24 May, 2017

Standing at a crossroads

What have been the pivotal moments, the forks in the road, the lines in the sand in the history of migration in this country? And was the referendum on 23 June 2016 one of those moments?

The pivotal moments in a person’s, or a country’s, life are always compelling hooks to hang narratives on, and fertile ground for speculation. What if Hitler hadn’t turned his attention away from Britain and towards the Soviet Union in 1941? What if the Spanish Armada had had better weather and organisation? What if King Harold hadn’t had to face the Norwegians at Stamford Bridge a mere three weeks before facing the Normans at Hastings? What if England hadn’t beaten Germany in the 1966 World Cup final? The bookshelves in the historical section of bookshops and libraries are full of books that either speculate about what might have happened if the outcome of these events had been different or use the outcomes themselves as a means of defining the particular character of our country.

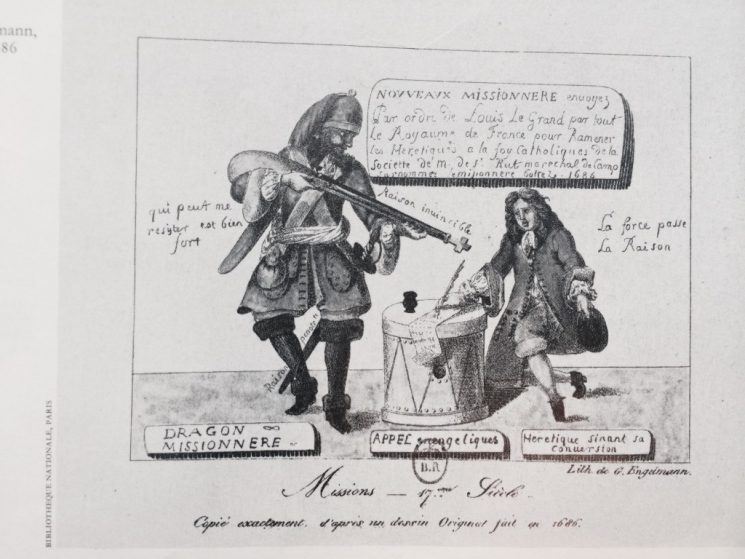

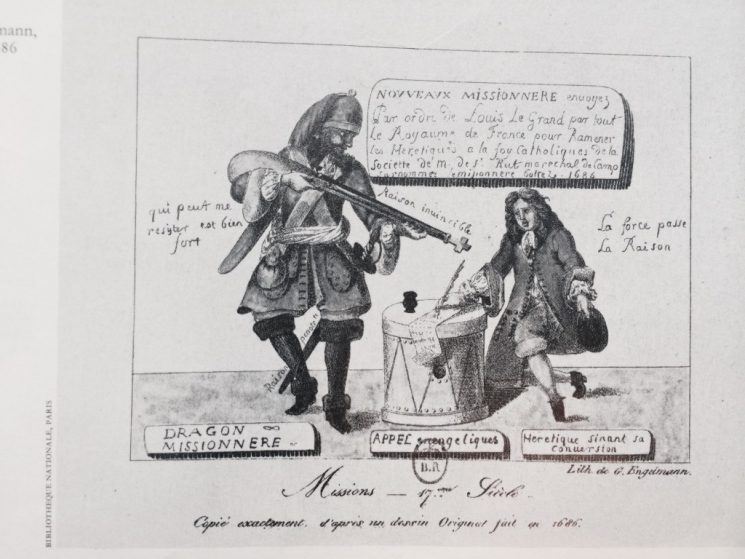

An image illustrating a French dragoon forcing a Huguenot to convert to Catholicism, following Louis XIV of France’s revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 and his sanctioning of these intimidating ‘dragonnades’.

Literature and personal stories are full of such moments, too, ‘The Road Not Taken’ by Robert Frost being one of the best known:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

In terms of this country’s relationship with Europe, two roads certainly diverged last June, and continue to do so, and the road we have taken as a country has made all the difference as far as campaigners on either side of the referendum are concerned. But what will the long-term difference be in terms of our attitudes to people born outside the UK? And are there comparable moments in our history where, faced with a stark choice, we took one road rather than another? And (last question for a while), if so, what were the outcomes of those decisions?

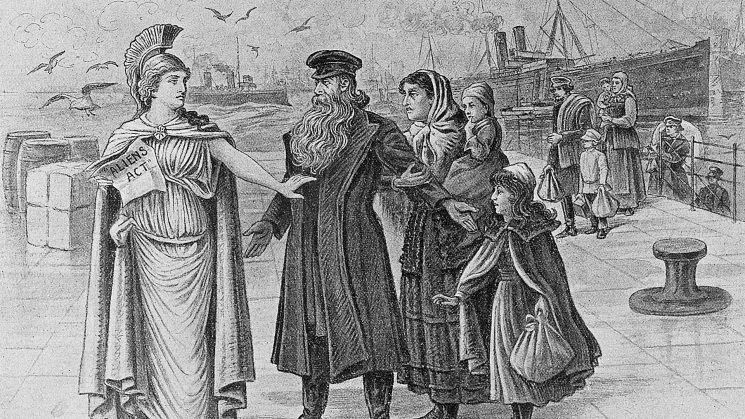

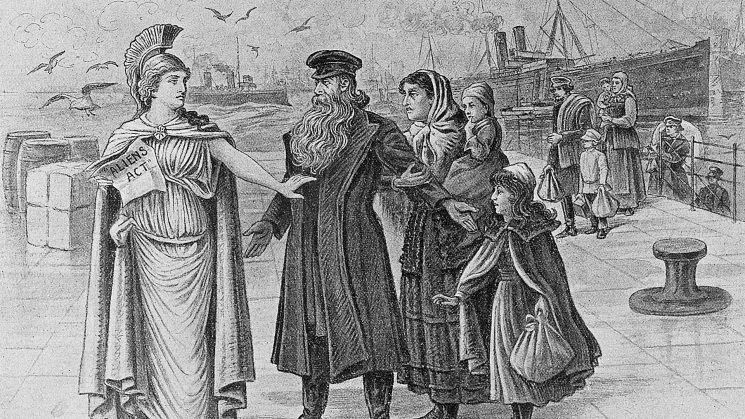

The original caption to this cartoon, printed in the wake of the 1905 Aliens Act, has Britannia saying “I can no longer offer shelter to fugitives. England is not a free country.” ©The Jewish Museum

These are some of the questions we plan to explore in a new exhibition called No Turning Back: Seven Migration Moments That Changed Britain, which we hope to open in the autumn of this year in our new space at The Workshop in Lambeth, London. The earliest of these seven moments is 1290, when, under the reign of Edward I, all Jews were banished from England; the most recent (if you can apply that adjective to a future date) is 2020, the date at which it is estimated that mixed-race Britons become the largest minority ethnic grouping. Moments in-between include the Huguenots, the East India Company’s arrival in India, the 1905 Aliens Act, the first scheduled long-haul jet service and Rock against Racism.

We’ve selected these seven moments because they seem to us to define key moments in our history but also because they echo so much of what is happening today. The expulsion of the Jews in 1290 was the only point in our history (so far) when we expelled a whole race or creed – but it has obvious parallels with what is happening today, both in the wake of post-referendum calls to East European residents and others to ‘go back to your own country’ and in the more negative connotations of ‘reclaiming our borders’. The arrival of the Huguenots in 1685 and after is cited as one of the great success stories of immigration – but how different was the reaction then to that mass arrival of foreign labour from the reaction now to today’s migrants, economic or other? And what are the factors that lead to one immigrant being accepted or successful while another is deported or deemed to have ‘failed’ to integrate?[/caption]

The title of our exhibition has since been appropriated by our prime minister and the advocates of a hard Brexit – but actually, when you take the long view of history, for all the defining moments from which there seemed to be no turning back there were a significant number of others when things just happened or changed because of a technological development (such as the availability of affordable, long-haul air transport), or an environmental disaster or because of the human capacity to form attachments. History is nothing if not unpredictable.

One of several blue plaques around the country that mark places associated with Jewish communities before their expulsion in 1290. © noli’s on Flickr

We’re conscious that others will argue that there are seven better moments we could have chosen for our exhibition – and we’d like that discussion to be part of the exhibition. There will be facts and figures, of course, but there will be many more personal stories, ideas and reflections – and we’d like that to be part of the visitor engagement in the exhibition, too. As with everything we’ve done so far, we are planning to enrol the visitor as much as possible in the content of what is on show.

For each of these moments we are already working with a team of academic and artistic advisers, teasing out the human stories of the event and attempting to reveal the consequences of that moment. As with our most recent exhibition, Call Me By My Name: Stories From Calais and Beyond, this will be a multimedia display with much new material, and with each section involving an interactive element for visitors to engage with.

We would love to hear from you if you:

- • would like to volunteer for the exhibition (or for the project)

- • would just like some more information

If you would like to get in touch, please contact Aditi Anand (aditi@migrationmuseum.org), Sue McAlpine (sue@migrationmuseum.org), Andrew Steeds (andrew@migrationmuseum.org) or Faiza Mahmood (faiza@migrationmuseum.org).

28 April, 2017

One of the clear highlights of our ‘Imprints’ walk last October (to judge from the feedback of walkers) was Bill Bingham’s rendition of the ‘Strangers’ speech from Sir Thomas More. Bill, a tireless friend of the Migration Museum Project and the mastermind behind the video tent in our current exhibition of Call Me By My Name in the Migration Museum at The Workshop, will be performing the same speech this coming Monday. His account below gives the background to the speech and the details of Monday’s activities.

The Stranger’s Case

There is a very special – and topical – 500th anniversary coming up this Bank Holiday Monday (1 May).

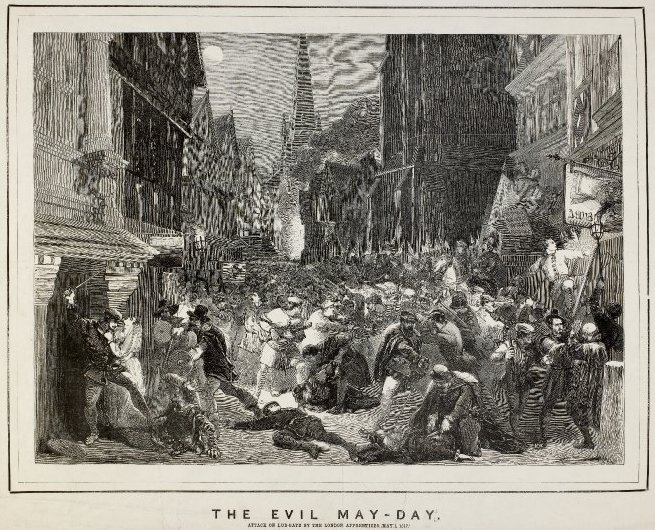

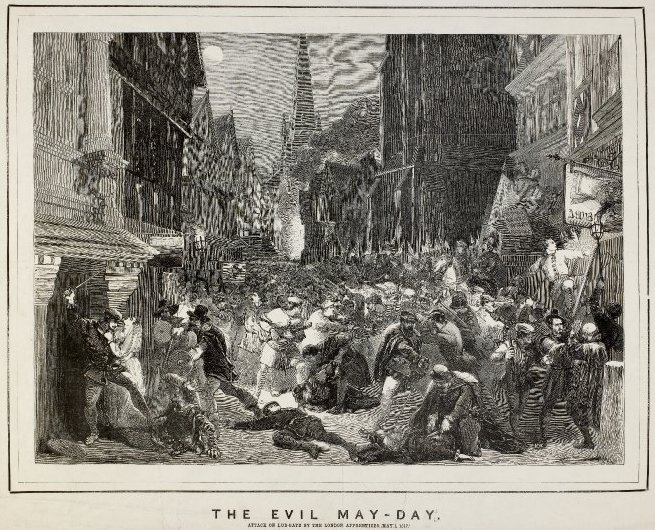

Evil May Day riot in Cheapside, 1517.

St Martin’s le Grand near St Paul’s Cathedral was the scene of a huge anti-immigration riot in 1517 aimed at the Dutch, Flemish and other foreigners, or ‘strangers’ as they were called. The then Under-Sheriff of London, Thomas More, was called on to try and quell the mob. The event is referred to in history as ‘Ill May Day’, or ‘Evil May Day’.

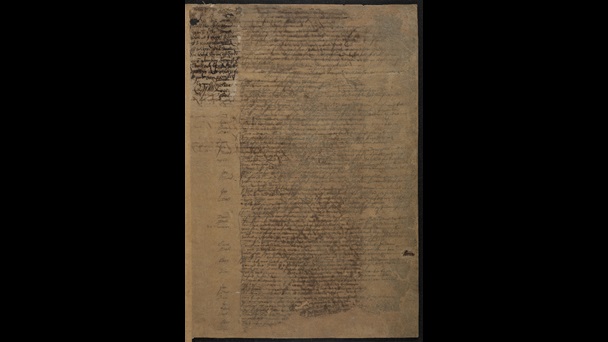

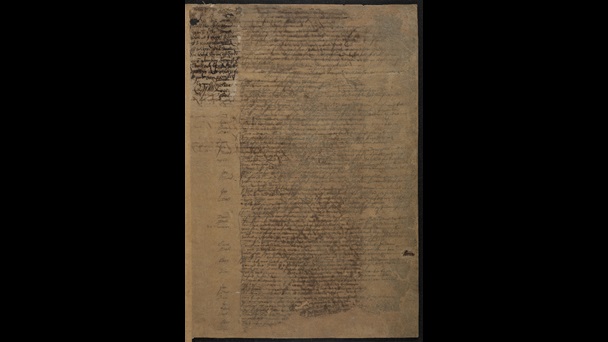

A speech by William Shakespeare from the late-16th/early-17th Century play Sir Thomas More, written in Shakespeare’s own hand, is held at the British Library, along with other sections of the play.

A page from the surviving playscript of ‘Sir Thomas More’, showing Shakespeare’s ‘Strangers’ speech. The script is held at the British Library. © The British Library.

Three actors, Tim Bentinck (who plays David Archer in the BBC’s The Archers), Bill Bingham and Lachlan McCall are marking the anniversary with a 10–15 minute extract from Sir Thomas More, including the Shakespeare/More call for the rioters to disperse,in four venues around London:

- 10.30 – the new headquarters of the Migration Museum at The Workshop in Lambeth

- 13.00 – Postman’s Park close to St Martin’s le Grand

- 17.00 – Bankside, the steps outside Shakespeare’s Globe

- 19.45 – Montague Close, behind Southwark Cathedral

If there are any more details, they will be added to this blog over the weekend.

Young apprentices attacking ‘strangers’ in the days leading up to the Evil May Day riots of 1517. © British Museum.

31 March, 2017

After Khalid Masood’s attack on Westminster last week, both Birmingham and Islam were singled out for critical comment in some of the nation’s press – Birmingham being once again branded the UK’s prime jihadist recruitment centre, and Islam criticised for its callousness, as evidenced by the photograph of a young Muslim woman walking past one of the victims with apparent disregard. Jamie Lorriman, who took the photo, felt he had to defend the young woman against those who had used his photo to further an anti-Islam agenda, clarifying the context and drawing attention to her obvious distress. And Tariq Jahan, hero of the hour in the 2011 riots in Birmingham, gave an equally stout defence of his home city, drawing particular attention to its cultural cohesion, the very quality some of the press had claimed it lacked.

Against this background, Liz Hingley’s blog feels particularly timely. Born in Birmingham, she documents her birth city’s multi-faith communities with understanding and affection, projecting the power of religion to build bridges rather than to burn them. For more information of Liz’s work, see the links at the end of her piece.

The flyover leading from Birmingham city centre to the two-mile stretch of Soho Road. The area has one of the highest immigration and also poverty rates in the city. © Liz Hingley

Under Gods

Growing up in Birmingham, one of the UK’s most culturally diverse cities and home to citizens of more than 90 different nationalities, I was the only white British girl in my nursery class. I ate sweet Indian treats at friends’ birthday parties and attended Sikh festivals in the local park. After travelling abroad and living in other cities, I became aware of the particularity of my upbringing. I developed an interest in the growth of multi-faith communities in European inner cities, and the attendant issues of immigration, secularism and religious revival.

Between 2007 and 2009, I explored the two-mile stretch of Soho Road in Birmingham – the site of some 30 religious centres – documenting and celebrating the rich diversity of religions that co-exist there, and the reality and intensity of their different lifestyles. I lived with and visited the different religious communities, including Thai, Sri Lankan and Vietnamese Buddhists, Rastafarians, the Jesus Army evangelical Christians, Sikhs, Catholic nuns and Hare Krishnas. The lively bus journeys along Soho Road on a Sunday were always insightful. They took Christian individuals to church congregations meeting in a tent in the local park or a school gym hall. Converted Iranian evangelical Jesus Army members in multi-coloured camouflage print outfits could be found sitting next to large decorative hats adorning Jamaican born ladies. On the same bus I would hear Muslim girls sitting at the back talking loudly about the latest fashions of the veil, while I chatted to Hare Krishna devotees on their way to central Birmingham to distribute books.

Under Gods: Stories from the Soho Road is a result of my own journey along Soho Road. What I was aiming to do with this intimate documentation was to show the significance and influence of religious identity in the city and how belief transforms urban spaces from the ordinary to the extraordinary. Under Gods investigates the power of what the people on the street believe their religion to be rather than what is prescribed by religious leaders or by the texts, as faiths are interpreted differently within each context of encounter between persons, places and objects. As a South Asian female Anglican priest said:

On Soho Road people are conscious of their faith rather than where they came from. People used to say ‘Oh I am from Bangladesh, Pakistan, West Indies or Poland.’ Now people say ‘I am a Muslim, I am a Sikh, I am a Baptist, I am a Catholic; this is my identity.’

At a time when religion can breed unnecessary fear and prejudice through misunderstanding, I hope that Under Gods reveals and celebrates the power of faith to form identity and to unify communities in contemporary inner-city life.

Hare Krishna book distribution outside a parish church – a Brazilian-born Hare Krishna devotee hands out flyers on a December morning and invites people for dinner at the Soho Road temple. At the age of twenty he left his native Brazil to preach about Krishna throughout Europe. © Liz Hingley

The Premier League – Muslim children in the backyard of their terraced house. Their formal Islamic dress is only worn for their daily after-school mosque class. The eldest boy checks the football results in the local paper; his sister speaks with their neighbour, a Jehovah’s Witness, over the fence. © Liz Hingley

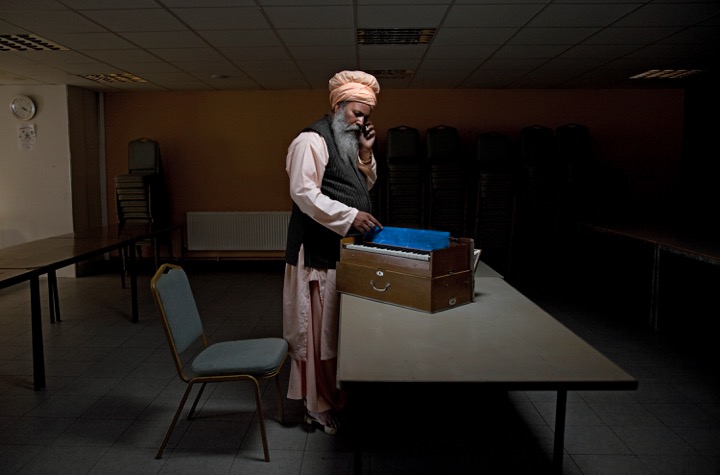

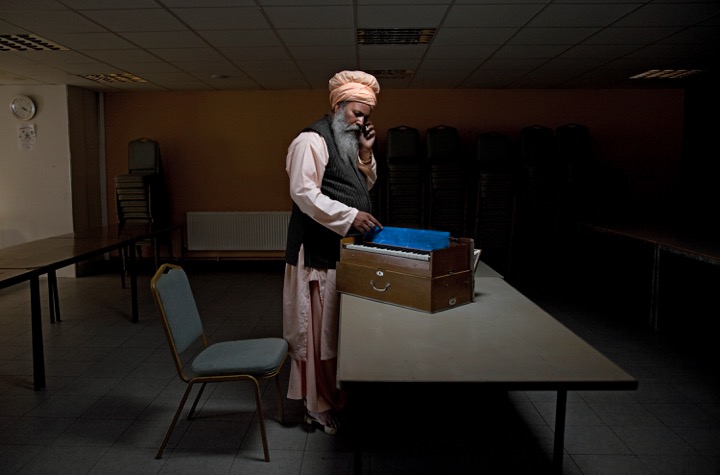

The visitor from India – a Sikh priest visits a Gurdwara on Soho Road. He regularly receives calls on his mobile phone from contacts in India. He speaks no English. © Liz Hingley

The biannual baptisms are an important occasion for the primarily black congregation at Cannon Street Baptists. During the service the baptism pool is uncovered and the pastor, supporter and person to be baptised enter into the water. © Liz Hingley

Minba Chair, Pakistani mosque – a terraced house converted into a Pakistani mosque. The Minba chair, a replica of that used by Muhammad, was made by the Sikh carpenters down the road. © Liz Hingley

A wedding party eats in Nanak Nishkam Gurdwara, the largest and wealthiest of five Gurdwaras on Soho Road. The temple bustles twenty-four hours a day with visitors praying and women making food in the vast kitchens, which distribute hundreds of free langarunga meals. © Liz Hingley

Old age and poor health means Mrs Little is no longer able to attend the church of St Andrews on Soho Road. The Anglican priest celebrates communion in her front room every week with friends from the church. © Liz Hingley

Liz Hingley is a British photographer and anthropologist whose work bridges academic scholarship and artistic practice. She is currently an Honorary Research Fellow of the Department of Theology and Religion at the University of Birmingham. Under Gods, the project on which this blog is based, may be viewed on her site.

18 October, 2017

The Moss family on the porch of their house in Kingston, Jamaica: Dirrell and Vera Moss with Carmen (9), Erroll (7) Lorna (5), Elaine (2) and Annette (3). The family was planning to emigrate to England, where Mr Moss, a printer by trade, would have heard about job opportunities, and where they hoped to begin a new life. The American government had limited the numbers of Caribbean migrants allowed into the United States in 1952, thereby increasing the amount of immigration to Britain.