The art studio as a ‘room to breathe’

Room to Breathe at the Migration Museum takes visitors on an immersive journey through a series of interconnected rooms, revealing the multi-layered experience of migrants and refugees arriving in a new country. Intimate personal stories are brought to life through audio recordings of oral histories as visitors go through the different rooms. At the centre of the gallery is the ‘Room to Create’, a space conceived as an art studio, which will be occupied by a succession of artists, each on a monthly residency. These artists have been invited to make the studio their own, displaying previous art projects while creating new artwork.

The first artist in residence and the curator of this art studio is Dima Karout, a visual artist and art educator originally from Syria, but who has lived in several countries before arriving and settling in London. In her journey from Syria to Britain via France, California, and Quebec, art has been a constant source of reflection and engagement for Dima.

This blog has been written as a series of questions and answers, with Assunta Nicolini (gallery supervisor at the Migration Museum) asking the questions and Dima and Sue McAlpine, one of the Migration Museum’s curators, answering them.

Assunta: Dima, could you gives us some background to your collaboration with the Migration Museum in ‘Room to Breathe / Create’?

Dima: My appreciation of the Migration Museum goes back to when I moved to London and visited their previous exhibitions. The first time I stepped into the Museum, it all felt very familiar. Some of the elements they presented reminded me of my own work – the suspended canvas, the personal stories, and the collective truth. I loved the slogan ‘All Our Stories’, and its sense of inclusiveness. We’ve been in conversation ever since. I met Sophie first, the Museum’s director, then Sue, one of its curators, and I showed her some of my installation artwork. Both she and Sophie were very welcoming and positive. This current exhibition, Room to Breathe, was a perfect opportunity for us to collaborate. I was thrilled to be invited to be the artist and curator in residence for the exhibition, and to add my vision to this project by designing the concept and overseeing the art studio space and the residency programme.

A ‘room to breathe’ is a metaphor that relates to a lot in my life. My art studio gives me a peaceful space to reflect on conflicts bigger than me, and to create. And the museum curators were aware of the importance of art in a time of displacement, in an artist’s quest for identity and meaning, and in their life in general. This space, as we designed it, gives artists from migrant backgrounds a platform to share their work, interact with visitors and tell their story in their own way. It is a space for them to represent themselves: this was very important for me. We will welcome a new artist from a migrant background every month until June, when I will work with all the artists to curate a final group exhibition.

I am very excited about this collaboration and grateful to be working with socially engaged people. It is important (and visitors’ feedback and reactions confirm this) to change the narrative about Syrians, to work with them and present them in a different light – as artists, educators, travellers – and to show that there is more to a Syrian person than the ugliness of war. I am glad to be part of this process.

Assunta: As the first artist and also the curator in residence at Room to Breathe, what is your vision and approach for the Art Studio?

Dima: As a curator, I wanted the room to reflect an authentic art studio. The artists are invited to display their artwork, handwritten notes, their own books, art tools and materials, etc. The space is personal, intimate and true to the artist’s own life and practice. But most important for me was to fully respect the invited artists’ freedom and to allow them to decide for themselves what their room to breathe would look like. We selected these artists from an open call we launched online, and every month sees a new display of the work and universe of a talented migrant artist. It’s really exciting that it shows there isn’t one way to design this space.

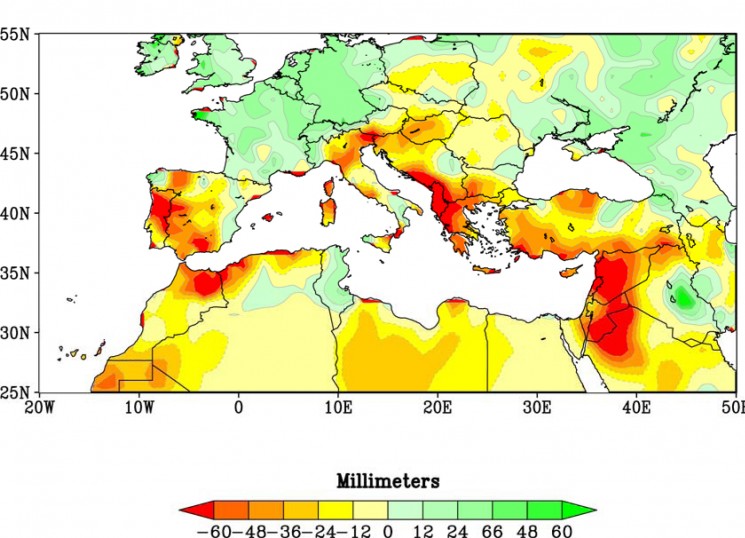

During my residency as an artist, I share pieces from different projects I’ve worked on over the years and exhibited in Damascus, Leipzig, Paris, Montreal and London. Visitors can go on a journey with me, see a photo for a set I designed for The Shroud Maker, a play shown at RADA last May, read some of visitors’ contributions to my installation Boarding Pass at Shakespeare’s Globe last June, follow my travels by reading fragments of my Travelling Souls project, and get to know me better by browsing my books, learning about the friends, artists and writers who inspired me, etc.

Visitors discovering aspects of Dima’s journey in her art studio at the Migration Museum. The large photo on the left is “Hope in Damascus”. © Rudy Hajjar

In addition to all that, I am present in the space most of the time, interacting with visitors. I approached the art studio as an educational space that brings art closer to everyone. I offered hands-on art workshops, and free printing sessions and I designed a participatory installation in which visitors were invited to sit in the art studio on a large table equipped with tools and materials and to create a piece of art reflecting on Human Bridges, and add it to the growing installation.

Assunta: How have visitors reacted to your work and participatory installation at the Migration Museum?

Dima: Visitors have been very moved by the intimacy of the work. They have taken the time to read and discover fragments of the different projects I shared: the struggle with the Syrian passport, being prisoner in your own self, the endless war, and home being more than a physical place . . . I left a livre d’or (a gold book) in my art studio and asked people to write the sentence that moved them the most. Everyone reacted in their own way, but a lot of people wrote the main sentence behind my The Tunnel installation, which I had handwritten in charcoal on the wall: ‘There is no black and white in the Syrian conflict, only shades of grey and too much red.’ Others wrote that, when they read my text The Prisoner (about someone who invented another self), it was the first time they’d realised how hard it was to be reminded of the conflict every day. Many Syrians who visited told me they connected deeply with a sentence from it: ‘You are tired from discussing your burning home.’

Dima Karout’s livre d’or (on the table), Syrian self-portrait and “The Tunnel” (on the wall), in her art studio at the Migration Museum. © Rudy Hajjar

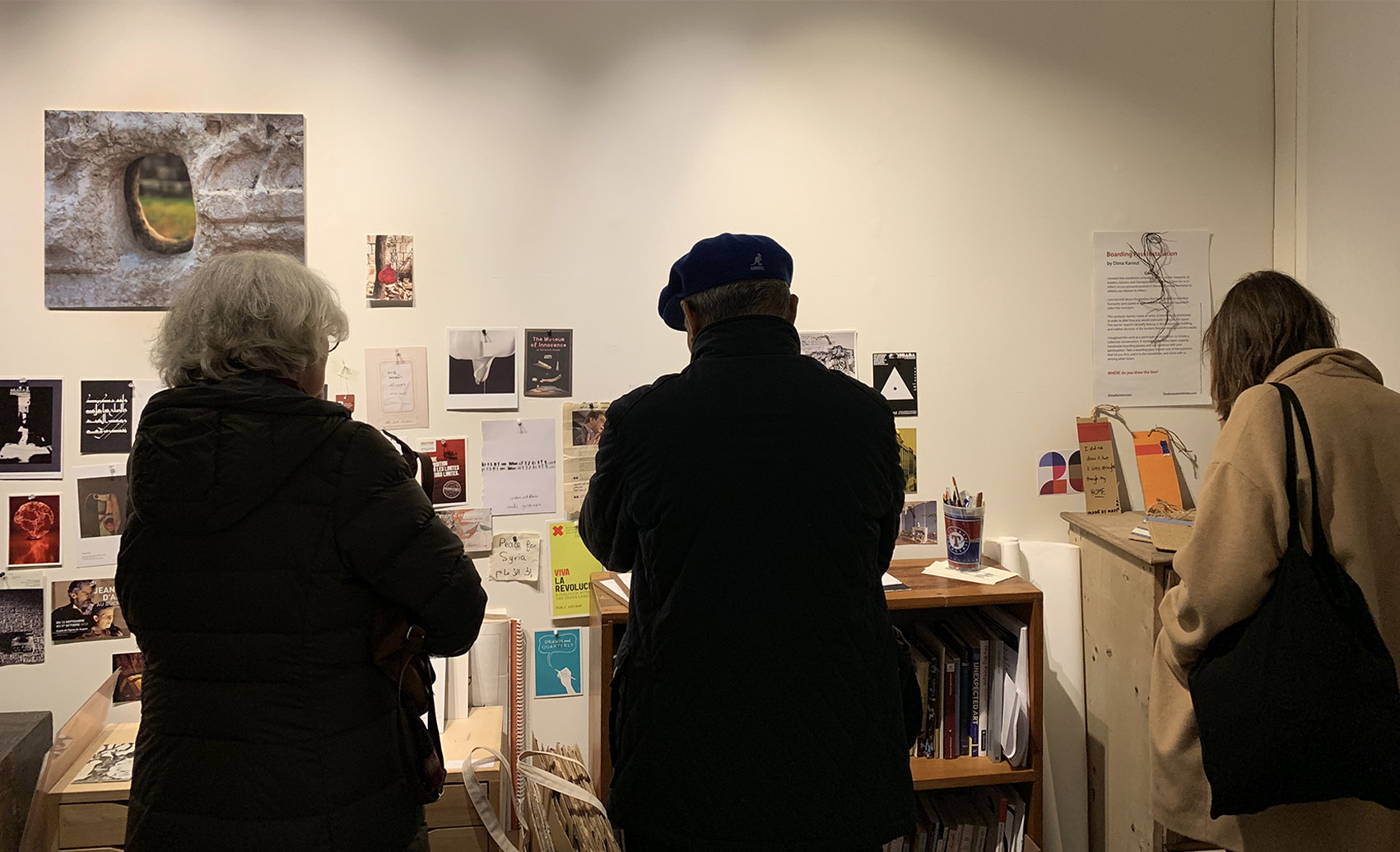

My favourite corner, which I wanted people to take with them from the visit, was the Human Bridges project: ten art objects and ten texts telling fragments of friendship stories, of the human bridges that me and nine Syrian artist friends were able to build and sustain over the years. The introduction to the project reads: ‘We all met at the fine art university of Damascus, sometime around the year 2000. We came from very different backgrounds, but art brought us together. Today, we have all lost our home, we live in different cities around the world, but a fine line of friendship built through art survived and is virtually crossing continents. Our Human Bridges symbolise the power of art over conflict.’

I also designed the Arabic word jesser (it means ‘bridge’) inspired by the calligraphic style Kufi Murabba’ and asked people to be inspired by its minimalist design to create their own bridge, using the table I set up in the art studio with tools and materials, and to add their signed artwork to the installation. Visitors from all ages and backgrounds, school and university groups, all expressed a connection with this project, and told me that they had been very moved by its honesty and simplicity. The installation wall is full with people’s bridges!

A workshop in Dima Karout’s art studio at the Migration Museum. © Rudy Hajjar

Assunta: To what extent does your origin and background as a Syrian influence your art?

Dima: This is a very intriguing question that I’ve been reflecting on a lot lately, specially after the war. My art reflects who I am in many different ways. I was born and raised in Damascus, Syria. I saw the world from this perspective when I grew up. But, since 2005, I’ve been travelling: I studied my masters in contemporary art in Paris, creative writing in Montreal. I got interested in curating contemporary art, and I followed an online certificate in curatorial studies based in Berlin, with international participants. I’ve discovered ideas, cultures and met extraordinary humans on my journey. My identity has evolved and continues to evolve. My art today reflects the new person I’ve become, who absorbed all these new experiences and listened. As much as I miss my younger, lighter self, I can’t possibly say I am still the same young Syrian girl who left Syria long ago. And this is what I am trying to reflect on through We Are Made of People and Places, the new work I am researching during my residency at the Migration Museum.

Dima Karout (centre) in front of her project “We Are Made of People and Places” in her art studio at the Migration Museum. © Rudy Hajjar

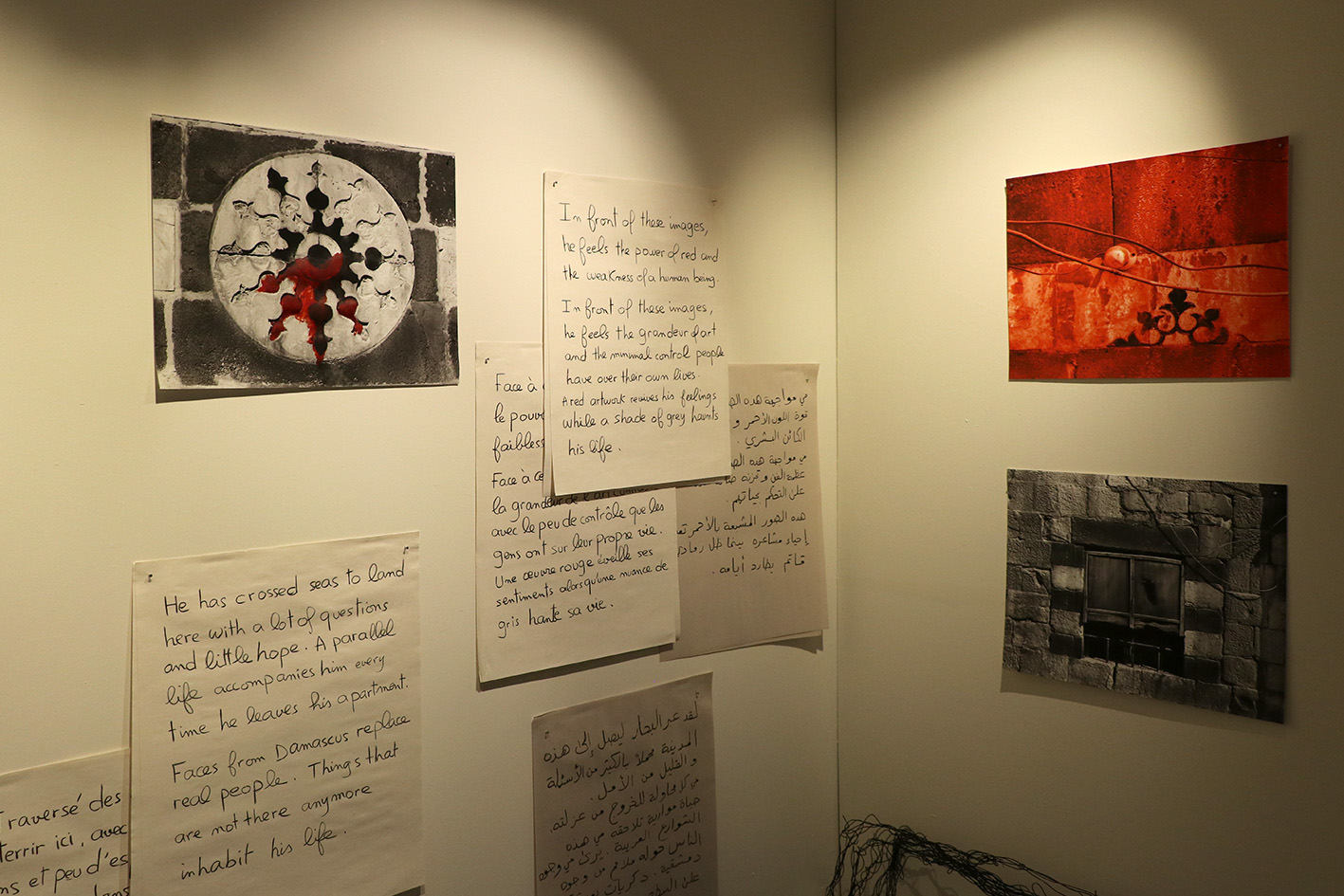

On the other hand, it is impossible for me to accept this forced disconnection from my roots. I am very affected by the Syrian conflict, and my art in the last few years has been too. After receiving my Canadian passport, I wrote that ‘You can travel everywhere, but you can’t visit Damascus. You have become a prisoner of the world’. Every Syrian is trying to survive the war in their own way; I created many artworks to cope with it. The Tunnel, one of the artworks that I presented in Montreal in 2016, is on display at Room to Breathe now; it tells the thoughts of a Syrian refugee who survived an explosion and arrived in a new country in a wheelchair. One piece reads: ‘Do you want to die as a whole or to live as a half? He chose life.’ Last year, I was tired from the division between Syrians and looking to create something that might reunite us all. I created the Syrian self-portrait. It’s based on a photo of an abandoned home that I took in old Damascus in 2011 during my last visit before the war, and features a strong façade with two windows, which I transformed into grey tones and then added red ink to. It represents the human behind the wall – and us Syrians, trying to look fine, to function in the societies we live in, hiding behind a strong façade, but bleeding from the inside.

Dima Karout hanging her display of “We Are Made . . . ” in her art studio at the Migration Museum. © Rudy Hajjar

Assunta: How would you define the main advantages and challenges of being an artist–curator?

Dima: I love both. For more than 15 years I have been creating art and also curating art exhibitions and cultural events in different cities around the world. I have worked with a lot of artists and art students from different backgrounds and, whenever I am trying to present someone else’s work, I think of the artist first. I aim to preserve the uniqueness of their journey while trying, if I am working on a group show, to create a narrative between all participants. It is very challenging to find this balance, but I think that being an artist myself helps me understand the artist’s side better.

The advantages are that I understand the uniqueness of every artist, the validity of their demands, and I always try to listen. There is a sense of fragility about artists that I try to protect when I curate group exhibitions, because I went through this journey myself.

My experience with curators is different. It is sometimes very challenging when you are the only artist on the team. The curators focus on presenting the whole exhibition, sometimes working on ‘exhibiting the exhibition’, whereas the artist wants to exhibit their individual work.

I am going to be working closely with the artists invited into the art studio: Habib Sadat, The New Art Studio, Ceyda Oskay, Shorsh Saleh and Belén L Yáñez; we are going to brainstorm and try to understand each other. I aim to assemble our creativity and forces around the final group show we want to launch in June, and to curate a unique experience for all of us and for visitors.

Assunta: Sue, as curator at the Migration Museum, what was your vision for the art-studio space?

Sue: When my fellow curator, Aditi Anand, and I were discussing which rooms we would make in our exhibition exploring stories of resilience and survival in the experience of migrants, the art studio was one of the very first we came up with. We had both seen first hand in the Calais refugee camp the power of art, music and theatre to raise people up from the despair of that notorious place. We met the volunteers who were providing the means for the people there to explore their creativity, and we met those who were benefiting from it. In an earlier exhibition, Call Me By My Name, we displayed some of the art made in the camp and told the stories of those who had made it. Much later I found out from one of the artists whose work we displayed that the opportunity to show his work in the country he was trying to reach had given him hope and strength to keep going and the knowledge that he was being recognised as an artist. He is one of the artists we have invited to be resident in the art studio.

One of my main aims as a curator is to allow people the opportunity to have their voices heard and to tell their stories in the way they would want them to be heard, to give them a platform to show their work – whether this is playing music, cooking food or presenting art, photography, drama or poetry. My role as a curator is to make this happen with as little interference from myself as is possible and practical. So our vision for the art studio was to give artists a studio space to make their own, to furnish as they wished, a space to be creative: to make art, display it, sell it and to share their ideas among visitors and other artists. We were happy for it to be a messy, painty, inspiring space where our artists could feel completely at home. We felt this was especially good for migrant and refugee artists, who are still struggling to keep going in this country and for whom having an art studio, even for a short time, is a real luxury. We loved the idea of providing a space for an exhibition within an exhibition. We liked the idea of it being a changing space, inspiring for our repeat visitors and for the exciting development of the bigger exhibition. Above all, we wanted to demonstrate that the need to be creative touches us all and is a vital and enriching part of our humanity.

Assunta: How would you define your experience of working with artist–curator Dima Karout? What are your thoughts on her artwork and her art studio (Dima’s work is on display at the Museum until Monday 3 December)?

Sue: When I first met Dima, I felt strongly she would be a wonderful artist to present work in the studio. As we learnt more about each other, it became clear that Dima was the perfect person to form a collaboration with and it gradually emerged that she should take on a bigger role as artist–curator of the studio, which fitted perfectly with my idea of the curator who can step back and give others an opportunity to have a say in how the exhibition unfolds. Our discussions were sometimes heated and often confrontational but we have come to a beautiful understanding and a wonderful outcome in the way Dima has made the studio her own and interacted with her visitors. I respect and value Dima’s knowledge of what makes an artist tick and especially her sensitivity and understanding of the artist who is also an immigrant.

“The Tunnel” in Dima Karout’s art studio in the Migration Museum. © Rudy Hajjar

I have watched visitors in Dima’s studio looking at her artwork and have seen them silently witnessing her journey, her pain and her vision for a better world. I saw my daughter crying when she looked at Dima’s images of a lost Damascus. I have seen visitors making their own interpretations of the concept of Dima’s bridge between people and places and hanging them up on the participatory, inclusive space that Dima has made. I have listened to the conversations that visitors have had with her, not just about her art, but about her life, her past friends, her family, her sorrow for her war-torn country and her tentative steps towards building its future. Her studio is a powerful place to be in. Of course, it proves that making art for Dima is a lifeline. But there is more to it than that – it shows that art connects us to our own journeys through experiencing the journey of the artist. We need art to make sense of things and we need artists to express what is going on in our hearts and heads. We need to be artists ourselves.