16 September, 2015

When Alice meets Humpty Dumpty in Alice in Wonderland, illustrated here by John Tenniel, they have a famous exchange of views about the meaning of words.

‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.’

‘The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’

‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master — that’s all.”

Humpty Dumpty appears to be leading the public discourse on migration right now.

The words we choose to talk about a subject are always a significant window to our position on that subject. In the past few weeks, as they report or comment on the thousands of people attempting to find a new life in Europe, newspapers and politicians have fallen back on rather predictable language. There is, of course, the use of words associated with water – from the relatively mild ‘flow’ to ‘streams’ of migrants threatening to ‘flood’ our European countries, ‘tidal waves’ of migrants’ (Daily Mail, 26 June), ‘tsunami of Christian migration’ (Breitbart, 3 September) and ‘inundated with migrants’ (CBS, 26 August) – all of which, in their insensitive references to drowning, express concerns about the host nations rather than the people in actual danger of drowning as a result of the insecure, overcrowded and unseaworthy boats in which they make the journey across the Mediterranean.

Then there are the references to animals and insects – not just Katie Hopkins’ ‘cockroaches’ but also the Prime Minister’s ‘swarm of people’ (30 July) – terms redolent of infestation and destruction. The extent to which this is a situation out of legal control is conveyed in the use of words associated with criminality, most notably ‘marauding’, applied by Philip Hammond (9 August). And, to give a full sense of the scale of the problem, what better source to invoke than the Good Book, as Nigel Farage did with his slightly tautological ‘exodus of biblical proportions’.

The use of these words contains a fairly obvious key to the user’s position on the matter and may, as many suggest, affect (and infect) the nature of the debate. Something similar happens to the words used to describe the people making these journeys, which have long shed the neutrality they may once have had in their dictionary definitions. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED), for example, defines a migrant as ‘a person who moves temporarily or seasonally from place to place; a person who moves permanently to live in a new country, town, etc., esp. to look for work, or to take up a post, etc’; a refugee as ‘a person who has been forced to leave his or her home and seek refuge elsewhere, esp. in a foreign country, from war, religious persecution, political troubles, the effects of a natural disaster, etc.; a displaced person’; and an asylum seeker as ‘a person seeking refuge, esp. political asylum, in a nation other than his or her own’.

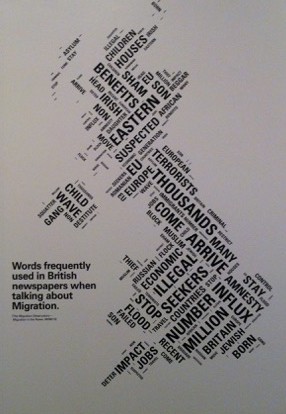

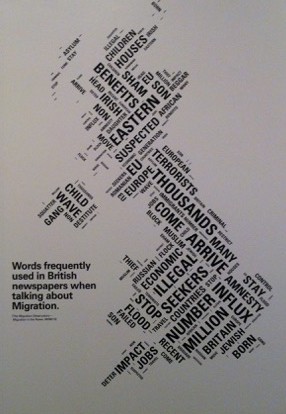

These neutral definitions are often, however, coloured by the words that are used with them – so that ‘asylum seeker’ now is most commonly associated with ‘bogus’ or ‘failed’, ‘migrant’ with ‘economic’ or ‘illegal’, etc. In Adopting Britain, the exhibition to which the Migration Museum Project contributed recently in the Southbank Centre, the Migration Observatory compiled an infographic that displayed the words most commonly used to talk about migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. It was a salutary reminder of the power of media exposure to change the way in which we use words and descriptions.

As an illustration of the way in which words absorb associations beyond their literal meaning, Professor Lentin recently questioned whether the use of the word ‘immigrant’ was appropriate when applied to Sir Edgar Speyer in a blog he wrote for us. Speyer was not, as Tony Lentin put it, one of the ‘tired, poor, huddled masses’ most commonly associated with the term although, technically, he was, of course, an immigrant.

But how do you rid words of the associations they have acquired? One response is to do as David Marsh, editor of the Guardian’s style guide, suggested in a humane and considered piece he wrote on this subject at the end of August:

Politically charged expressions such as ‘economic migrants’, ‘genuine refugees’ or ‘illegal asylum seekers’ should have no part in our coverage. This is a story about humanity. Reporting it should be humane as well as accurate. Sadly, most of what we hear and read about ‘migrants’ is neither.

Any modern-day Humpty Dumpty, of course, is free to disagree with this. But then we all know what happened to Humpty Dumpty, don’t we?

2 September, 2015

For every exhibition that is put on, there is always another: the exhibition that could have been put on had there been world enough and time. When you’re trying to condense more than six hundred years of German–British history into 17 panels of information, there are bound to be omissions that haunt you. For Cathy Ross, the curator of our Germans in Britain exhibition, one such omission was the story of Sir Edgar Speyer. Speyer, born in the United States to German Jewish parents, was a British-naturalised merchant banker and philanthropist, who was unceremoniously drummed out of Britain in May 1915, almost exactly one hundred years ago. The only part of his story that is on show in the Germans in Britain exhibition is the quotation that tops the banner on the First World War – a quotation from Lord Charles Beresford, delivered at a women’s anti-German rally in the Mansion House: ‘The most dangerous enemies in our midst are the rich, independent, naturalised Germans in high social positions … still Germans at heart. [They are] not wanted here.’

It has long been accepted that Sir Edgar Speyer was the most obvious target for Beresford’s words. The guest blog that follows has been written by Tony Lentin, the author of a new book on Speyer. We should bear in mind that Sir Edgar Speyer was by no means the only German-born Briton to be treated in this way, though his profile was higher than most.

King of the Underground turned pariah

Without Sir Edgar Speyer, there would be no London Underground and no Proms, and there would have been no Captain Scott’s expeditions to the Antarctic.

Born in the United States to Jewish immigrant parents from Germany, Sir Edgar Speyer (1862–1932) was a celebrated figure in the financial, cultural and political life of England before 1914. A merchant banker, he headed the company which financed the construction of the deep-level ‘tubes’. He became known as ‘King of the Underground’, subsequently taking over London’s entire transport system.

![King of the Underground[1]](http://migrationmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/King-of-the-Underground1-e1441117688364.jpg) It was his personal generosity in the 12 years before the war that alone saved the Proms from bankruptcy and extinction and guaranteed their accessibility to a popular audience. He was a patron of many early 20th-century composers, including Elgar, Richard Strauss, Debussy and Percy Grainger. A munificent donor to the King Edward VII hospital and many other medical and charitable causes, he co-founded the Whitechapel Art Gallery, and he raised funds for Scott’s expeditions to the Antarctic. He was a supporter of the Liberal Party, the friend of Winston Churchill and the then prime minister, Herbert Henry Asquith, and a regular guest at Downing Street – he was made a baronet in 1906 and a member of the Privy Council three years later.

It was his personal generosity in the 12 years before the war that alone saved the Proms from bankruptcy and extinction and guaranteed their accessibility to a popular audience. He was a patron of many early 20th-century composers, including Elgar, Richard Strauss, Debussy and Percy Grainger. A munificent donor to the King Edward VII hospital and many other medical and charitable causes, he co-founded the Whitechapel Art Gallery, and he raised funds for Scott’s expeditions to the Antarctic. He was a supporter of the Liberal Party, the friend of Winston Churchill and the then prime minister, Herbert Henry Asquith, and a regular guest at Downing Street – he was made a baronet in 1906 and a member of the Privy Council three years later.

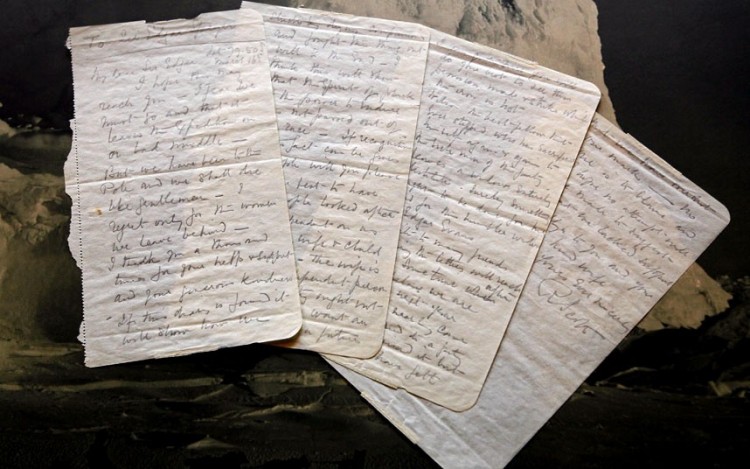

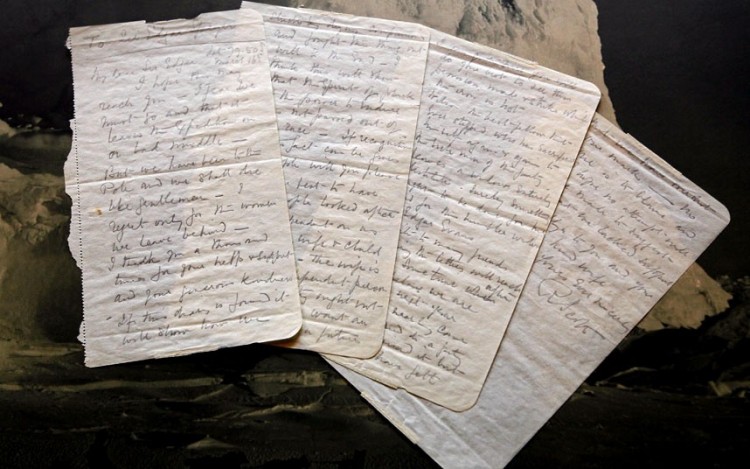

Among the last letters written by Captain Scott was this letter to Sir Edgar Speyer, the honorary treasurer of the fundraising committee behind Scott’s trip. The letter, sold at auction in 2012 for £163,000, ends: ‘Goodbye to you and your dear kind wife’.

On the outbreak of war, however, as a result of his German parentage and connections this remarkable man became a pariah. He was hounded out of Britain in May 1915 by unscrupulous politicians and an irresponsible press. In 1921 (by which time Speyer was in the United States) he returned to face a judicial tribunal, under the newly enacted Aliens Act, and was found guilty of disloyalty and disaffection and of communicating and trading with Germany in wartime. In his foreword to my book, Banker, Traitor, Scapegoat, Spy? The Troublesome Case of Sir Edgar Speyer, the distinguished jurist Sir Louis Blom-Cooper, QC, comments that the procedure ‘reflected no credit on a legal system that had always prided itself on protecting the individual against the might of the state’.

Following the tribunal’s finding, however, Speyer was stripped of his British citizenship and membership of the Privy Council.

When he died in 1932, the Morning Post described his downfall as ‘a minor tragedy of the war’. My book is the first detailed account of this unsavoury episode in British–German relations. It re-examines Speyer’s case from documents newly released, presents the evidence and invites the reader to decide whether he was an innocent victim, a scapegoat, or a traitor to his adopted country.

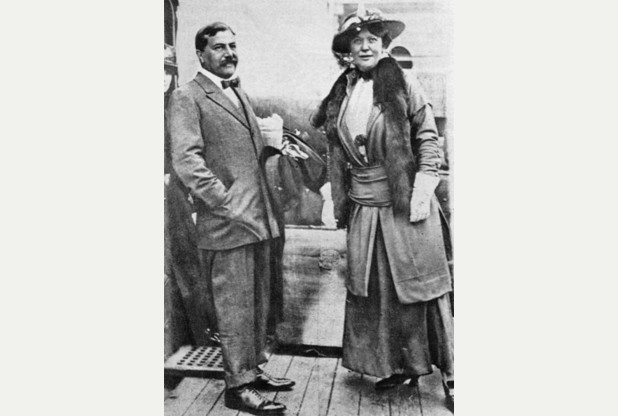

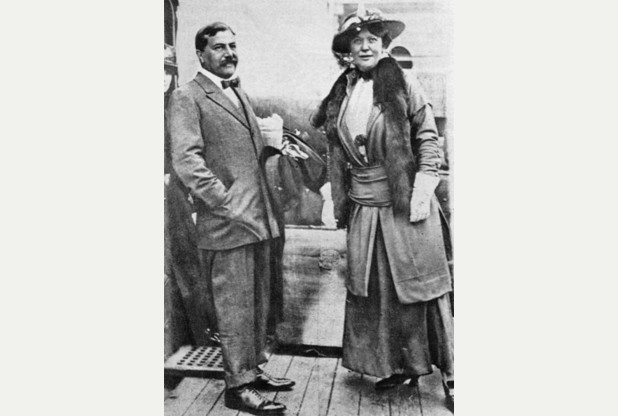

Sir Edgar and Lady Leonora Speyer, photographed in the early 1920s, around the time of his appearance before the tribunal under the Aliens Act

I have campaigned for Speyer’s generous acts of philanthropy to be recognised today. I am not alone in seeking recognition for his critical support for so many British causes. In October 2014, a plaque was unveiled in Speyer’s honour at the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge. Earlier this year, BBC 3 radio presenter Dr Kate Kennedy told listeners that she felt Speyer should be honoured with a statue for saving the Proms from collapse.

In November 2014, almost a hundred years after Lord Beresford’s inflammatory statement, Lord Black of Brentwood said in the House of Lords: ‘A century on, when we can look back with calm perspective on some of the events that happened in the heat of the moment, it would be right to ensure that the record is set straight and that the contribution to music, science and the arts of this man, who was so unfairly treated, is properly recognised with a fitting memorial.’

Postscript: On Saturday 12 September this year, the Last Night of the BBC Proms, the BBC will reflect Edgar Speyer’s contribution to the Proms in the presentation on BBC Radio and Television and in the printed programme. The BBC, which took over the financing and running of the Proms in 1927, has said that Edgar Speyer exemplified ‘a spirit of patronage and public service’ that it is proud to be continuing.

Tony Lentin has posted this further postscript on 15 September:

An e-mail to me from the BBC on 14 August said: ‘We will use this opportunity to reflect Edgar Speyer’s contribution to the Proms in the presentation on BBC Radio and Television and in the printed programme. Speyer’s is a very interesting story in the history of the Proms and we are pleased to be able mark his connection through this particular piece of repertoire.’

I have not seen the printed programme, but the BBC2 presentation consisted of the bare mention of ‘the philanthropist Sir Edgar Speyer’ in connection with Till Eulenspiegel. That was all. Rapid coverage of Proms history featured Newman, Henry Wood and the BBC. Nothing on ‘The Man Who Saved the Proms’.

My verdict, on pages 175–6 of my book, stands:

When the Promenaders join in ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ or Parry’s ‘Jerusalem’ on the last night of the Proms, they pay homage to the garlanded bust of Sir Henry Wood, but not to his indispensable patron. They will not know that Parry wrote to express to Edgar his shame at the outcry against him, that Elgar wrote to him of ‘the indebtedness of the English people to you “a great uplifting force” in the nation’s musical life.’

There will be a proper commemoration of Speyer’s contribution at two concerts this autumn: Hay Music on 10 October, and Chelsea Concerts on 9 November.

Professor Antony Lentin is a senior member of Wolfson College, Cambridge, a barrister and formerly a Professor of History and law tutor at the Open University.

Lentin, Antony (2013) Banker, Traitor, Scapegoat, Spy? The Troublesome Case of Sir Edgar Speyer. London: Haus Publishing.

Tony Lentin http://www.edgarspeyer.co.uk/index.php

![King of the Underground[1]](http://migrationmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/King-of-the-Underground1-e1441117688364.jpg) It was his personal generosity in the 12 years before the war that alone saved the Proms from bankruptcy and extinction and guaranteed their accessibility to a popular audience. He was a patron of many early 20th-century composers, including Elgar, Richard Strauss, Debussy and Percy Grainger. A munificent donor to the King Edward VII hospital and many other medical and charitable causes, he co-founded the Whitechapel Art Gallery, and he raised funds for Scott’s expeditions to the Antarctic. He was a supporter of the Liberal Party, the friend of Winston Churchill and the then prime minister, Herbert Henry Asquith, and a regular guest at Downing Street – he was made a baronet in 1906 and a member of the Privy Council three years later.

It was his personal generosity in the 12 years before the war that alone saved the Proms from bankruptcy and extinction and guaranteed their accessibility to a popular audience. He was a patron of many early 20th-century composers, including Elgar, Richard Strauss, Debussy and Percy Grainger. A munificent donor to the King Edward VII hospital and many other medical and charitable causes, he co-founded the Whitechapel Art Gallery, and he raised funds for Scott’s expeditions to the Antarctic. He was a supporter of the Liberal Party, the friend of Winston Churchill and the then prime minister, Herbert Henry Asquith, and a regular guest at Downing Street – he was made a baronet in 1906 and a member of the Privy Council three years later.