Archives

28 May, 2019

Belén L.Yáñez is the last artist in residence in the art studio at the Room to Breathe exhibition. It has been exciting to see this space filled with so many different artistic practices and to witness how visitors have responded to them. Belén comes from Galicia, a land of migrant people or, as she calls it, of explorers. Her desire for travel, adventure and different life experiences is the main trigger of her migration story: from Santiago de Compostela to Budapest and Madrid, then to Sicily – where she worked with the National Institute of Ancient Drama – Belén developed her artistic career in the places she lived in. Although acting and theatre were her point of access to the world of art, performance became her main focus, especially after she moved to London to study Contemporary Performance Practices. Belén’s body of work is a reflection of her political understanding of both the social world and human relations. Her work, however, is also a result of the very rich experiences she lived through migration.

As with previous artists in residence we are going to learn more about Belén L.Yáñez through a series of questions and answers. Dima Karout, curator of the art studio, will offer her thoughts on Belén’s work, together with comments from previous artists in residence.

Assunta Nicolini (AN): Belén, welcome to the art studio at Room to Breathe. Your personal life/migration journey from Galicia (in north-west Spain) to London, with several detours along the way, has defined your artistic career. To what extent do you consider mobility essential to your work?

Belén L.Yáñez (BLY): The constant travelling brings new perspectives to my understanding of other people and the world we live in, and my art is a reflection of this. Being in movement is being alive. I have embraced my constant travelling as an essential part of my development as an artist. Therefore, my journey has become my art.

AN: Among the range of artistic practices you engage with, collages take a particular space in the art studio at the Migration Museum, where you both display your work and invite visitors to make their own. Could you tell us which process you follow when making your collages? Do you engage visitors in the same creation process that you go through?

BLY: I use collage as the medium to represent my perceptions, because collages are a composition of layers in which new images are created through the transformation of existing ones, in the same way that perception is transformed by being received by the senses and interpreted differently by different people.

My collages are an open door to all possibilities, a process of freedom that allows me to deconstruct reality by playing within layers of imagination, and to open up new perceptions using the ideas hidden in my subconscious.

In my studio, I created a space in which visitors are invited to explore, connect with other people and experience things.

Belén L. Yáñez at work in her studio in the “Room to Breathe” exhibition at the Migration Museum.

AN: Performance art is an art practice that you came to later in your career as an artist, in particular since you moved to London. Could you tell us about your formative experiences and your vision for performance art?

BLY: My fields of expertise are strongly interdisciplinary and cross-cultural with an academic background including a postgraduate course (MA) in Contemporary Performance Practices from the University of East London, and an undergraduate BA (Hons) in Politics & International Relations from Santiago de Compostela University.

I understand performance as an act that occurs between the performer(s) and the audience in the present time. In general, in my work, I am interested in the live encounter between the audience and the performer, a creative co-production through which a live experience is created. For me, performance only exists as a ‘real’ encounter between audience and performer, and through the experience that takes place between them artwork is created.

My work is a hybrid practice that seeks new ways to engage audience members as active participants. I aim to encourage a critical consciousness to reflect on current social realities.

AN: Dima, as curator of the art studio what is your opinion of Belén’s work?

Dima Karout: Belén is an intriguing multi-disciplinary artist whose work reflects on social issues, human connections, migration and identity. Her residency brings an exciting dimension to the Migration Museum, where art leaves the walls, and acts in the space. In her participatory performances, she invites visitors to transform themselves into active participants so that their moving bodies become a core part of the final piece. She brilliantly blends the boundaries between the artist, the artwork and the viewer to propose a sense of entity in a final coherent piece. On first coming across her different performances, I really admired her ability to design a site-specific work to create a conversation not only with the participant, but also with the history of the place.

What has most inspired me is Belén’s understanding of space and how she navigates her concepts through various mediums and spaces: from composing elements into the emptiness of a white page in her collage pieces – ‘a medium that allows me to rebuild a new reality, create new narratives by playing with layers of imagination’ – to designing a conceptual performance in which the body experiments and moves in the physical space. ‘Awakening invites participants to play different social scenarios and reflect on their culturally learnt behaviours.’

When I first met Belén, I was very impressed by her positive energy, body language and how in harmony she is with the work she creates. It is very refreshing to see how true she is as an artist to her practice. I always describe Belen as a travelling sun: she crossed borders, collected experiences, moments and light and she shares all of this with us through her art. Belén transformed the art studio space into not only a room to breathe, but also a colourful room full of movement and life. She offers a space for our imagination to travel freely and invites ‘all senses to a total awakening’.

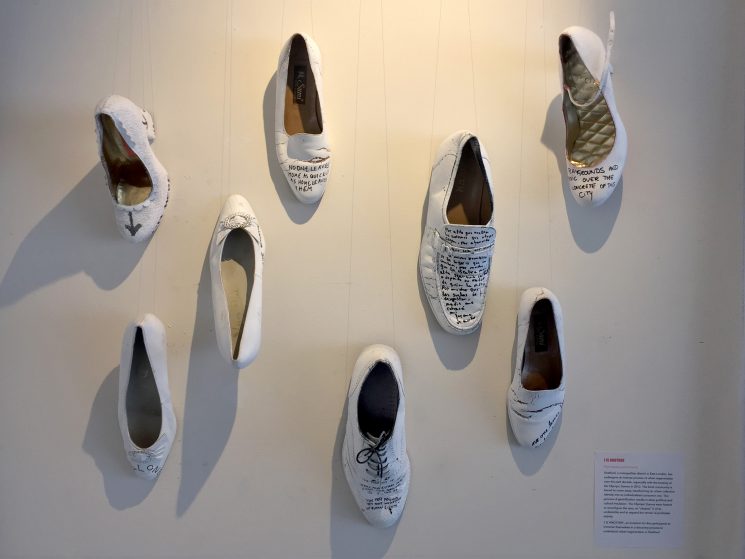

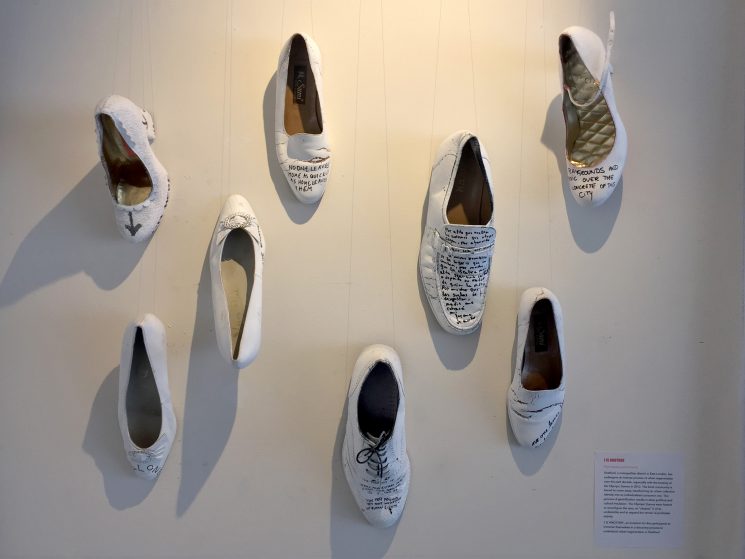

When I stepped into Belén’s art studio, I immediately connected with the strong presence of orchestrated movements, and sensed the importance of the body in all of her work. In her collage pieces, your eye follows the visual flow she composed and the fragmented images of parts of the human body. And there are various elements delicately suspended in every corner or hung on the walls in unusual ways, all related to her previous performances. The presence of elements such as white shoes covered with handwritten lines of text, transparent clothes, and colourful handmade masks, all suggest the absence of the body, but also that there is a performance waiting to happen – a performance that becomes complete with the human. With you. I strongly invite you to visit Belén’s studio, to discover her unique universe, and to experience her powerful art.

AN: Ceyda and Shorsh, as previous artists in residence at Room to Breathe, which work by Belén would you consider your favourite?

Ceyda Oskay: I Is Another reminds me of my work with felt insoles for shoes, on which I embroidered ‘Come’ and ‘Go’ – gel-git – which is a phrase in Turkish that means both ‘tides in the sea’ and ‘indecision’. I liked seeing how different symbols, in this case shoes, can mean completely different things in artwork.

“I Is Another”, a participatory performance, invites participants to immerse themselves in a discovery process to understand urban regeneration in Stratford (east London).

‘Try walking in my shoes . . . ,’* Belén seems to be saying in this artwork – or at least try listening to others’ stories . . .

Belén’s piece is about gentrification but, rather than indulging in nostalgia, she employs an active ‘present’ participatory act, or perhaps performance: she asks participants to wear one of the shoes she has prepared, and to walk through neighbourhoods undergoing the social transformation of gentrification.

*lyrics to Depeche Mode’s ‘Try Walking in my Shoes’ song

Shorsh Saleh: Belén’s miniature collages are full of unexpected and surreal images. I found Watering Memories very interesting. The work is divided into two sections: in the top part we see the silhouette of a man, holding a watering can, set against a calm and empty background; the bottom part is completely different, with lots of lines crossing and fragmented words and images, all of which creates the overall effect of a graveyard. Underneath the crossing lines there is an image of an upside-down tree without any leaves, creating the effect of tree roots. Once you see the tree, you associate it with the person holding the watering can. In my opinion, the relation between the man and the tree is the key to understanding the message behind the work: the connection between you and your roots and your memories. This work is deep and sad and taps into the hidden melancholic feelings inside us all.

“Watering Memories” by Belén L.Yáñez, an analogue collage based on an old-fashioned picture postcard.

Belén L.Yáñez is artist in residence from 30 April to 2 June 2019. Belén will be in her studio most days until the end of her residency, and you can stop by to chat with her, and design your own artwork. She is also running two film installations this coming weekend, on Saturday 1 June and Sunday 2 June.

Assunta Nicolini, gallery supervisor, has been curating blogs about the artists who have had a residency in the gallery.

Dima Karout is a visual artist and educator and is curator in residence of the art studio inside Room to Breathe.

View the full schedule of artists in residence and find out more about Room to Breathe.

16 April, 2019

In April we welcome a new artist in residence to Room to Breathe: the multimedia artist Shorsh Saleh. Shorsh’s display in the art studio inside the exhibition reveals a range of delightful artistic practices, from miniature paintings, installations to carpet weaving. His body of work reflects his layered and complex identity both as an individual and as an artist. Coming from Iraqi Kurdistan, Shorsh found his life intrinsically entwined, first and foremost, with the geopolitics of his land and the collective resistance struggle of Kurdish people in Iraq. Armed conflict, persecution, displacement and migration are all part of his lived experience.

As with previous artists in residence we are going to discover more about Shorsh Saleh’s artistic practices and their relation to migration with a series of questions and answers. In the final questions we ask Dima Karout, curator-in-residence of the art studio, and two other artists in residence for their reflections on Shorsh’s work.

Shorsh Saleh leading a workshop in his studio in Room to Breathe at the Migration Museum © Migration Museum

Assunta Nicolini (AN): Shorsh, welcome to the art studio inside Room to Breathe. As an artist who is Kurdish and migrant – how do you express and reconcile the complexity of multiple identifiers?

Shorsh Saleh (SS): For me these aspects of my identity work in perfect harmony and enrich my life. All of these areas of my identity are expressed through my art.

AN: Your journey as artist starts at home, by which I mean not only the Middle East and Iraqi Kurdistan but also your family. Could you tell us about your early artistic formative years?

SS: There was no formal art education during my school years but I come from an educated family and I was introduced to art at an early age by my older brother. I continued to educate myself through books, teaching myself weaving, carving, painting and drawing. I also taught myself philosophy, art history and art theory. I participated in many exhibitions in Kurdistan before coming to the UK.

AN: Your experience of arrival and settlement in the UK is shaped both by a lengthy, bureaucratic process to gain refugee status (eight years in total) and by accessing educational institutions where you could develop and expand your art techniques. How would you describe such an experience?

SS: The experience of waiting for eight years for my asylum case to be granted was very challenging. During that time I continued to develop my art and I worked as a volunteer, leading art workshops for refugees.

Once my asylum status was accepted, I began an MA in Traditional Arts at the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts in London. The MA involved learning twelve techniques of traditional art such as geometry, icon painting, stained glass, ceramics, miniature painting, gilding, wood parquetry, etc. I focused on carpet weaving and design for my final degree show and was lucky enough to sell my degree-show carpet to HRH Prince Charles, and it is now at Balmoral Castle. I now teach at the school.

AN: Miniature paintings and carpet weaving are two of your principal art forms. Why do you particularly connect with these? And how do you expect to connect to the public through these?

SS: In the Middle East carpets have always been seen as the highest of art forms. Miniature painting is also imbedded in Middle Eastern culture, having originated in Iraq and Iran as a form of decoration to illustrate texts. Both carpet weaving and miniature painting are ancient forms of communication and artistic expression which are widely appreciated in both the Middle East and the Western world. I often use carpet motifs in my miniature paintings to express my identity through my own language and to connect and communicate with viewers, both Middle Eastern and Western. My works combine these traditional techniques with contemporary issues relating to migration, identity and Kurdish politics.

AN: What are you expecting from your residency at the Migration Museum?

SS: I hope to give visitors to the museum an insight into my working practices and culture. I look forward to sharing and discussing my work with the public and to creating some new work.

AN: Dima, as curator in residence of the art studio inside Room to Breathe, what reflections could you offer on Shorsh Saleh’s work?

Dima Karout: I have a great admiration for Shorsh’s work and his ability to transform fragments of his unique journey into pieces of art that brilliantly communicate intimacy, fragility and resilience.

I first read Shorsh’s portfolio and was immediately moved by his talent and his courage. Through his art and the subjects he reflects on, I sensed a human who was able to transform the ugliness of conflicts into engaging and communicative art. I discovered an artist who creates using various mediums and who can easily navigate his hands and mind between traditional skills and modern design. And later, I met him. And it is hard not to be impressed how an artist like him was able to express through his work the difficult path and different struggles that emerge from forced displacement and the long quest for safety and a place to call home.

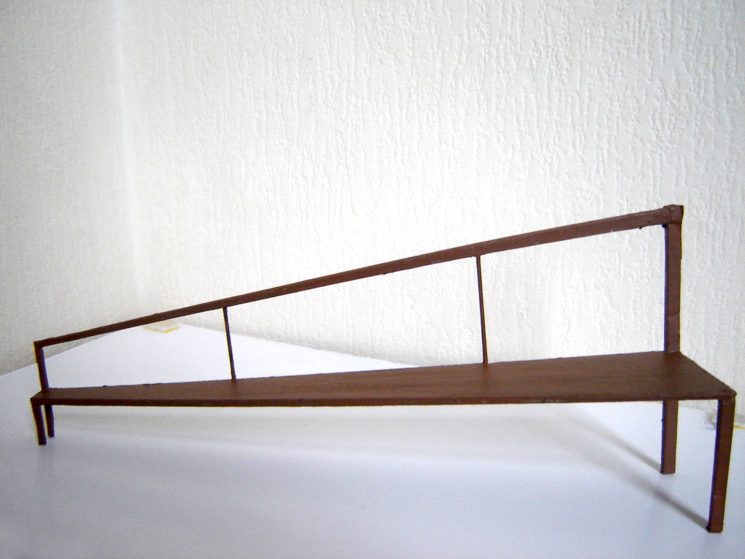

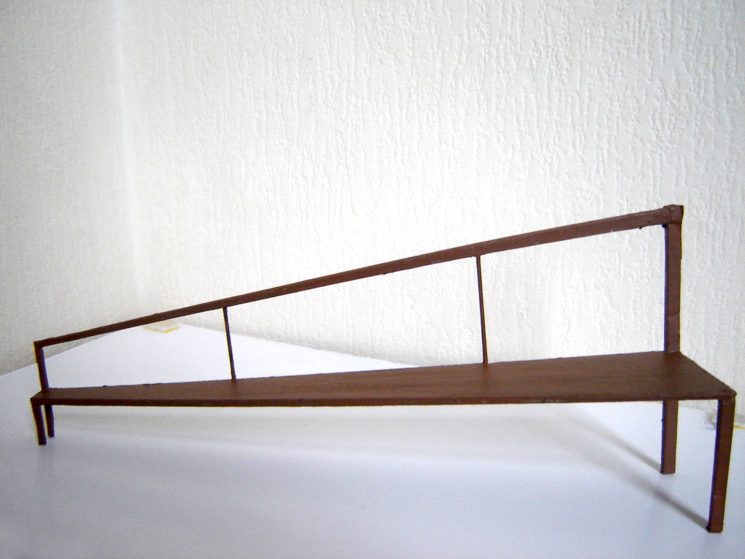

“Waiting for asylum II”, wooden model for sculpture, 20 x 40 x 10cm, 2009. © Shorsh Saleh

There is a lot to express once you step into Shorsh’s space at the Migration Museum. A wave of peace enveloped me while navigating the walls of his art studio. Discovering his precious art pieces gave me a sense of understanding of all the inspiring places an artist’s journey can take us to. And how important for all of us to be there, to listen with our hearts, to step out of our comfort zone, and to understand a wider picture.

“Waiting for asylum III”, wooden model for sculpture, 20 x 40 x 10cm, 2009. © Shorsh Saleh

I was particularly touched by Waiting, a series of models for sculptures Shorsh sent in with his application to be the artist in residence in Room to Breathe, and which he later presented another version of in his art studio. Shorsh wrote that Waiting represents his experience of waiting eight years in the UK system for his application to be heard while “my life was on hold and I was unable to work or to travel”. I found this artwork very powerful because every one of us can connect with it in our own way. Any human who has crossed a border has experienced this state to a certain degree. But I believe Shorsh’s depiction of this experience takes it to a different level. You can read the work from left to right or from right to left. I read them as the chairs sinking into the ground, reflecting the person sitting on them who is waiting endlessly to start a new life. Later, when I spoke to Shorsh, I had a glimpse into when this artwork was created; as with most of his work, he was sketching them alongside his dreams without knowing whether he would be able to create them in full scale one day. I was touched by how an artist and his artwork share the same journey and are both ‘waiting’ to exist in full.

I am very humbled and inspired to have Shorsh with us at the Migration Museum; it’s a great chance for all of us to cross paths with him and discover his powerful work and journey. I believe all visitors will have a special experience uncovering how a remarkable artist like him kept his soul alive, kept his culture alive, and created beauty out of unimaginable conditions, and chose to generously share his knowledge and art with all of us.

AN: Ceyda, as the most recent artist in residence, and Belen as the final one, how do you connect with Shorsh’s work? What are your favourite works among those displayed in the art studio?

Ceyda Oskay: I found Shorsh’s wire ceramic piece The Border very powerful. Shorsh placed barbed wire on a ceramics tile, and allowed it to melt, transforming it into something beautiful and magical and yet also leaving a slightly haunting trace of what it was. The viewer is not told where the wire is from, and is left to wonder “Which boundary? Which border?” – and in this wondering the viewer is reminded of just how many boundaries exist in the world.

“The Border”, ceramic tile, glaze and barbed wire, 15×15 cm, 2018 © Shorsh Saleh

In transforming it into a tile, Shorsh alludes to multiples: perhaps many tiles will be made from this one, and form a different type of boundary, a wall. In multiplying, the object may also lose its power, becoming one of many lines.

Belén Y Yáñez: When I saw Aftermath for the first time, I found an immense ocean in front of my eyes, a colourful boat that drifts with an unknown destination, a little boy laid down in a new land. A visual metaphor of life itself.

I also discovered in Aftermath an invitation to get lost in the waters of the ocean, which seem to me a dark blue, almost black, colour …

“Aftermath” – natural pigment and paper boat on paper. © Shorsh Saleh

After some conversations, I realised that what was in front of my eyes was a faithful representation of a real story, the journey of Aylan, a three-year-old Syrian boy whose dead body was found washed up on a Turkish beach. Aylan was drowned, like thousands of others who were fleeing suffering in their homelands, attempting to reach an unknown land in which to rebuild their lives.

Aftermath is a mirror reflecting the story of too many refugees and migrants who die while trying to reach another opportunity. Aftermath is an alarm that has not stopped ringing since Europe began to experience what is called the ‘migratory crisis’. Aftermath is a shout that calls for a change in migration policies now.

Shorsh Saleh is artist in residence from 4–28 April 2019. Shorsh will be in his studio between 3pm and 5pm every Saturday during his residency, when you can stop by to chat with him, and design your own flying carpet. He is also running two flying carpet weaving workshops – on Sunday 14 April and Saturday 27 April (both are now sold out).

Assunta Nicolini, gallery supervisor, is curating further blogs about the next artists who are due to have a residency in the gallery.

Dima Karout is a visual artist and educator and is curator in residence of the art studio inside Room to Breathe.

View the full schedule of artists in residence and find out more about Room to Breathe

14 March, 2019

Ceyda Oskay is the new artist in residence in our current exhibition, Room to Breathe. As with previous artists, we asked Ceyda and the curator in residence of the art studio, Dima Karout, a series of questions and answers to find out more about Ceyda’s artistic practice.

Ceyda uses textiles to explore symbolic themes around migration experiences, inviting us to engage with more abstract concepts and reminding us that individual migration projects are shaped by more than the structural dimensions of poverty or conflict. Her interest revolves around the exploration of dreams, utopias, dystopias in migration experiences, and her artistic practice features a unique use of textiles, imprints and interactive spaces.

Ceyda is also offering visitors the chance to participate in workshops where they can learn about, and contribute to the making of, a wide range of objects and artworks.

Ceyda Oskay’s studio in “Room to Breathe” © Migration Museum

Assunta Nicolini (AN): Textiles are the dominant medium in your artistic practice, especially your work currently on display at the Migration Museum – why textiles in particular?

Ceyda Oskay (CO): I’ve always been interested in textiles. My mother and grandmother taught me different textile techniques in Turkey and I remember making clothes for my Barbie dolls. Growing up in Saudi Arabia, part of the Silk Road, I remember going to fabric markets with my mother, where there would be textiles from all around the world. I loved textiles for their diversity and expressiveness. It always felt very natural for me to use textiles to express myself or my ideas with.

Additionally, socially, textiles have been very important in world history from the trade in natural dyes and the social status of Tyrian purple for royalty, the trade in indigo and its transformative effect on farms in India, to textile weaving and the British industrial revolution.

Having moved around a lot, I have always been interested in the versatility of textiles, and the way they can so easily be transported. I am also interested in, and I’m co-writing a chapter on, Sadu weaving – which is the nomadic weaving used to make tents and bags in the Arabian peninsula and beyond. There, the textiles form a home.

Additionally, textiles themselves are transformative – they can be changed into another item just by altering the way they are sewn and put together. They are easy to experiment with and I like experimentation in my work. I like the versatility and expression textiles offer, and their universality.

A doodle blanket, 2018 © Ceyda Oskay

AN: To what extent has your lived experience as a migrant and a practitioner working with migrants and refugees around the world shaped your artistic and conceptual work? And how did you develop your interest in ideas of utopia, dystopia and dream in migration contexts?

CO: Interesting question – because for many years as a practitioner, I couldn’t make art in the traditional sense. I started to move away from art as an object, or even installation, and towards art as an experience.

I was interested in migration and war as memory, having done humanitarian work in relation to Syria and Iraq – but, rather than preserving this memory in an object, I’m more interested in creating new and diverse experiences between people that transform them and create the hope of something better.

I’m really interested in the work of the Artist Placement Group (APG), which embeds artists in institutions – and in work like Francis Alÿs’s paint can, where he pours a thin line of paint along an international border.

In terms of dreams, I’m currently trying to make person-specific sleepwear and sleeping bags: the blue Cyanotypes were going to be transformed into sleep clothes, and I’m collecting images from friends that are of a place that inspires or calms them . . . I’m collecting sound recordings of lullabies in different languages, and trying to put that together with creating sleeping bags. It’s a way of bringing object, travel, experience and interactivity together. I’d love it if visitors contributed lullabies, or took part in the dream-clothes somehow.

AN: Dima, as curator in residence of the art studio inside Room to Breathe, could you tell us how and why you selected Ceyda’s work and how it relates to the other upcoming artists in residence?

Dima Karout: When I was invited to curate the art studio space, the first thing I proposed was to take a democratic approach and to launch an open call allowing us to reach migrant artists based in London and working on themes related to resilience through art.

We offered residencies to Ceyda Oskay, Shorsh Saleh and Belen L Yañez, three artists with a body of work inspired by their personal journey and human connections – artists who are generous, able to share their knowledge and creative process, and willing to include visitors in a participatory practice.

I was touched by Ceyda’s unique journey: travelling between countries, then landing in London with experiences related to different communities in which she had witnessed people’s stories and connection to their surroundings, and where she had created participatory art, and undertaken humanitarian work. I sensed that Ceyda’s presence at the Museum would provide visitors with an intimate experience and an elaborate understanding of the meaning of home and belonging.

When you step into Ceyda’s studio at the Migration Museum, you are immediately immersed in fragile stories assembled with a high level of sensitivity, intimate moments that she brilliantly re-created to communicate fragments of her journey. Ceyda created a dreamlike space for all of us to experience on our own: textile art filling the walls, a shell series presented in a corner, an open invitation to all visitors to share their lullabies, dreams and places. Through this experience visitors can engage in a wider conversation around the illusional borders that some of us have never visited and shake our perception about the meaning of a place.

“The Bosphorous between Asia and Europe – The seagull has migrated from Peru – The textiles look dream-like, reminding us of dreams and places we go to in our dreams, and of utopias and dystopias” © Ceyda Oskay

A wall in Ceyda’s studio combines photos from the Bosphorus printed on fabrics using Cyanotype print technique. With its blue shades, the work brought the sky and the sea into my thoughts. And one of the photos in particular brought me to my own journey. I found myself glimpsing out of Ceyda’s window while juxtaposing my own hometown over her landscape – I floated to Damascus creating an assemblage of its building as if I were standing there in the comfort of my distant home.

Ceyda’s work is powerful. It took me and museum visitors on a textural and pictorial journey full of fragility, humanity, dreams and hope. And I am happy that with the museum team and visitors we were given the chance to discover and reflect on this influential work.

AN: Belen and Shorsh, as upcoming artists in residence, could you tell us how you relate to specific work by Ceyda?

Belen L Yañez: Ceyda’s piece “Hands on Subway/London Underground” instantly grabbed my attention. I am currently working on a piece called “Encounters”, in which I invite participants to establish a dialogue with each other using their hands to foster an empathic connection with people who may not share the same cultural background nor have the same physical appearance. Ceyda’s piece is composed of several copies of photos of the hands of immigrants and people travelling within London. Stopping for a minute and observing those hands is enough to allow you to read their meaning. It was wonderful to breathe the diversity of travellers who inhabit the London Underground, to imagine their stories and somehow to connect with them for a few minutes.

Hands on subway/London Underground of immigrants and people travelling within London © Ceyda Oskay

Shorsh Saleh: Ceyda printed oyster shells that she found on the Isle of Sheppey in the UK. The shells have images of military pillboxes falling over that look like homes; other shells have images of boats on them.

© Ceyda Oskay

As a migrant myself, Ceyda’s work spoke to me about journeys taken across seas in search of a new homeland. I felt a connection to the shell series she is presenting in her art studio. The ethereal imagery of boats and seascapes symbolises to me the difficulty of journeys, all contained within a broken shell that had once been a safe home.

Ceyda Oskay is in Room to Breathe until Sunday 31 March and will be holding a pillow-making workshop on Saturday 23 March and a family T-shirt making workshop on Saturday 30 March. Tickets for both these workshops are available through Eventbrite. Assunta Nicolini, gallery supervisor, is curating further blogs about the next artists who are due to have a residency in the gallery (details are available on our exhibition page).

28 November, 2018

Room to Breathe at the Migration Museum takes visitors on an immersive journey through a series of interconnected rooms, revealing the multi-layered experience of migrants and refugees arriving in a new country. Intimate personal stories are brought to life through audio recordings of oral histories as visitors go through the different rooms. At the centre of the gallery is the ‘Room to Create’, a space conceived as an art studio, which will be occupied by a succession of artists, each on a monthly residency. These artists have been invited to make the studio their own, displaying previous art projects while creating new artwork.

The first artist in residence and the curator of this art studio is Dima Karout, a visual artist and art educator originally from Syria, but who has lived in several countries before arriving and settling in London. In her journey from Syria to Britain via France, California, and Quebec, art has been a constant source of reflection and engagement for Dima.

This blog has been written as a series of questions and answers, with Assunta Nicolini (gallery supervisor at the Migration Museum) asking the questions and Dima and Sue McAlpine, one of the Migration Museum’s curators, answering them.

Assunta: Dima, could you gives us some background to your collaboration with the Migration Museum in ‘Room to Breathe / Create’?

Dima: My appreciation of the Migration Museum goes back to when I moved to London and visited their previous exhibitions. The first time I stepped into the Museum, it all felt very familiar. Some of the elements they presented reminded me of my own work – the suspended canvas, the personal stories, and the collective truth. I loved the slogan ‘All Our Stories’, and its sense of inclusiveness. We’ve been in conversation ever since. I met Sophie first, the Museum’s director, then Sue, one of its curators, and I showed her some of my installation artwork. Both she and Sophie were very welcoming and positive. This current exhibition, Room to Breathe, was a perfect opportunity for us to collaborate. I was thrilled to be invited to be the artist and curator in residence for the exhibition, and to add my vision to this project by designing the concept and overseeing the art studio space and the residency programme.

A ‘room to breathe’ is a metaphor that relates to a lot in my life. My art studio gives me a peaceful space to reflect on conflicts bigger than me, and to create. And the museum curators were aware of the importance of art in a time of displacement, in an artist’s quest for identity and meaning, and in their life in general. This space, as we designed it, gives artists from migrant backgrounds a platform to share their work, interact with visitors and tell their story in their own way. It is a space for them to represent themselves: this was very important for me. We will welcome a new artist from a migrant background every month until June, when I will work with all the artists to curate a final group exhibition.

I am very excited about this collaboration and grateful to be working with socially engaged people. It is important (and visitors’ feedback and reactions confirm this) to change the narrative about Syrians, to work with them and present them in a different light – as artists, educators, travellers – and to show that there is more to a Syrian person than the ugliness of war. I am glad to be part of this process.

Assunta: As the first artist and also the curator in residence at Room to Breathe, what is your vision and approach for the Art Studio?

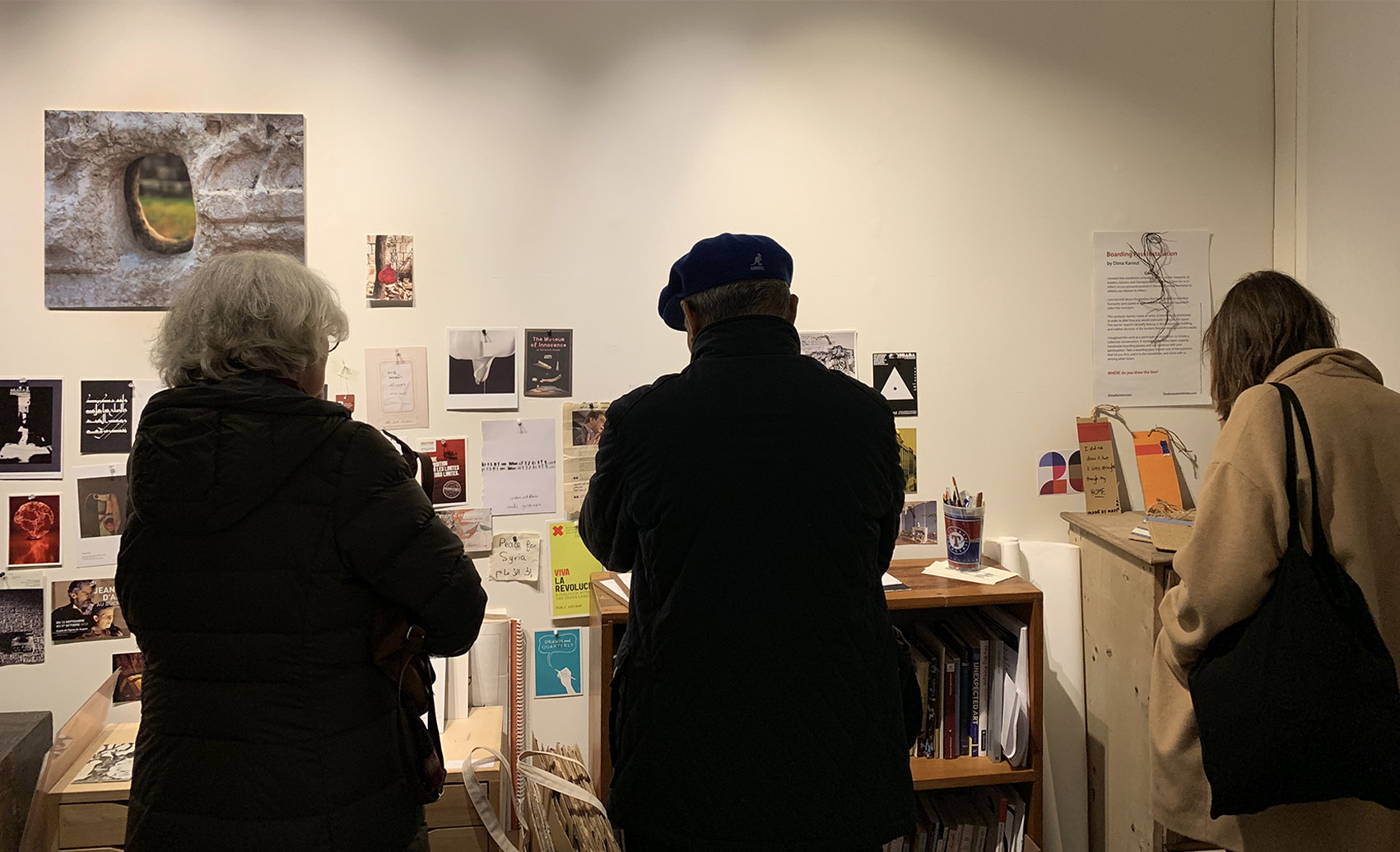

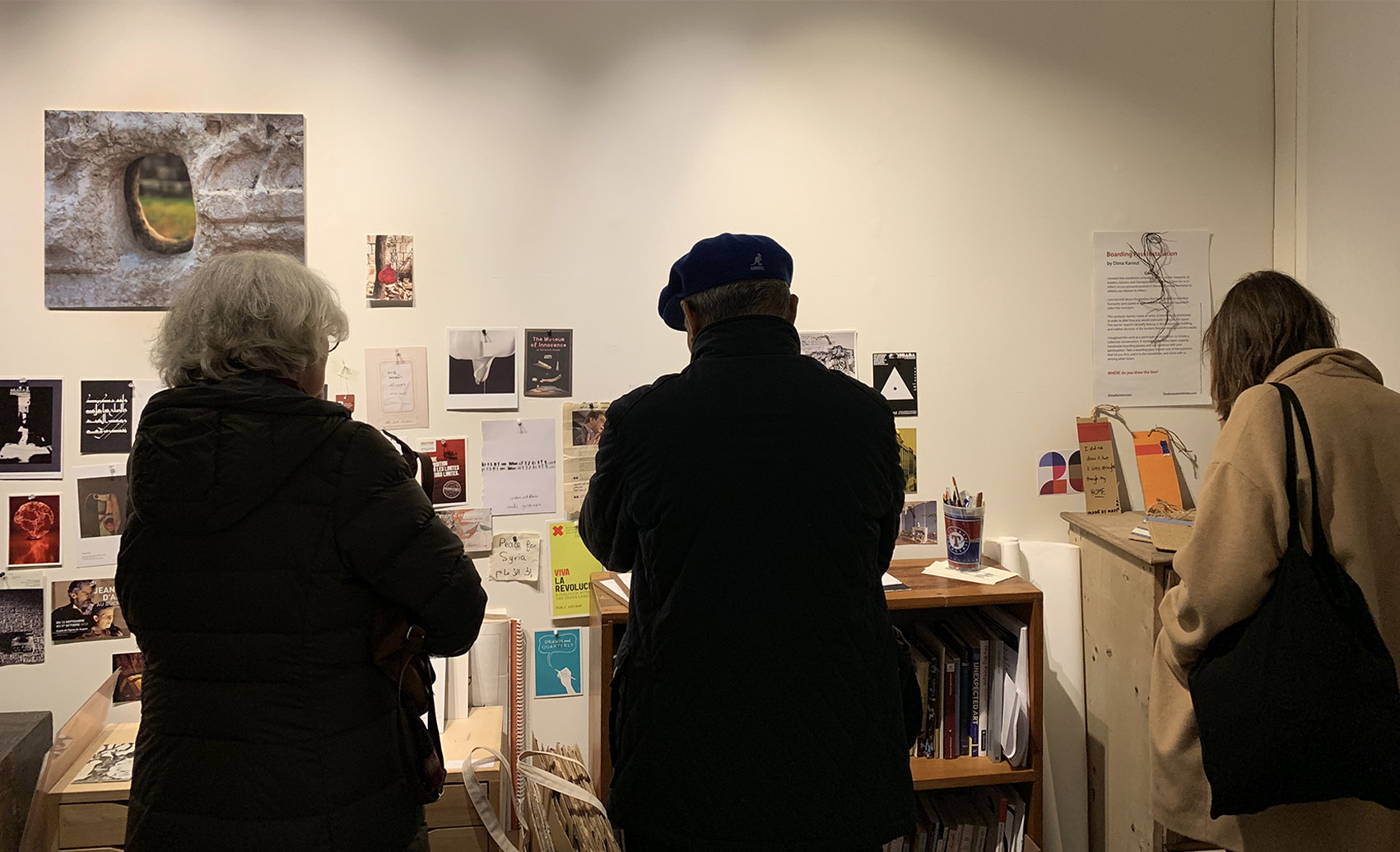

Dima: As a curator, I wanted the room to reflect an authentic art studio. The artists are invited to display their artwork, handwritten notes, their own books, art tools and materials, etc. The space is personal, intimate and true to the artist’s own life and practice. But most important for me was to fully respect the invited artists’ freedom and to allow them to decide for themselves what their room to breathe would look like. We selected these artists from an open call we launched online, and every month sees a new display of the work and universe of a talented migrant artist. It’s really exciting that it shows there isn’t one way to design this space.

During my residency as an artist, I share pieces from different projects I’ve worked on over the years and exhibited in Damascus, Leipzig, Paris, Montreal and London. Visitors can go on a journey with me, see a photo for a set I designed for The Shroud Maker, a play shown at RADA last May, read some of visitors’ contributions to my installation Boarding Pass at Shakespeare’s Globe last June, follow my travels by reading fragments of my Travelling Souls project, and get to know me better by browsing my books, learning about the friends, artists and writers who inspired me, etc.

Visitors discovering aspects of Dima’s journey in her art studio at the Migration Museum. The large photo on the left is “Hope in Damascus”. © Rudy Hajjar

In addition to all that, I am present in the space most of the time, interacting with visitors. I approached the art studio as an educational space that brings art closer to everyone. I offered hands-on art workshops, and free printing sessions and I designed a participatory installation in which visitors were invited to sit in the art studio on a large table equipped with tools and materials and to create a piece of art reflecting on Human Bridges, and add it to the growing installation.

Assunta: How have visitors reacted to your work and participatory installation at the Migration Museum?

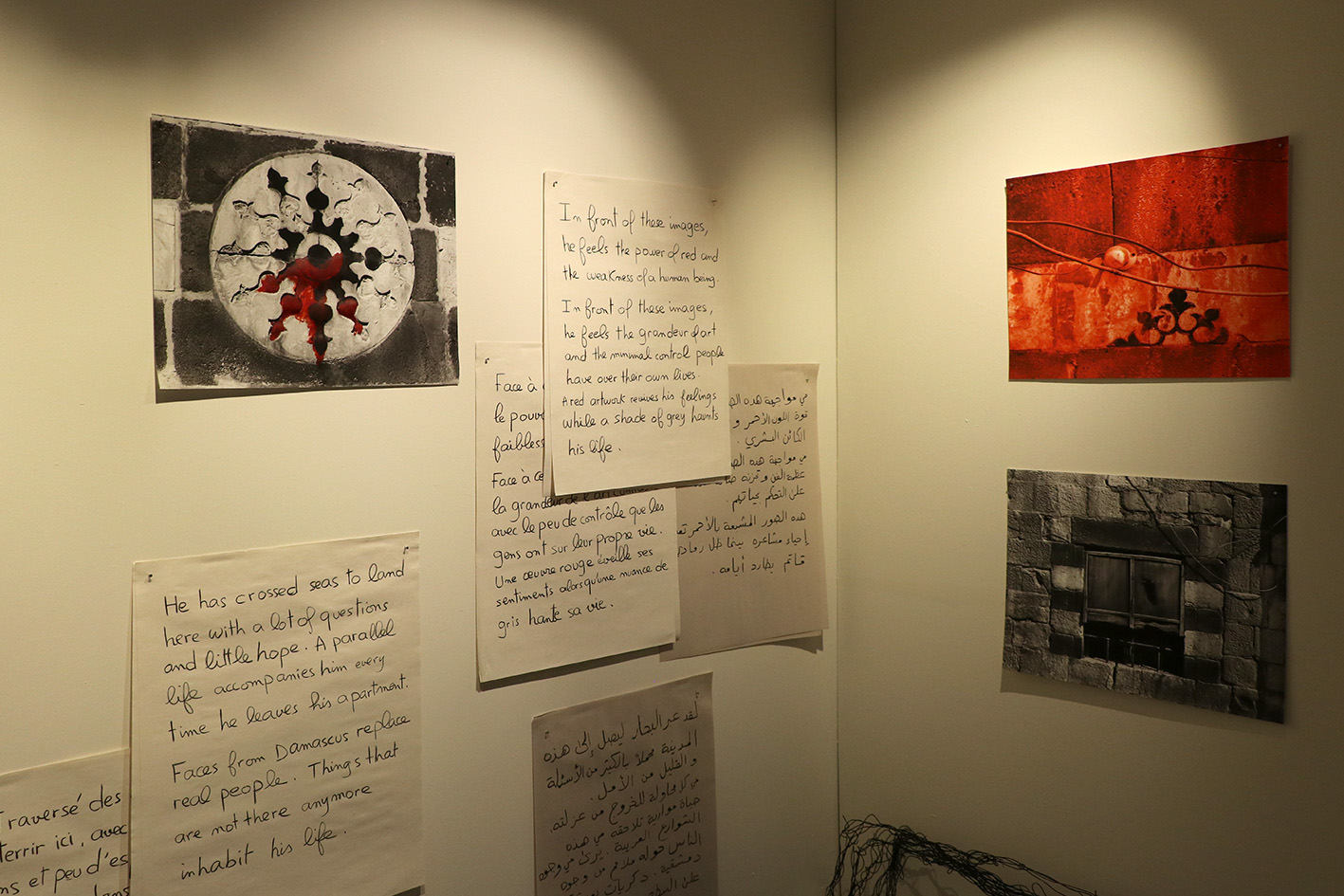

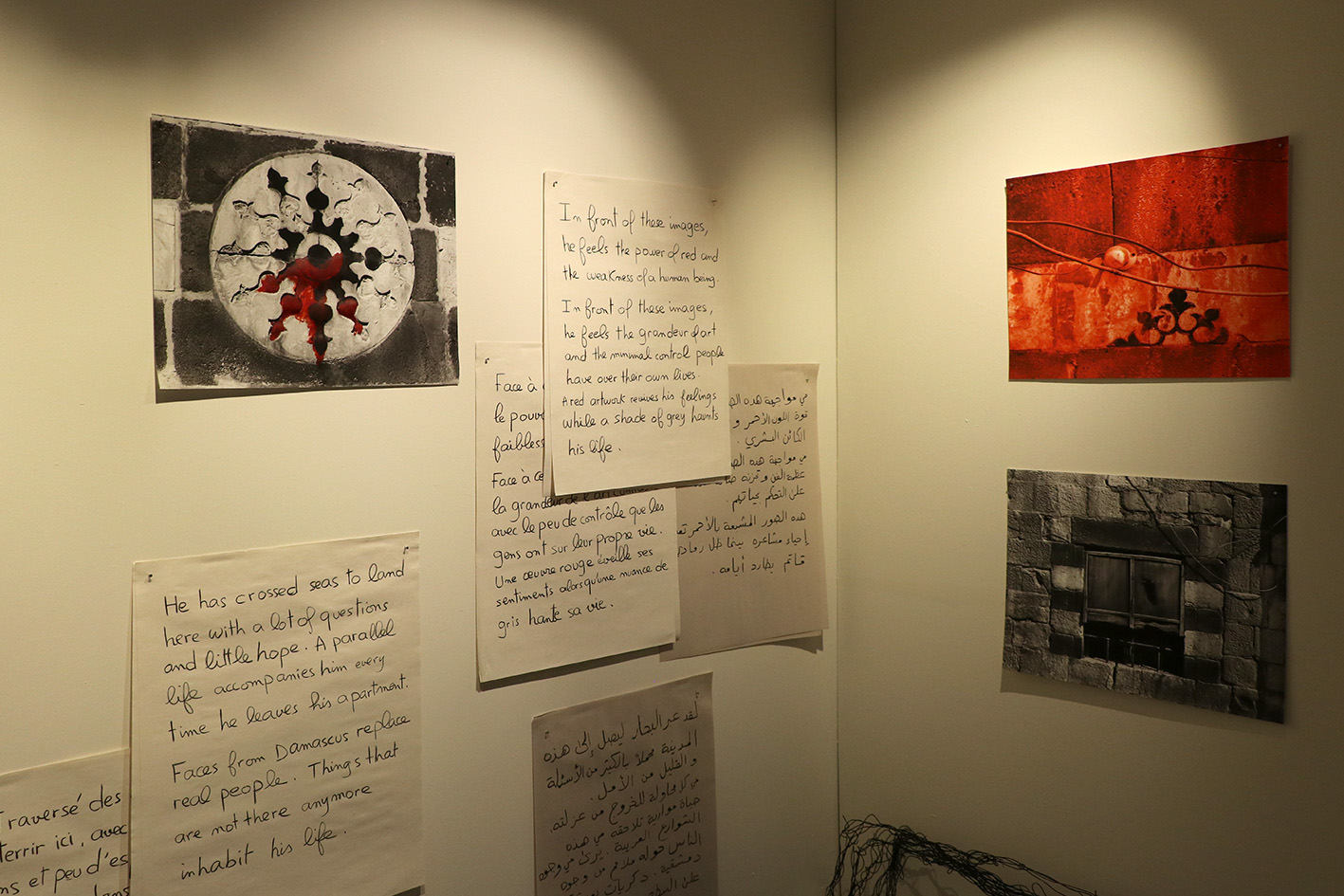

Dima: Visitors have been very moved by the intimacy of the work. They have taken the time to read and discover fragments of the different projects I shared: the struggle with the Syrian passport, being prisoner in your own self, the endless war, and home being more than a physical place . . . I left a livre d’or (a gold book) in my art studio and asked people to write the sentence that moved them the most. Everyone reacted in their own way, but a lot of people wrote the main sentence behind my The Tunnel installation, which I had handwritten in charcoal on the wall: ‘There is no black and white in the Syrian conflict, only shades of grey and too much red.’ Others wrote that, when they read my text The Prisoner (about someone who invented another self), it was the first time they’d realised how hard it was to be reminded of the conflict every day. Many Syrians who visited told me they connected deeply with a sentence from it: ‘You are tired from discussing your burning home.’

Dima Karout’s livre d’or (on the table), Syrian self-portrait and “The Tunnel” (on the wall), in her art studio at the Migration Museum. © Rudy Hajjar

My favourite corner, which I wanted people to take with them from the visit, was the Human Bridges project: ten art objects and ten texts telling fragments of friendship stories, of the human bridges that me and nine Syrian artist friends were able to build and sustain over the years. The introduction to the project reads: ‘We all met at the fine art university of Damascus, sometime around the year 2000. We came from very different backgrounds, but art brought us together. Today, we have all lost our home, we live in different cities around the world, but a fine line of friendship built through art survived and is virtually crossing continents. Our Human Bridges symbolise the power of art over conflict.’

I also designed the Arabic word jesser (it means ‘bridge’) inspired by the calligraphic style Kufi Murabba’ and asked people to be inspired by its minimalist design to create their own bridge, using the table I set up in the art studio with tools and materials, and to add their signed artwork to the installation. Visitors from all ages and backgrounds, school and university groups, all expressed a connection with this project, and told me that they had been very moved by its honesty and simplicity. The installation wall is full with people’s bridges!

A workshop in Dima Karout’s art studio at the Migration Museum. © Rudy Hajjar

Assunta: To what extent does your origin and background as a Syrian influence your art?

Dima: This is a very intriguing question that I’ve been reflecting on a lot lately, specially after the war. My art reflects who I am in many different ways. I was born and raised in Damascus, Syria. I saw the world from this perspective when I grew up. But, since 2005, I’ve been travelling: I studied my masters in contemporary art in Paris, creative writing in Montreal. I got interested in curating contemporary art, and I followed an online certificate in curatorial studies based in Berlin, with international participants. I’ve discovered ideas, cultures and met extraordinary humans on my journey. My identity has evolved and continues to evolve. My art today reflects the new person I’ve become, who absorbed all these new experiences and listened. As much as I miss my younger, lighter self, I can’t possibly say I am still the same young Syrian girl who left Syria long ago. And this is what I am trying to reflect on through We Are Made of People and Places, the new work I am researching during my residency at the Migration Museum.

Dima Karout (centre) in front of her project “We Are Made of People and Places” in her art studio at the Migration Museum. © Rudy Hajjar

On the other hand, it is impossible for me to accept this forced disconnection from my roots. I am very affected by the Syrian conflict, and my art in the last few years has been too. After receiving my Canadian passport, I wrote that ‘You can travel everywhere, but you can’t visit Damascus. You have become a prisoner of the world’. Every Syrian is trying to survive the war in their own way; I created many artworks to cope with it. The Tunnel, one of the artworks that I presented in Montreal in 2016, is on display at Room to Breathe now; it tells the thoughts of a Syrian refugee who survived an explosion and arrived in a new country in a wheelchair. One piece reads: ‘Do you want to die as a whole or to live as a half? He chose life.’ Last year, I was tired from the division between Syrians and looking to create something that might reunite us all. I created the Syrian self-portrait. It’s based on a photo of an abandoned home that I took in old Damascus in 2011 during my last visit before the war, and features a strong façade with two windows, which I transformed into grey tones and then added red ink to. It represents the human behind the wall – and us Syrians, trying to look fine, to function in the societies we live in, hiding behind a strong façade, but bleeding from the inside.

Dima Karout hanging her display of “We Are Made . . . ” in her art studio at the Migration Museum. © Rudy Hajjar

Assunta: How would you define the main advantages and challenges of being an artist–curator?

Dima: I love both. For more than 15 years I have been creating art and also curating art exhibitions and cultural events in different cities around the world. I have worked with a lot of artists and art students from different backgrounds and, whenever I am trying to present someone else’s work, I think of the artist first. I aim to preserve the uniqueness of their journey while trying, if I am working on a group show, to create a narrative between all participants. It is very challenging to find this balance, but I think that being an artist myself helps me understand the artist’s side better.

The advantages are that I understand the uniqueness of every artist, the validity of their demands, and I always try to listen. There is a sense of fragility about artists that I try to protect when I curate group exhibitions, because I went through this journey myself.

My experience with curators is different. It is sometimes very challenging when you are the only artist on the team. The curators focus on presenting the whole exhibition, sometimes working on ‘exhibiting the exhibition’, whereas the artist wants to exhibit their individual work.

I am going to be working closely with the artists invited into the art studio: Habib Sadat, The New Art Studio, Ceyda Oskay, Shorsh Saleh and Belén L Yáñez; we are going to brainstorm and try to understand each other. I aim to assemble our creativity and forces around the final group show we want to launch in June, and to curate a unique experience for all of us and for visitors.

Assunta: Sue, as curator at the Migration Museum, what was your vision for the art-studio space?

Sue: When my fellow curator, Aditi Anand, and I were discussing which rooms we would make in our exhibition exploring stories of resilience and survival in the experience of migrants, the art studio was one of the very first we came up with. We had both seen first hand in the Calais refugee camp the power of art, music and theatre to raise people up from the despair of that notorious place. We met the volunteers who were providing the means for the people there to explore their creativity, and we met those who were benefiting from it. In an earlier exhibition, Call Me By My Name, we displayed some of the art made in the camp and told the stories of those who had made it. Much later I found out from one of the artists whose work we displayed that the opportunity to show his work in the country he was trying to reach had given him hope and strength to keep going and the knowledge that he was being recognised as an artist. He is one of the artists we have invited to be resident in the art studio.

One of my main aims as a curator is to allow people the opportunity to have their voices heard and to tell their stories in the way they would want them to be heard, to give them a platform to show their work – whether this is playing music, cooking food or presenting art, photography, drama or poetry. My role as a curator is to make this happen with as little interference from myself as is possible and practical. So our vision for the art studio was to give artists a studio space to make their own, to furnish as they wished, a space to be creative: to make art, display it, sell it and to share their ideas among visitors and other artists. We were happy for it to be a messy, painty, inspiring space where our artists could feel completely at home. We felt this was especially good for migrant and refugee artists, who are still struggling to keep going in this country and for whom having an art studio, even for a short time, is a real luxury. We loved the idea of providing a space for an exhibition within an exhibition. We liked the idea of it being a changing space, inspiring for our repeat visitors and for the exciting development of the bigger exhibition. Above all, we wanted to demonstrate that the need to be creative touches us all and is a vital and enriching part of our humanity.

Assunta: How would you define your experience of working with artist–curator Dima Karout? What are your thoughts on her artwork and her art studio (Dima’s work is on display at the Museum until Monday 3 December)?

Sue: When I first met Dima, I felt strongly she would be a wonderful artist to present work in the studio. As we learnt more about each other, it became clear that Dima was the perfect person to form a collaboration with and it gradually emerged that she should take on a bigger role as artist–curator of the studio, which fitted perfectly with my idea of the curator who can step back and give others an opportunity to have a say in how the exhibition unfolds. Our discussions were sometimes heated and often confrontational but we have come to a beautiful understanding and a wonderful outcome in the way Dima has made the studio her own and interacted with her visitors. I respect and value Dima’s knowledge of what makes an artist tick and especially her sensitivity and understanding of the artist who is also an immigrant.

“The Tunnel” in Dima Karout’s art studio in the Migration Museum. © Rudy Hajjar

I have watched visitors in Dima’s studio looking at her artwork and have seen them silently witnessing her journey, her pain and her vision for a better world. I saw my daughter crying when she looked at Dima’s images of a lost Damascus. I have seen visitors making their own interpretations of the concept of Dima’s bridge between people and places and hanging them up on the participatory, inclusive space that Dima has made. I have listened to the conversations that visitors have had with her, not just about her art, but about her life, her past friends, her family, her sorrow for her war-torn country and her tentative steps towards building its future. Her studio is a powerful place to be in. Of course, it proves that making art for Dima is a lifeline. But there is more to it than that – it shows that art connects us to our own journeys through experiencing the journey of the artist. We need art to make sense of things and we need artists to express what is going on in our hearts and heads. We need to be artists ourselves.