a laudable attempt to encourage the visitor to see parallels between past emigrants and more recent immigrants, Italian museums have included sections on post-1973 immigration. That raises other questions, though: wasn’t there immigration to Italy before 1973? And wouldn’t a more intertwined approach have been better?

The Museum of Copenhagen recently put on a temporary exhibition, Becoming a Copenhager. They were keen to adopt an inclusive approach and so included people who had migrated from the countryside to the city as well as those who had come from abroad. But, in reality, how parallel or different are these experiences?

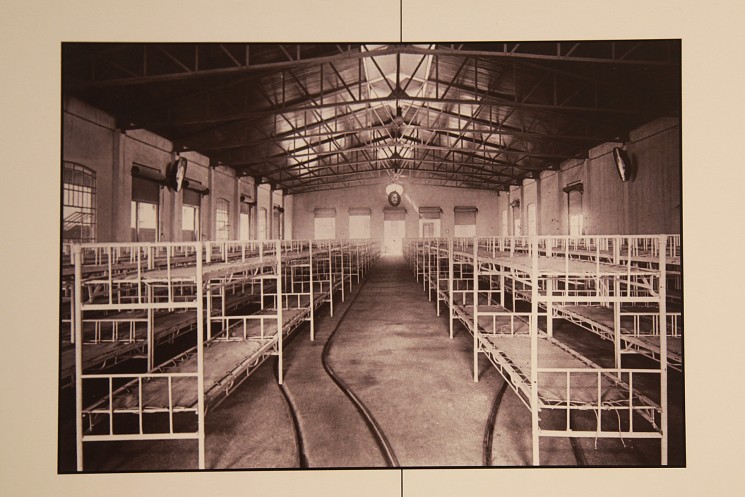

What, too, about forced migration? The Museu de Imigração in São Paulo touches on slavery, a small museum in Farum outside Copenhagen on trafficked women, and the Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney explores the convict experience.

Rooms where convicts slept in Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney.

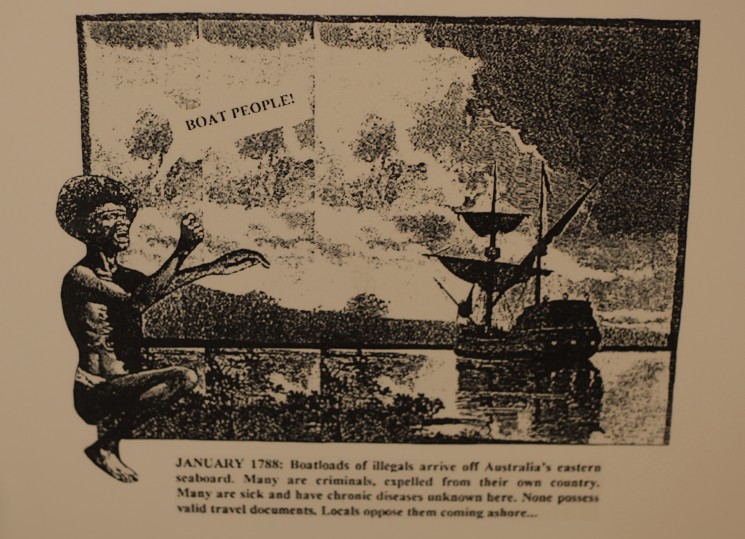

The Migration Museum in Adelaide questions our use of language about who is a ‘settler’ and who is an ‘immigrant’ – a clever cartoon underlines this dilemma: an aborigine looks out at a ship carrying ‘illegal immigrants’.

Cartoon about Aborigines being horrified at the arrival of illegals, Migration Museum, Adelaide.

And what about the diversity of the immigration experience – of children, of women, of those who can afford to travel first class, or of those who risk their lives on an open boat or under the carriage of a truck? Or of those people (and who cannot be struck by such stories?) struggling to Europe in wheelchairs?

Timelines in museums intrigue me. I have followed them up stairs, on gallery floors, along perspective panels and on inter-actives. The Museu de Imigração, São Paolo refers to pre-history and the very first movements of people to South America. The timeline at the Cité National de l’Histoire de l’Immigration in Paris starts in 1831 and ends in 2007. The occupation of the museum for four months in 2010 to speed up the regularisation of people ‘sans-papiers’ following legislation in June of that year does not feature here.

Time line in Hotel de Immigrantes, Buenos Aires.

A sense of place can be very evocative – to stand under a shower in the same building from which people left Antwerp for the New World between 1873 and 1934; to wait on a railway station in Dudelange, Luxembourg, where Italians arrived to work in the steelworks at the end of the 19th century; to walk between the beds in the dormitories in the Museu de Imigração, São Paolo, where, from the end of the 19th century to well into the 20th century, migrants spent their first few days in Brazil. In Hotel de Immigrantes, Buenos Aires, you can still see the footmarks and the fingerprints of those who arrived from Europe, exhausted after weeks at sea. The FHXB Museum in an old factory in East Kreusberg in Berlin shows how migration to both West and East Berlin has shaped and regenerated the area around the museum.

Photo of original dormitories in the Hotel de Immigrantes, Buenos Aires, and (below) the museum’s recreated bedroom, using mirrors.

I’m fascinated by how museums recreate migration scenarios. In the German Emigration Centre, Bremerhaven, clothed mannequins, speaking different languages activated by a visitor card, stand beside a swaying liner on a recreated quay; the 1970s’ shopping complex, focusing on immigration to Germany, works less well. Perhaps such scenarios, verging on the theme park, are more acceptable the more distant they are in history? The closer they get to us the more difficult their recreation is. Would we, for example, recreate the ships currently crossing the Mediterranean to reach Europe? Or is this an area that contemporary art – as in the work of Ai Weiwei – is perhaps more effective in modelling?

I’m fascinated by how museums recreate migration scenarios. In the German Emigration Centre, Bremerhaven, clothed mannequins, speaking different languages activated by a visitor card, stand beside a swaying liner on a recreated quay; the 1970s’ shopping complex, focusing on immigration to Germany, works less well. Perhaps such scenarios, verging on the theme park, are more acceptable the more distant they are in history? The closer they get to us the more difficult their recreation is. Would we, for example, recreate the ships currently crossing the Mediterranean to reach Europe? Or is this an area that contemporary art – as in the work of Ai Weiwei – is perhaps more effective in modelling?

Quayside with emigrants waiting to board for the New World in the German Emigration Centre, Bremerhaven.

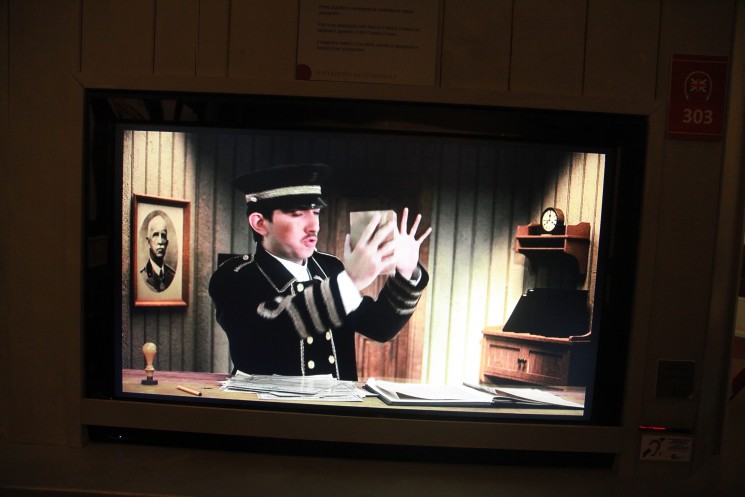

In several museums I took on the role of immigrant. At the Maritime Museum in Genoa I collected a passport and was quizzed by an interactive immigration officer before I embarked on the boat. When I got to Ellis Island, I was quizzed again – about money, health, political beliefs and disability. In Bremerhaven I followed in the steps of Mai Phuong from Vietnam who migrated to the former East Germany on a work voucher. In Melbourne I was put in the position of being an immigration officer and challenged into thinking what I would do when a man is aggressive towards a migrant on a bus.

Interactive of emigration officer in the port of Genoa in the Maritime Museum, Genoa.

Some objects have a particular power. Perhaps most powerful of all are the objects collected by Askavusa Collettivo (Barefoot Collective) in Lampedusa – weather-beaten wooden planks taken from abandoned boats, and migrants’ personal belongings displayed in an old fishing storage area without labels: “We can’t speak for the migrants.”

Migrants’ objects retrieved from the Wasteland in Lampedusa.

Letters too – such as personal pleas from Afghani refugees in one of the detention camps in Australia – can be powerful. Newspapers are useful in showing how debates over immigration have changed little over the decades. Personal stories can be very compelling, too, whether it is the story of the £10 English Pom or the child soldier to Australia, of the first migrant from Morocco to Antwerp or the child who was turned away from Ellis Island because of trachoma. Alongside the many stories of migrants who have been successful and contributed to the countries they have adopted there are difficult histories, too – like the stories of those at the Ballinstadt Emigration Museum in Hamburg who entered crime or who were turned away from the New World for pimping.

I have seen some impressive works of contemporary art – in Buenos Aires a piano that the owner brought from Europe creaks and groans, evoking the rough sea. In Mother Tongue by Zineb Sedira I watch the artist’s daughter, who speaks English, struggle to communicate with her grandmother, who speaks only Arabic.

Contemporary art, Migraciones en el Arte Contemporaneo in Buenos Aires.

I have been impressed by some genuine examples of co-production with refugee and migrant communities. Young refugees at Te Papa in New Zealand developed an exhibition based on their experiences in the Mixing Room – a flexible community space. At MAS in Antwerp, local volunteers or ‘trackers’ were given freedom to research stories about local communities. The research led to the exhibition 50 Years of Migration from Morocco and Turkey.

Exhibition co-curated with young refugees in the Mixing Room gallery in Te Papa Museum, Wellington, New Zealand.

The lessons I learnt from this whistle-stop tour are too many and too difficult to summarise within a blog such as this so I will attempt to do so, instead, in a future blog. Two things occur to me immediately, though. I believe that in any museum discussion or recreation of migration it is important to be clear about objectives and to measure progress and performance against these. And, further, we need to be brave, take risks, be creative, open up space for genuine dialogue with all sectors of the population, collaborate closely and equitably with migrant communities and, like the Askavusa Collettivo on Lampedusa, engage in whatever way we can with the present crisis.

For more information on the museums Eithne has visited, please visit her website.

And read more about her research into child migration as part of her Collaborative Doctoral Award between Queen Mary University of London and V&A Museum of Childhood here.