21 December, 2017

The festive season is upon us. According to experts commenting on the subject in magazines and newspapers, it could equally be called the arguing season. A friend in an early Christmas party bemoaned the arrival of her in-laws, bringing with them different opinions on Brexit and other political issues that, sooner or later, led to uncomfortably heated confrontations.

And just two days ago, what started as a really interesting discussion in our house – on why so many men failed to recognise that rape and wolf-whistling were on the same continuum, on the way in which power relationships skewed jokes and banter, on whether it was ever acceptable to use racial identity to comic effect – morphed into one of those confrontational exchanges from which at times it feels there’s no coming back.

© Scott and Borgman

And it got me thinking, in an end-of-year valedictory fashion, why it was that discussions, arguments and debates these days so quickly became polarised, and the position taken by the opposing individuals so firmly entrenched. (And is it just ‘these days’? Was it always like this?) What starts out as an exchange of views transmutes into an exchange of fire, and people’s positions end up ludicrously exaggerated – as Hella Eckardt’s recent blog illustrated, in relation to Roman Britain. People at either end of the spectrum insist on the absolute truth of their position with a strident vehemence that doesn’t represent the reality – which is that all of us, bar the most extreme fanatics, recognise the possibility of alternative positions even when firmly convinced of our own. But rather than examine the evidence, listen to whether the other speaker brings something new to the debate that might cause us to reconsider, it suddenly seems more important at any cost to win this argument, to prove that our position is right and the other’s wrong.

Is this failure to discuss and the associated need to win spawned by the structure of our institutions? The adversarial position is hard-wired into our legal system, for example, and also into Parliament (at least, certainly the House of Commons); it used to, and may still, be at the heart of university research and debate; and it’s of course the basis of all sporting activity. It’s clearly not unique to the UK (the US displays it in spades) but is it uniquely Anglo-Saxon, or European, or Western? Are there countries and cultures where winning an argument is less important than hearing what everyone has to say?

These questions lie at the heart of what we are attempting with the Migration Museum. If our concern was to win the argument (whatever that might be) or show other people the error of their ways, we would, rightly, be doomed to failure and unworthy of support. But what we are wanting to do is to create a space where people can debate issues of paramount importance without automatically taking up tired and predictable positions and seeing who can shout the loudest. Our strapline – all our stories – was chosen to reflect both the fact that if you scratch the surface of anyone’s family history in Britain, you will find a migration story, but also, crucially, the recognition that everyone has a say in this matter and all have a right to be listened to, even if some might find their views unacceptable.

It’s not a new year’s resolution, because it’s been the nub of what we’ve been doing since the beginning, but listening and allowing the spectrum of opinions to be heard without it all descending into the weary Twitterati scrimmage of rancour and animosity – that’s what we’ll continue to do in 2018. With Brexit, Trump and other factors casting their divisive, polarising shadow, it seems more important than ever. So, if you’re raising a glass over this festive period, here’s to listening, not fighting.

To all our readers and followers, have a really good break over the festive period, and see you again in the New Year.

12 October, 2017

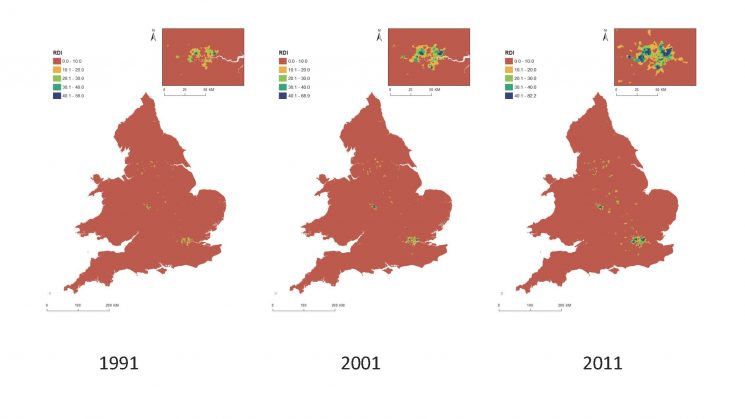

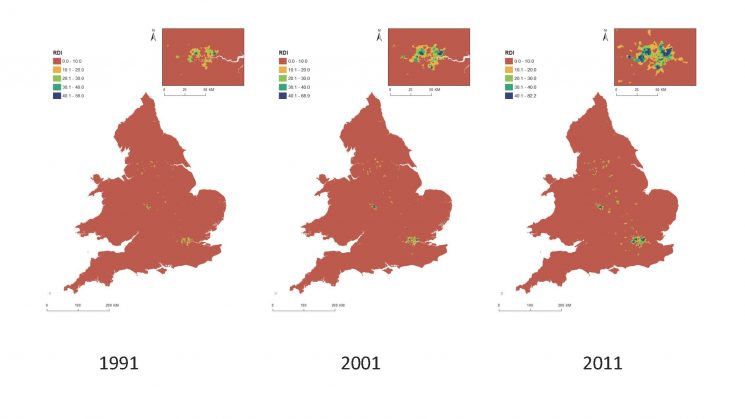

As Britain’s towns and cities become increasingly diverse, teaching about multicultural becomes more and more important. ‘Minority’ groups are found no longer only in large (post-) industrial cities like Manchester or Birmingham but also in smaller urban centres like Boston and Peterborough. The maps show census data which reflects these changes, with the green and blue shadings indicating more diverse areas. The changes from the 1991 map to the 2011 map reveal more areas becoming diverse, and already diverse areas – such as parts of London – becoming even more diverse.

Source: Gemma Catney (2016) ‘The Changing Geographies of Ethnic Diversity in England and Wales, 1991–2011’, Population, Space and Place, Volume 22, Issue 8, 750–65.

The geographies of multiculture have changed and are continually changing, so that all areas, and the schools they contain, need to think about how people engage with cultural diversity and difference. As part of the Migration Museum Project’s Call Me By My Name exhibition in 2016, we ran a teaching workshop to help students think about their own identity and how they identify and relate to others in their daily lives. Our workshop took place in the space of the exhibition, surrounded by photographs, artwork and artefacts that brought into the room personal experiences of migration, refugee camps, loss of home and loved ones and experiences of moving to the UK. Haunting the space were the fake ‘life’ jackets used by migrants and found on beaches, exhibits counting relatives lost in perilous sea crossings and the vulnerability of lives lived in camps, at borders and on the margins of societies.

We began the workshop with Year 8 students by asking them to walk around the room. When we clapped, they had to form into self-selecting groups of four or five (i.e with no intervention from ourselves) and we asked them to draw around both their hands on A4 sheets of plain paper. They then wrote on their left-hand outline words that describe how they see themselves and on their right-hand outline words that they think other people would use to describe them. Next, they were asked to talk in their groups about the words they had used to describe each hand, and how they felt about the words others might use to describe them. After a few minutes of these group discussions, in the course of which we mingled and chatted, a few students stood up to talk about their hand drawings and labelling.

The aim was to open up questions of cultural identity and to think how inadequate words and categories are for capturing complex and shifting identities. One person, for example, labelled themselves as Somalian, from Milton Keynes, and moving from Sweden – and even then they were aware that these labels didn’t really capture who they were but were ways they used to help others position them. When it came to how others might label them, however, they replied ‘African’ or ‘black’. In most cases, there were differences between how people identified themselves and how they thought others would identify them.

We asked the students why they sat with whom they did, because we were also interested in the ways in which groups form. One group of young men were largely of Ghanaian origin and were vocal and confident; other groups were a bit more mixed ethnically and nationally, with only one or two putting themselves forward as spokespeople.

The dynamics of the room were used as a way of thinking about the small-scale geographies of multiculture. While the school body was very mixed ethnically, like many classrooms across the UK, groups sometimes followed particular ethnic and national lines. Most students were used to using ethnic and racial labels like ‘white’ or ‘African’, but were equally aware that these were quite blunt categories which concealed lots of complexity and contradictions.

It is these same everyday ‘micro’-geographies that we explored in a research project called Living Multiculture: the new geographies of ethnic diversity and the changing formations of multiculture in England, which we conducted as part of a team led by Professor Sarah Neal.

Mural in Hackney, east London. ©Author’s own

The Living Multiculture project started from the reality of the changing geography of ethnic diversity in contemporary Britain – the patterns shown in the maps above. Places are changing, and we wanted to understand how people understand and live through these changes. We also wanted to examine ‘everyday’ encounters across ethnic difference against the background of the popular image, in the media and among many politicians, that multiculturalism in Britain had ‘failed’ – particularly post-BREXIT – and that cities are riven with segregated neighbourhoods and ethnic and racial tension. It was not that we wanted to turn a blind eye to very real conflicts, but to argue that, for many people, most of the time they rub along. Our main question was ‘How do people live and experience multiculture as part of their everyday lives?’

We studied this question through fieldwork in three areas, each of which represented a different aspect of Britain’s changing ethnic geography.

- Some cities that were already diverse are becoming ‘superdiverse’ with the arrival of new migrant groups. For this group, we chose the Borough of Hackney in London.

- Some ethnic groups that first settled in inner cities are now moving outwards, as their social and economic status improves. For this group, we studied the newly diverse suburb of Oadby in Leicestershire.

- As noted, some large towns and small cities are becoming diverse for the first time – for this, we chose Milton Keynes as an example.

You can find out more on our website and in a new book we have co-authored with the rest of the team, but some of the key findings are:

- We studied the places where people gather and mingle – cafes, parks, libraries and colleges. We found that these are important sites for people to be together in quite relaxed and informal ways, even though a lot of thinking and design goes into making them seem informal. For example, in the chain restaurants we studied, it was the informality of the fast-food model that enabled people to rub shoulders in easy ways.

- We also found that ‘things’ and places matter to these relationships. The design of internal college spaces or shopping malls all aided flows of people or encouraged mingling. Mundane things like park benches or car parks were all crucial for allowing people to encounter one another.

- But social skills were also important for living cultural difference. Managing the un/easiness of being thrown together in a room with us and being asked questions about identity involves considerable skills. One such skill students used was knowing how and when to joke with whom. Like some of our respondents, they knew that ethnic labels concealed as much as they revealed, and they could push the boundaries of these labels without generally causing offence. It was this knowing-ness about how to get along with diversity that came through in our workshop and which we explored in our various research contexts.

Drawing around your hands might seem playful, but it opens up a whole series of questions about the micro-geographies of multiculture.

Dr Katy Bennett is an Associate Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Leicester, where she works on questions of social and cultural geography, especially identity, emotion, home, community and multiculture. Professor Giles Mohan is at the Open University and works on international development and migration. Together they were part of a team headed by Professor Sarah Neal called Living Multiculture. Out of this project the team has just published a new book called Lived Experiences of Multiculture: The New Social and Spatial Relations of Diversity, details of which can be found here.

13 August, 2017

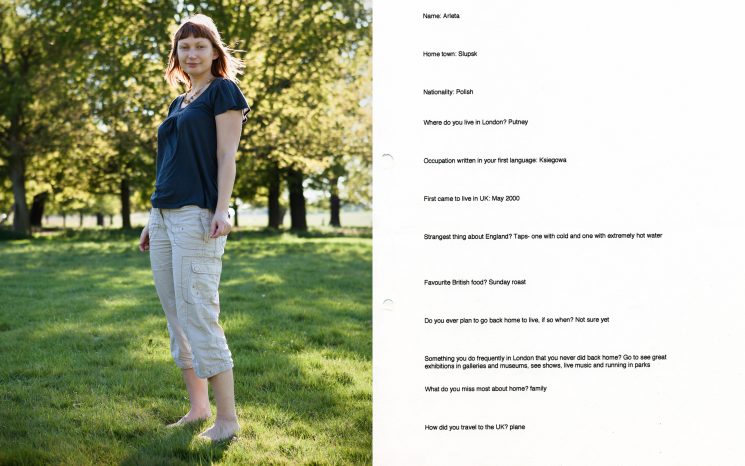

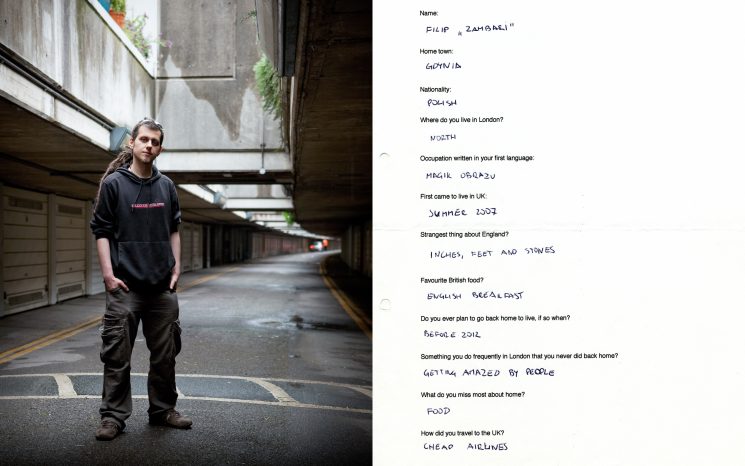

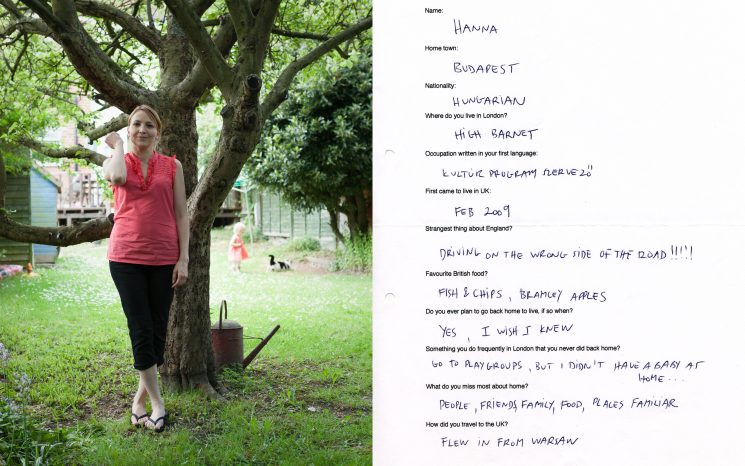

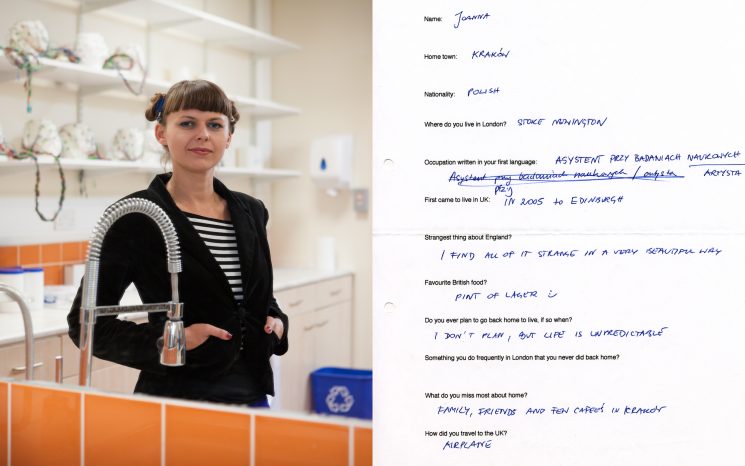

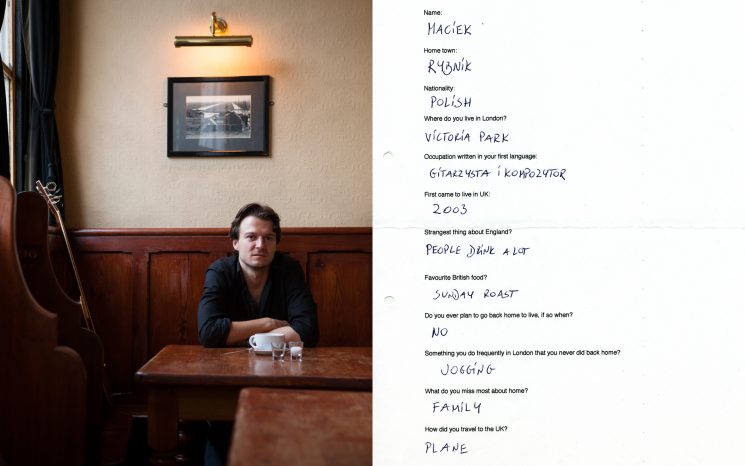

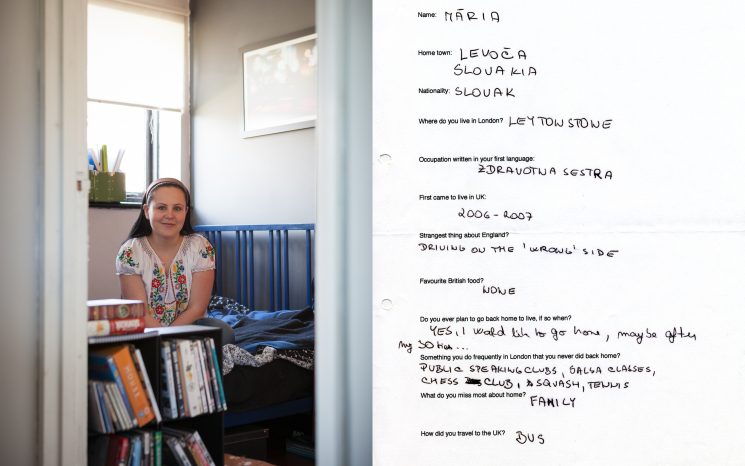

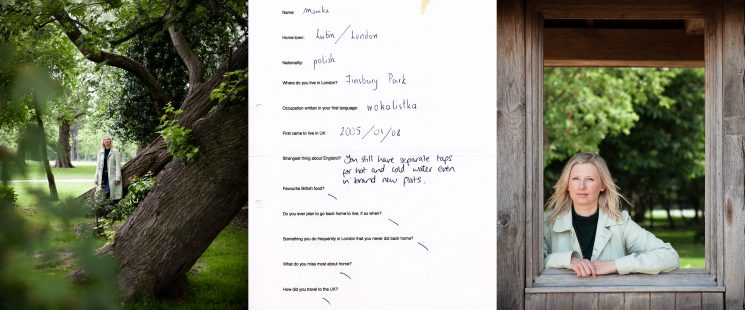

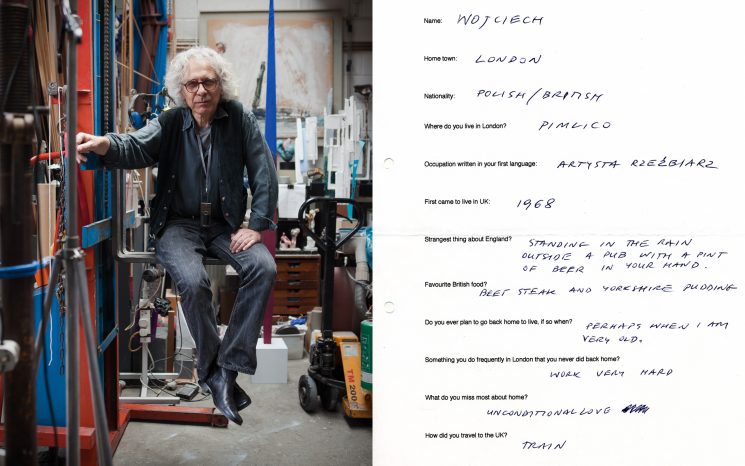

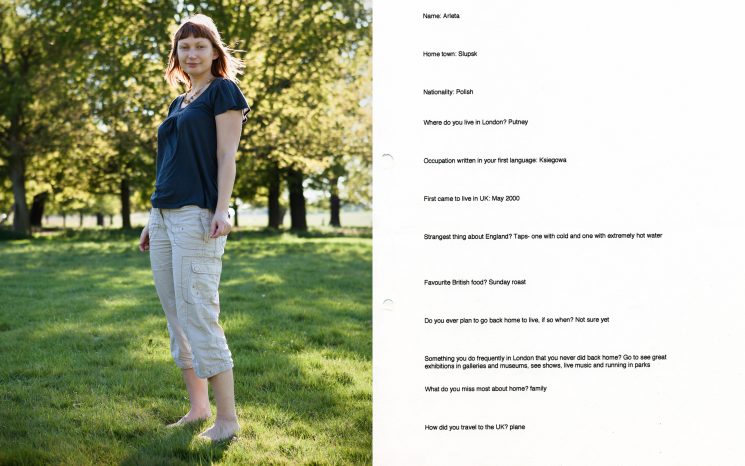

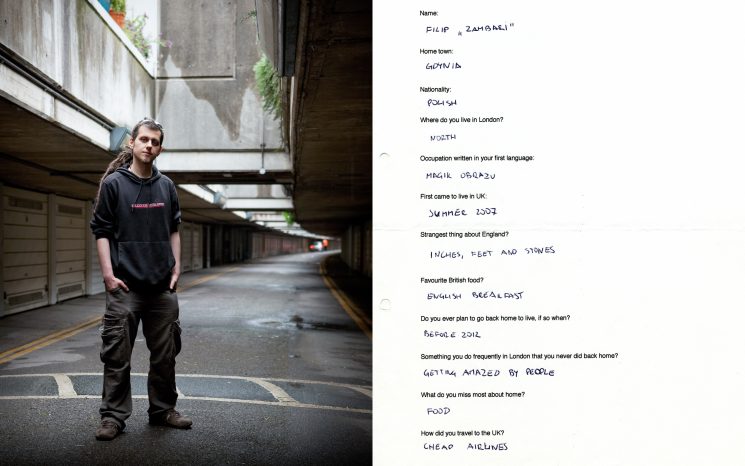

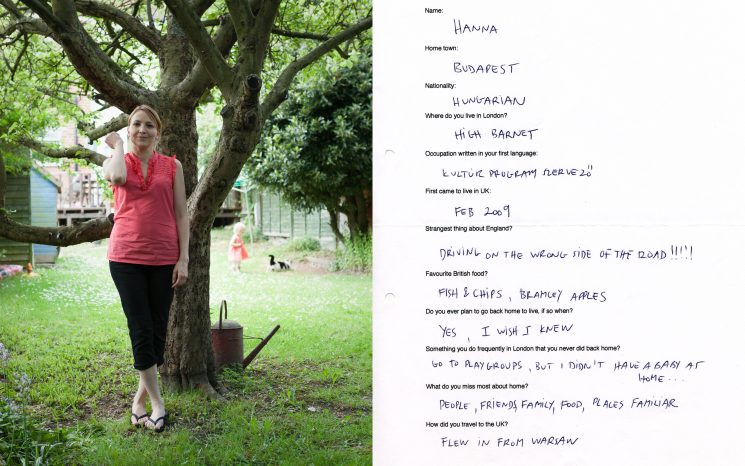

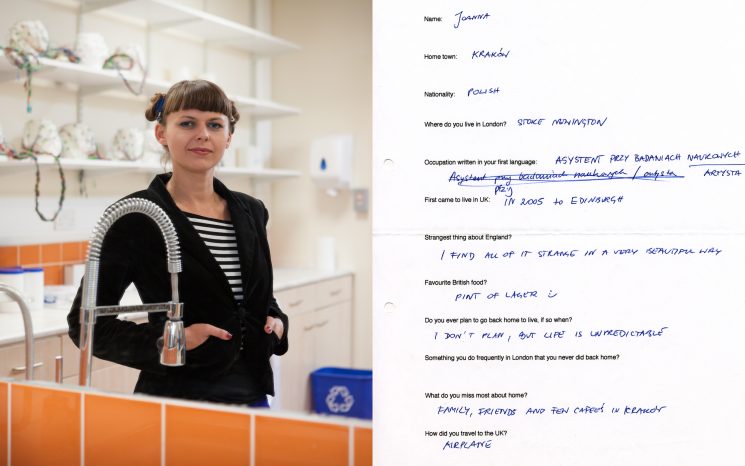

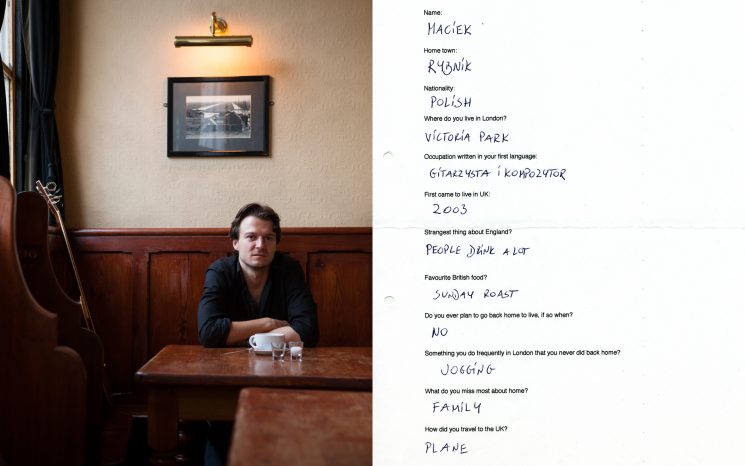

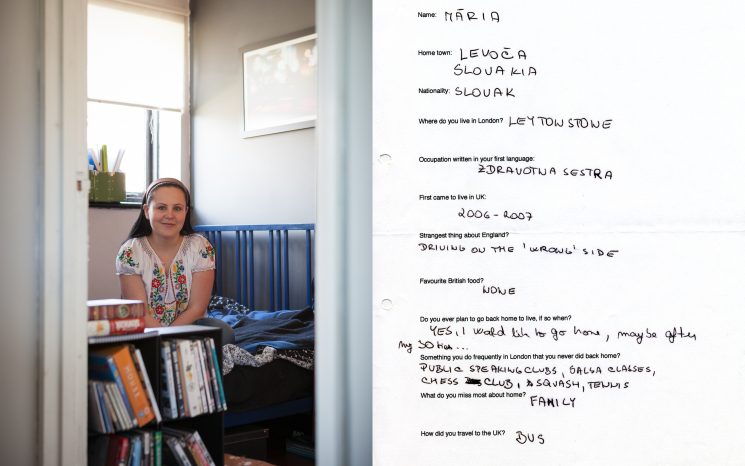

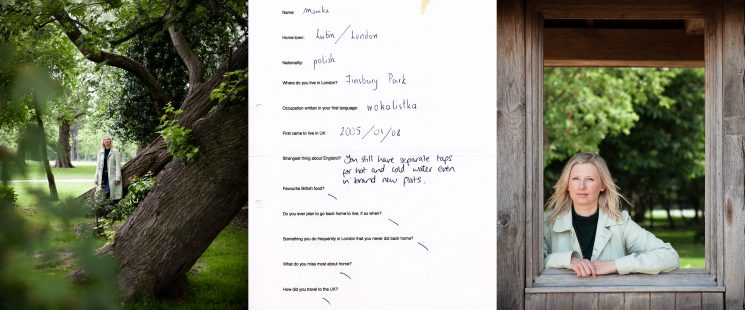

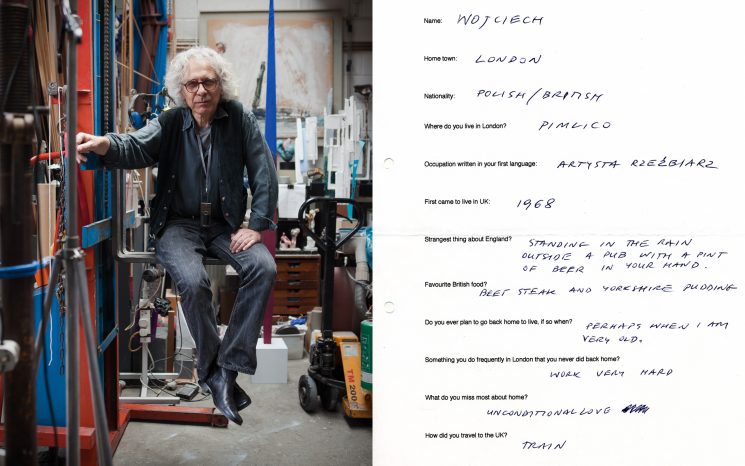

In 2010, Simon James took a series of photographs for an exhibition which he called Home, 2010. This was a series of portraits with handwritten answers to a questionnaire alongside the photos. The questionnaire asked the subjects of their photos a series of factual questions –name, home town, nationality, part of London they lived in, occupation, time of arrival in the UK, mode of transport to the UK – together with some that were more opinion-based: what did they find the strangest thing about England, what was their favourite British food, did they every plan to go back home to live (and, if so, when), what they did in London that they never did back home, and what they most missed about home. The portraits and the questionnaires can be viewed on Simon’s website.

Simon James‘s ‘Home, 2010’ exhibition, first shown as part of ‘Alien Nation: the art of blending in’, Great Western Studios, London. March–April, 2011.

In his notes to the exhibition, Simon framed the collection in this way:

‘One should not be an alien at all.’

George Mikes, How To Be An Alien (1946)

Mikes’s book highlights the absurd cultural contradictions between England and continental Europe. England is a nation of immigrants. Throughout history waves of immigrants have chosen London as their new home.

Ten of the twelve most recent accession nations to the EU have been eastern and central European countries. Citizens from these nations are entitled to work in the UK, but have limited access to benefits and social provision. Since 2004 there has been a noticeable increase in migration from these countries to the UK.

Many of these new arrivals have been met not only with scepticisim but sometimes also with hostility. They found a very different England from the one they had expected.

It is these people that you see in these photographs.

These beautifully constructed portraits hint at common experiences of migration: almost to a person, what the subjects most missed about home was family, friends and food. Similarly, despite a clearly critical position on British cuisine, there was general admiration for Sunday roasts, steak pie and those two other stalwarts of British eating: fish and chips (ours courtesy of the Portuguese) and pizza (our national Italian dish). And the things that they found strange about England and Britain held few surprises: driving on the ‘wrong’ side of the road, separate hot and cold water taps and, again, food.

Simon and the Migration Museum Project were in discussion again earlier this year, when the exhibition at Roast Restaurant in Borough Market was being planned. Reluctantly, we decided that his photos didn’t quite meet the criteria of that exhibition, but we ended up talking about a follow-up to Home, 2010, to see how the subjects’ answers to the questionnaire might have changed in the wake of the June 2016 referendum on the UK’s membership of the European Union. An e-mail was duly sent out to everyone he’d photographed, asking them to give their answers now to the opinion-type questions on the original questionnaire.

The people whose photographs appear in this blog answered the e-mail, and their answers are given here underneath the original photos of Simon’s 2010 exhibition. There’s nothing scientific about this ‘research’, of course, but the set of eight answers gives a sense of the mobility (or temporary nature) of migration – many subjects had gone on elsewhere or returned home (and we could speculate endlessly about the reasons the others didn’t answer the e-mail) – and a hint of a darkening mood since last June. Maciek, who in 2010 had said he had no plans to go home, now writes ‘Yes, very soon! If not Poland, then France/Italy’; Arleta, who previously wasn’t sure, is now thinking about it; Filip and Hanna have both left already (as they had said they would in 2010), Hanna now citing that the thing she finds strangest about England is ‘Brexit’. It would be interesting to track down more ‘before’ and ‘after’ stories of this kind and to revisit these eight subjects in a year or two’s time: it is often a useful corrective to have anecdotal and human evidence set against the statistical findings trotted out by competing positions on Britain’s departure from the EU.

Arleta, and her responses in 2010. © Simon James

Arleta, 2017 responses

- What job do you do in London?

Accountant day time/landscape photographer at weekends.

- Strangest thing about England?

Two separate taps – one with very cold water and other with boiling hot water.

- Do you ever plan to go back home to live? If so, when?

I’m thinking about it but I haven’t made up my mind yet.

- What do you miss most about home?

Mushroom picking in autumn.

Filip, and his responses in 2010. © Simon James

Filip, 2017 responses

- What job do you do in London?

Graphics design and video post-production for a production house in Camden.

- Strangest thing about England?

Separate taps for hot and cold water. Calling normal taps ‘continental’; in general, your insistence on calling stuff ‘continental’ felt strange, but it makes more sense now since you voted for Brexit.

- Do you ever plan to go back home to live? If so, when?

I did come back already actually, back in 2012.

- What do you miss most about home?

London was great, top of the world and all, but it was also very competitive. At home I don’t have to prove who I am, there’s less possibility but also less stress; at home I’ve got more time to learn new stuff and I have more room to make mistakes (which are essential if I want to make progress).

On the other hand:

I think what I miss most about London is the architecture, mainly the brutalist style that I am in love with, starting from well-known estates like the Barbican or the Southbank, I just kept stumbling on some totally amazing pieces of architecture on my cycle journeys through the city like the Heygate estate or Alexandra Road Estate, which I picked for Simon to take a picture of me, but literally dozens of other amazing spaces that just kept forcing me to stop and gaze for a while each time I took a different route home.

That would be one thing that I never did back home – call my girlfriend and say, ‘Honey I’ll be home a bit later, I just discovered this another awesome building and I positively need to see how it looks from another side before I move on.’

Hanna, and her responses in 2010. © Simon James

Hanna, 2017 responses

- What job do you do in London?

I no longer live in London. My last job was working in marketing for a broadcaster, mostly looking after their Eastern European business.

- Strangest thing about England?

Brexit.

- Do you ever plan to go back home to live? If so, when?

I have since moved to Warsaw, Poland (so not home), and now I live in Southern California. I do plan to move back home for retirement though.

- What do you miss most about home?

Familiarity. Family and friends. Language.

Joanna, and her responses in 2010. © Simon James

Joanna, 2017 responses

- Strangest thing about England?

Separate taps for hot and cold water; hand washing can turn into a nightmare.

- Do you ever plan to go back home to live? If so, when?

No plans at the moment.

- What do you miss most about home?

Family and friends and my mum’s cooking.

Macíek, and his responses in 2010. © Simon James

Macíek, 2017 responses

- What job do you do in London?

Musician/composer/guitarist.

- Strangest thing about England?

Separate cold and hot water taps!

- Do you ever plan to go back home to live? If so, when?

Yes, very soon! If not Poland, then France/Italy.

Māria, and her responses in 2010. © Simon James

Māria, 2017 responses

- What job do you do in London?

Property investor.

- Strangest thing about England?

Weather and food, English manners.

- Do you ever plan to go back home to live? If so, when?

No, but I’m considering other options such as Asia or Dubai (temporarily).

- What do you miss most about home?

Our large quiet garden, better weather, cheaper restaurants and services.

Monika, and her responses in 2010. © Simon James

Monika, 2017 responses

- What job do you do in London?

Singer, songwriter, singing teacher.

- Strangest thing about England?

Food: sandwiches with chips, beans on toast.

- Do you ever plan to go back home to live? If so, when?

Not at the moment, but we will see how it goes.

- What do you miss most about home?

Family and friends.

- Something you do frequently in London that you never did back home?

Going to pubs – we haven’t got pubs in Poland.

Wojciech, and his responses in 2010. © Simon James

Wojciech, 2017 responses

- What job do you do in London?

I am an artist. My jobs are my projects and also the services I perform for galleries and collectors in the care and condition of art collections.

- Strangest thing about England?

That the country of such great traditions – cultural, technological, politically liberal – can sink so low as it has done recently in adopting euro-sceptic point of view reserved until now to a narrow group of MPs such as John Redwood, Bill Cash and a Daily Mail lobby.

- Do you ever plan to go back home to live? If so, when?

I am rooted to deeply now and my mother country is suffering from the very same illiberal affliction. It would have to get a lot worse before I would do that but ‘Events, dear boy, events’, as Macmillan once had said, are unpredictable.

- What do you miss most about home?

Familiar touchstones – such as sights, well-spoken words, theatre, warmth of family and friends

- Something you do frequently in London that you never did back home?

Listening to BBC Radio3, my favourite radio station, closely followed by John Humphries and James McNaughtie – the great news men from Radio 4.

There is more information about Simon James, and more of his photographs, on his website:

www.shotbyjam.com

19 July, 2017

How long do you have to live somewhere before you are accepted as belonging there? A friend moved to a village in Devon 30 years ago and is now leader of the parish council. But she regularly finds her proposals or decisions challenged by another council member, who invariably begins his sarcastic intervention, ‘Well, as someone whose family have lived in this village for only the last 500 years . . . ’ My friend ruefully reflects that it will take her somewhere between 30 and 500 years to be accepted into the community in which she has chosen to raise her family.

Defining national identity is an equally tricky undertaking, whether for a person or a country. Post-referendum – and even before, as the UK citizenship test demonstrates – trying to work out what it means to be British is a bit of a national preoccupation, and one that British politicians routinely come unstuck on. It’s something that at least three distinguished friends of the Migration Museum Project (Robert Tombs, Robert Winder and Afua Hirsch)* have written about or are currently writing about – and they are not alone: type ‘Britishness’ into the search engine of Amazon and you’ll come up with just short of 100 books on the subject.

Defining national identity on a personal level is no less complicated. The passport you own is one factor, but many people who hold a British passport self-identify as any number of things (English, Welsh, Scottish, Irish, European, Jewish, Muslim, Black) before they identify as British – we are way beyond the Norman Tebbit test of which national cricket team you support.

And then, as Johanna Konta has reason to understand this Wimbledon, and numerous other sportspeople before her (Mo Farah, Greg Rusedski, all the way back to Basil D’Oliveira), being famous doesn’t bring you immunity from other people’s speculation about your identity. You may call yourself British, you may have a British passport, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that some journalists, and others, accept you as British.

Johanna Konta, the latest in a long line of British sportspeople to be questioned about their ‘Britishness’. © Telegraph

National identity is hardly homogeneous either – last year’s referendum and this year’s general election have shown how many different kinds of Britishness and Briton there are in this country. And this isn’t a new phenomenon. Let us take another of our distinguished friends, Sir Konrad Schiemann, who was orphaned in Germany and brought over to this country by his uncle, Werner von Simson: their experience was played out more than 70 years ago but will still reflect that of many people who are in the process of making the United Kingdom their home.

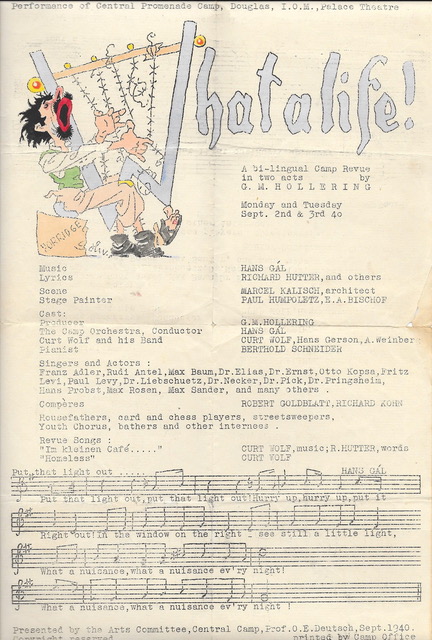

Werner had married an English woman in 1938 and came to England a year later, in June 1939, for the birth of their child in June 1939. He was in this country when war broke out and, having seen what was happening in his country of birth, Germany, and wanting no longer to be part of it, he stayed here. This didn’t stop him being rounded up along with other ‘enemy aliens’ living in Britain when Churchill gave his (in)famous order to ‘collar the lot’. Irrespective of how long you had lived in the country, or what your political allegiances might be, you were gathered together by ‘national identity’ and, in Werner’s case, sent to spend the war on the Isle of Man. The same thing happened to Konrad’s wife’s mother and grandfather – the musicologist O E Deutsch – who had fled Austria.

On the Isle of Man, German might have been a unifying language among the internees, but German Jews found themselves rubbing shoulders with Nazi sympathisers, communists with fascists.

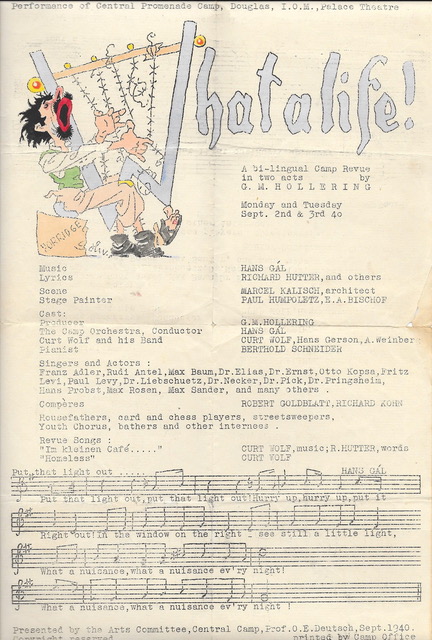

The programme notes for ‘What a Life!’, a camp revue put on in Douglas on the Isle of Man in September 1940.

(O E Deutsch’s story is one we have touched on before. While on the Isle of Man, he was involved in the production of What a Life!, a bi-lingual review that was put on in Douglas in September 1940. One of the songs from the review was performed by Norbert Meyn at the launch of our Germans in Britain exhibition in 2014.)

Werner brought his nephew, Konrad, to this country in the aftermath of the war. Konrad, born in Germany in 1937, lost both parents in the final stages of the war, his father being shot by partisans in Italy just months before VE day and dying shortly after, and his mother dying of a broken heart in Germany’s ravaged capital, Berlin, to which she had returned in the hope of being reunited with her husband.

Berlin in 1945 lay mostly in ruins. Konrad Schiemann and his mother were living in 64 Eichenallee, Westend, a house that was, as his uncle Werner wrote, ‘intact – it must be one of the very few houses which are’. © Monovisions

The circumstances of the newly orphaned Konrad’s removal to this country are conveyed in a series of letters, the first written in German by the 8-year-old Konrad himself (my translation):

10 Dez 1945. Liebe Tante Janni, ich werde Dir eine traurige Nachricht geben, dass Mutti krank geworden ist, weil wir ein Telegramm gekriegt haben, das lautet: das Papi grosses Pech haben musste, in den letzten Tagen von Partisanen überfallen zu werden. Er wurde am 30.4.45 verwundet und ist dann durch Versagen des Herzens am 3.5.45 im Teillazarett D in der Nähe von Padua gestorben (Grab Nr.178). Viele Grüße an Bettina, Andreas und Tante Hilda Dein Konrad.

10 Dec 1945. Dear Aunty Janni, I am going to give you some sad news. Mummy has become ill because we have received a telegram telling us that Papa had the really bad luck to be attacked by partisans in the last days [of the war]. He was wounded on 30 April 1945 and died on 3 May 1945 in the Teillazarett (hospital) D near Padua following a heart attack (grave number 178). All good wishes to Bettina, Andreas and Aunty Hilda. Your Konrad

Konrad’s mother, Beate, died on 10 January 1946, and Werner then volunteered to adopt the young orphan himself and bring him up in England as a member of his family, an arrangement in line with Beate’s wishes. In response to a letter from him, Werner’s father, agreeing with his suggestion, had this to say about the process of naturalisation (my translation):

Säge, 14 March 1946

My dear old Werner

I’d like next to say that I fully and unconditionally agree with everything you say. Now, the matter of your own naturalisation: I’ve always held the position, because of my own considerable experience of living abroad, that people who have come to feel really at home in another country can become essential promoters of good relations and rapprochement between the country of their birth and their adopted country only if they take on the nationality of their adopted country. Taking that further, even before these last twelve years, and especially before these last seven, I would always – since you are kind enough to value my agreement – have been happy about your becoming English. After these last years, in which sadly I have completely lost any connection (at least for the moment) with my fellow countrymen and women and can’t for now imagine – given the way in which they have behaved – how I will ever rediscover it, I approve of your actions all the more, an approval which is mixed with a slight sense of envy. What you have to say about Konrad’s future also meets with my full approval. On reading Ätchen’s will [Ätchen is Beate, Konrad’s mother], I said at once that for Konrad to be accepted into an English house and an English school would be possible only if he were himself to be brought up completely as an Englishman. That would have been desirable even in friendlier times; now it seems to me imperative. Ätchen’s wishes can be met only if the child were either to be placed under your guardianship in a German boarding school or allowed to become English as soon as possible.

For many immigrants, becoming English as soon as possible involves changing your family name to make it less ‘foreign’. With people from German-speaking countries, this process involves what Professor Rudiger Goering (previously Rüdiger Göring) in a lecture on George Frideric Handel (previously Georg Friedrich Händel) wryly referred to as ‘the inevitable shedding of umlauts’ and other German-specific sounds, such as changing ‘mann’ to ‘man’. Rather famously, one hundred years ago this week (17 July 1917) the Saxe-Coburg und Gotha family decided to change its name to the more English ‘Windsor’. Under the conditions of his mother’s will, Konrad kept his German name, an omission that Quentin Hogg (Lord Hailsham – a Conservative grandee and one of the longest-serving British politicians) mentioned on meeting Werner when Konrad was being sworn in as a judge. When Hailsham commented that Konrad had never ‘anglicised’ his name, Werner responded, ‘We’re not the royal family, you know.’

Sir Konrad Schiemann, barrister and judge and distinguished friend of the Migration Museum Project. He served the Court of Appeal and was also a member of the Court of Justice of the European Union.

Reflecting on his upbringing earlier this year, in an Inner Temple lecture on ‘What is Europe?’, Konrad Schiemann (who went on to become a barrister and judge, serving both the Court of Appeal and the European Court of Justice) confesses to be ‘one of the foreign-born workers and pensioners whose presence in this country clearly many find disturbing’. On paper, of course, he is the quintessence of Britishness – direct grant school in Birmingham, national service, Cambridge University degree, barrister, knighted in 1986 – and yet in a bizarre twist of events, and despite his having lived in this country for over 70 years, his British identity has come to be challenged since the referendum. As he said in the same Inner Temple debate:

Fortunately, throughout my time in this country, I have never felt myself hated – until, that is, the debates around the recent European referendum, when to my astonishment I found myself for the first time treated by some with whom I used to have a perfectly friendly relationship as an enemy of the people. I know German Jews who were equally astonished when the same thing happened to them in the 1930s.

In the months and years that follow, as we renegotiate our relationship with Europe and the wider world, those of us who call ourselves British – whether we have lived here for 30 years or for 500 – might do well to consider what it might mean to our national identity to define it so narrowly as to rule out so many who have – in sport, culture, commerce, law, politics and day-to-day living – enriched it beyond possible calculation.

* Robert Tombs, who gave our annual lecture in 2015, is the author of The English and their History, which is in many respects an attempt to provide a historical explanation of how we got to be the nation we now are. On 27 July, Robert Winder, whose book Bloody Foreigners was the early inspiration for the Migration Museum Project, publishes The Last Wolf: The hidden springs of Englishness, a book that attempts to identify the ingredients of the English national character. And early next year there is a new book by Afua Hirsch, Brit(ish): Why we need to talk about race, a book that also explores the identity crisis at the heart of Britain today, but from a racial perspective.