Navrati Puja, 2013

In the third of our features on photographers who have contributed to our 100 Images of Migration exhibition, we feature the work of Guy Corbishley, who submitted the photos of ‘Speaker’s Corner’ and ‘EDL protest’, two images that form part of what Guy calls his ‘continuing work exploring protest, politics, diverse cultures, human rights and the modern-day migration experience in Britain’. Both photographs are regular favourites with visitors to the exhibition, many of whom appreciate the ability of ‘EDL Protest’ in particular to draw three elements of this experience – the police presence, the EDL protesters and the young British Asian woman – in a composition that hovers uncertainly between dark and light. The same charge pulses through the photos Guy has selected for this blog, all of them stunning compositions which are never quite as straightforward as they first look. Needless to say, we are thrilled to be able to feature Guy’s photographs and deeply grateful to him for his involvement in our project.

Guy has provided a brief note on himself and captions to the photographs that follow.

I’m a full-time freelance photojournalist and documentary photographer. Currently I divide my time between working in London and abroad, supplying editorial, commercial and cultural imagery to a wide range of clients and publications in this country and across the world. One of my long-term personal projects involves documenting the last remaining Orthodox Pilgrims of Grabarka in east Poland and covering the geo-political conflicts of Ukraine/Euromaidan.

You can e-mail me for more details: my address is at the end of this blog.

Every year thousands of Orthodox Christian pilgrims arrive at the holy mount of Grabarka in east Poland, some journeying many hundreds of kilometres by foot. The pilgrims gather at Grabarka Hill to celebrate the Feast of the Transfiguration in August. The hill and church are the holiest location for Poland’s few remaining Orthodox Christians.

The Euromaidan is the name given to a wave of demonstrations and protests in Ukraine. These began on the night of 21 November 2013, when a large number of public protests demanded closer integration with Europe. The protests evolved into deadly riots that claimed more than 100 lives and led to the removal of President Yanukovych and his government.

British-based Ukrainians march and rally for peace in central London on National Vyshyvanka Day. Dressed in Vyshyvanka – the traditional Ukrainian ethnic embroidered dress, which includes floral head wreaths – the marchers demonstrate adherence to the idea of national identity, unity and patriotism.

British-based Eastern Orthodox Christians, predominantly of Russian origin, gather outside the Russian church (Diocese of Sourozh) in Knightsbridge, London, where Bishop Elisey gives his Easter blessings to their Pascha (Easter) baskets containing decorated eggs and cakes.

Campaigners, families of detainees and former detainees demonstrate outside Harmondsworth Immigration Removal Centre, Middlesex. Their protest is against the process increasingly used to fast-track the deportation of asylum seekers from the UK. The civil rights activist group Movement for Justice and its supporters are campaigning for the closure of the detention centre and the launch of a full public inquiry into the alleged physical, sexual and mental abuse of detainees, which many of their complaint reports have documented.

Two Muslim women take a break and prepare for noon prayers during protests outside the Egyptian Embassy in London. The protests were part of the demonstrations across the world, known as the Arab Spring uprising.

6-year-old Inka reads names from the Polish war memorial in South Ruislip, London. Every year British-based Poles march and hold service at the war memorial in commemoration of the ‘Cursed Soldiers’. The Cursed Soldiers (or Doomed Soldiers) were a partisan group battling for independence in the later stages of the Second World War and afterwards against the communists. Inka was named after Danuta ‘Inka’ Siedzikowna, 1928–47, a medical orderly in the 4th Squadron of the Polish Home Army.

Local Muslim girls help out during the 35th London Marathon as it passes down Deptford’s Evelyn Street, south-east London.

Antonia Bright, from the civil rights activist group Movement for Justice, leads a protest outside Holloway prison in north London. Protesters were calling for the release of a female inmate who had been imprisoned after being beaten by a prison guard (since suspended) while she was protesting at Yarl’s Wood Immigration Removal Centre against the deportation of a fellow detainee.

Veteran Gurkha Corporal Dilbahadur Thapa, 83, who served in the 10th Gurkha Rifles Regiment from 1948 to 1961, is reunited with a replica of his original war medal on the seventh day of a hunger strike opposite Downing Street in London. The hunger strike was carried out by two groups of Gurkhas – Gurkha Satyagraha and the BWHR British Gurkha Project –before being temporarily suspended by Lord Ahmed, who agreed to intervene and take up matters with Whitehall and Philip Hammond MP, Secretary of State for Defence. BWHR British Gurkha Project is calling for Gurkhas to be awarded British citizenship rather than settlement rights, which would entitle them to service pensions and to have their children come to live with them from Nepal. Currently pension rights for ex-Gurkha soldiers differ from those of the British soldiers with whom they served. Some Gurkha veterans receive no pension.

A local Sikh man crosses the road to place flowers on Wellington Street in south-east London the day after Royal Fusilier solider Lee Rigby was murdered by Islamic extremists.

British-based Ukrainians staged continuous solidarity protests throughout London as part of the 2014 Euromaidan demonstrations. Opposite the Russian Embassy there was a small measure of rejoicing at the news that the jailed opposition leader, Yulia Tymoshenko, had recently been released from custody in Kharkiv. The Euromaidan is the name given to a wave of demonstrations and protests in Ukraine which began on the night of 21 November 2013, when a large number of public protests demanded closer integration with Europe. The protests evolved into deadly riots that claimed more than 100 lives and led to the removal of President Yanukovych and his government.

Performers of Molodyi Teatr (Young Theatre) perform the play ‘Bloody East Europeans’ at the Ukrainian Institute in London, satirising the eastern European migrant experience in the UK. The play was written by Uilleam Blacker and directed by Olesya Khromeychuk.

On 24 February 2014 a few hundred British-based Poles rallied opposite Downing Street in London to protest against the on-going discrimination of Polish people living in the UK. The protest highlighted the recent attack on a Polish biker in London who had been assaulted for displaying the Polish flag on his helmet. The protesters also raised other issues raised such as populist politicians, David Cameron among them, who used Polish and other eastern European migrants as scapegoats for a faltering economy.

Guy Corbishley

guycorb@gmail.com

On Monday 12 and Tuesday 13 October, at the University of Sheffield’s ‘Migrants in the City’ conference at Cutler’s Hall, there’s a sneak preview of a project by Jeremy Abrahams that is going to be shown in full in 2016. In this guest blog, Jeremy explains the background to his project and what he was hoping it would show.

In Bloody Foreigners, Robert Winder tells a lovely tale of the origin of the name of John O’Groats, the northernmost tip of mainland Britain. The name of the village is not, as you might think, Scottish, nor Irish, but is actually derived from Jan de Groot, a Dutchman who arrived in south-east England but moved north to start a ferry service between Scotland and Orkney. Winder’s point, of course, is that immigration has always been a part of our history, and always will be. What seems to change is attitudes towards it.

At the end of 2013 I was new to professional photography and looking for a personal project. As someone born here but whose family came from Lithuania in the nineteenth century, immigration was uppermost in my thoughts. Partly inspired by a friend who came to Sheffield from Prague on the Kindertransport in 1939, leaving her family behind, I decided to photograph one person who migrated from overseas to Sheffield in every year from 1939 to 2016. This was to be my ‘Arrivals’ project.

Each subject chooses where in Sheffield they would like their picture to be taken. So ‘Arrivals’ is a portrait of the city, of the pattern of migration and of 77 individuals, documenting and celebrating the diversity of Sheffield’s population.

Of course, an image can say something about the subject’s life, but it cannot fully explain why they left their country of origin and came to Sheffield. So each subject’s image is accompanied by a short piece of text – in their own voice – which enhances the visual story and makes us aware of the uniqueness of each person’s experience.

Like most major urban areas of the UK, Sheffield has substantial communities of Afro-Caribbean and Asian origin.

George Grant arrived from Jamaica in 1965. ‘’I’m the youngest of 10 children. My dad – a joiner – came to Sheffield with my oldest sister in 1960 and I came with my mum and five other siblings five years later. When I was a little older, Sheffield United wanted to sign me as a schoolboy, but I didn’t fancy all the training; I just like playing.”

Mohammed Younis arrived from Pakistan in 1958. “My grandfather came before the Second World War, my father came in 1952 and I arrived from Pakistan as an 11 year old in 1958. In 1967 I joined the council’s Youth Service and in time completed my education, attending the universities of Durham, Manchester and Bradford, achieving an MA in International Politics and Security Studies at the latter.”

Sheffield, as the first ‘City of Sanctuary’, has a track record of welcoming refugees whose stories reflect the troubles in their countries of origin. Many refugees from the Pinochet dictatorship settled in Sheffield during the 1970s.

Isilda Lang arrived from Chile in 1977. “As a refugee escaping political persecution it was terrible to suffer torture, fear and nightmares of persecution. Being displaced from the place you were born is not easy, because you have to readjust to everything, practically to be reborn. The language was the hardest thing to learn – it took me five years to have the confidence to speak English. I was part of the Red Cross when another tragedy happened in my life: the Hillsborough disaster of April 1989, where I worked alongside doctors and nurses on the day.”

More recent events around the world have also brought people to Sheffield.

Habib Josefi arrived from Afghanistan in 2005. “The day I was told that I could live in England was the happiest of my life – I would no longer be forced to move from country to country in search of sanctuary. My family had been forced to flee from Afghanistan to Iran three times as regimes changed and foreigners intervened in the country. When the Taliban took over, I was forced to flee yet again. I moved around the world trying to find a permanent home, spending time in Iran, Turkey and Russia before finding temporary sanctuary in Cuba. I learned Spanish well enough to register for a university course and was halfway through my first year when I was told I must find somewhere else to go. That somewhere was the UK, which accepted me as a refugee.”

Of course the free movement of labour within the EU has also brought new Arrivals.

Magdalena Garpiel arrived from Poland in 2006. “My husband Adam and I were running a successful business with a partner in Bielsko-Biala when we decided to leave Poland. We wanted to learn another language and meet new people – a new adventure.”

And finally, the story of a young woman who came to Sheffield as a student, to find herself separated from her family during the bombing of Gaza by Israel in 2014.

Malaka Mohammed Shwaik Arrived from Gaza in 2013 “In 2013 I was given a fee waiver to study for a Masters in Global Politics and Law at Sheffield University. Travelling here from Gaza/Palestine was not easy. I experienced humiliation and discrimination many times when I tried to cross the border from Gaza. It took me some time to start engaging with the community around me, but since those early days I have spoken in many conferences throughout Europe to raise awareness of the situation in Palestine.”

Jeremy Abrahams

‘Arrivals’ project: www.jeremyabrahams.co.uk/arrivals

Subjects are still needed! Please contact me on info@jeremyabrahams.co.uk

A small number of ‘Arrivals’ images can be seen at the University of Sheffield’s ‘Migrants in the City’ conference at Cutler’s Hall on Monday 12 and Tuesday 13 October 2015.

The full ‘Arrivals’ exhibition will open at Weston Park Museum in Sheffield in late summer 2016.

War has always been one of the major causes of migration, with refugees fleeing countries torn apart by conflict. Most of these refugees hope to return to their country once peace is restored, although obviously (as, for example, our blog on the Polish Government in exile showed) this may turn out to be impossible. In this guest blog, Jill Rutter, a trustee of the Migration Museum Project, writes about one of the less well-known migration stories of the First World War.

Most of the events to mark the centenary of the First World War have focused on fallen combatants and battle sites. There has been little commentary about the civilian casualties of the Great War, among them many millions of refugees. But there is much we can learn from the settlement of more than 250,000 Belgian refugees in the UK. Their arrival was the largest refugee movement in British history and, perhaps surprisingly, this country was truly a sanctuary.

The Belgians started to flee in August 1914, after the German invasion, with most of this group of refugees arriving in the first months of the war. Later in the conflict another 175,000 Belgian soldiers took refuge in the UK, many of them convalescing from war injuries.

Refugees fleeing Antwerp, 1914. © Imperial War Museum

The newly arrived Belgians were billeted all over the UK, not only to urban areas, but also to small rural market towns. Agatha Christie is said to have based her character, Hercule Poirot, on a Belgian refugee she met in Torquay. The fullest account of the settlement of Belgian refugees is given in Belgian Refugee Relief in England During the Great War by Peter Calahan. In the last year a number of local museums have mounted exhibitions which include Belgian stories; Otley Museum’s Great War commemorations included a collection of Belgian refugee stories.

It was initially a charity – the War Refugees Committee – that assisted these refugees. But by autumn 1914, the charity was overwhelmed and the government took responsibility, with the Local Government Board acting as the lead department. The programme was led by senior civil servants and, at ministerial level, by Walter Long, whose political epitaph largely comprised the successful integration of the Belgians. This was a milestone: the first time that Government had taken policy responsibility for the settlement of refugees.

Yvonne van den Broeck, a Belgian child who came to the town with her parents, sister and two brothers. Image thanks to Otley Museum and Archive Trust.

The Local Government Board organised the dispersal of the Belgians to reception camps, where they stayed until more permanent housing was found. Most Belgian children were sent straight to local schools, where they were welcomed as a visible means of supporting the war effort. School inspections of the period noted:

Our inspectors say that all over the country these children are finding their way into the elementary schools in a very normal and easy manner … The Belgian children seem very happy at school, through sometimes they do not like leaving their compatriots.

(Cited in a report of Local Government Board, 1916).

Tensions between Belgian refugees and the host community were rare. The media portrayal of the refugees helped ensure a warm welcome: the Belgians were fleeing the advancing German army and were portrayed as plucky and brave heroes in the popular press. This absence of hostility was even more remarkable because this period of history was marked by growing anti-alienism.

The Local Government Board encouraged host communities to set up Belgian Refugee Committees to assist in the resettlement of the refugees. There were 2,500 committees of volunteers by 1916 and there has not been such broad public engagement with the reception migrant reception since then. These committees organised relief for the refugees, providing food, clothing and other assistance.

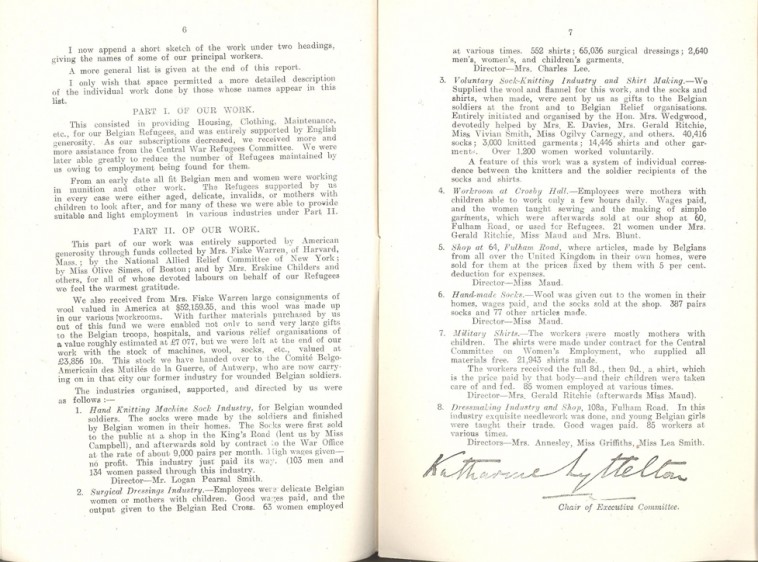

Pages from a booklet listing work done by the Chelsea War Refugees’ Fund, including the provision of housing, clothing and maintenance for the Belgian refugees. © QMUL Library

By 1916 the Belgians had started to return home – the 1921 Census recorded fewer than 10,000 Belgian nationals settled in the UK. Save a memorial in the Victoria Embankment, there is now little evidence of this remarkable migratory movement. But at a time when there are concerns about the integration of new migrants and the segregation of our towns and cities, there are lessons to be learned from the reception of the Belgian refugees. In particular, the Government requested that host communities should see it as their responsibility to welcome new arrivals. Perhaps this is a value that we should resurrect today and think about ways we can welcome new migrants.

The Belgian Refugee Memorial in London, located on the Embankment opposite Cleopatra’s Needle.

Jill Rutter is a trustee of the Migration Museum Project. Moving Up and Getting On, her new book on migrant integration, was published by Policy Press in July 2015.