26 August, 2015

A profile of Charlie Phillips, photographer and contributor to 100 Images of Migration

Charlie Phillips had never planned to be a photographer. When, in the standard career interview towards the end of his time at school, the youth employment officer asked him what he wanted to be, Charlie answered ‘A naval architect’. Even now, his eyes fire up more when he’s talking about ships or the Middle Passage (‘my favourite passion’) than about almost anything, except maybe Britain’s renunciation of its maritime past – one of the derelictions of duty he can’t quite forgive his adoptive country for. And, in fact, his passions are many: don’t get him started about Captain Bligh and the role that breadfruit played in the mutiny on the Bounty, or about Captain (as he then was) Nelson, who met his wife, the daughter of a plantation owner, in his service in Antigua – or, rather, do, because he talks about both with the eye-glistening enthusiasm that he brings to the many subjects that fascinate him.

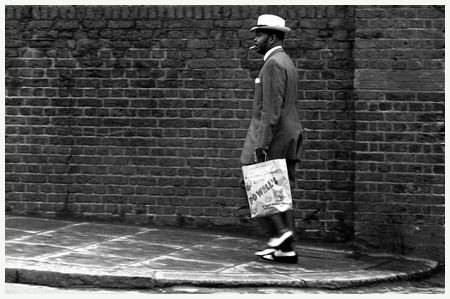

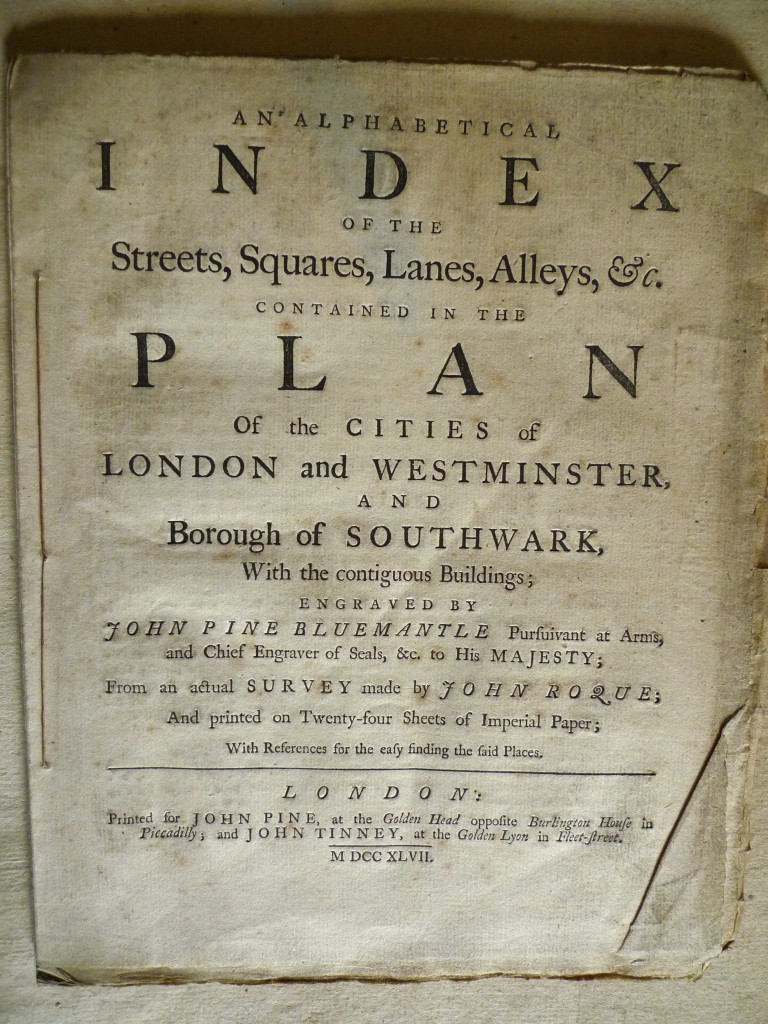

Man in zoot suit, Great Western Road, 1968. One of the sharp dressers of the period. © Charlie Phillips/ww.akehurstcreativemanagement.com

But we’re here to talk about Charlie’s photographs, here being the Tabernacle in Notting Hill Gate, which Charlie has been visiting for a long time and where, seated outside in the bitter summer cold, he is warmly greeted by everyone going into and out of the building. His photographic career began by accident. A visiting GI left a Kodak Retina camera behind and Charlie instinctively took to it, photographing the people and places of Notting Hill, moving between 200 and 400 ASA black-and-white film and printing the results of his shoots in the family bathroom when his parents had gone to bed. Entirely self-taught, he continued to take photographs on and off for the next 30–40 years until the arrival of the digital camera put paid to his career (Charlie says that he ‘refused’ to make the move from analogue – stamping the act as the political statement he feels all our actions are). Sadly, all too few of his photographs have survived a life that started in Jamaica and which, from London, careened between Ireland, France, Italy, Switzerland, before pitching Charlie back in London.

Schoolgirls, Lancaster Road, 1970. © Charlie Phillips/ww.akehurstcreativemanagement.com

London had never been the long-term plan, either at the start of his stay there or with his return 25-odd years later. Charlie had left his native Jamaica in 1956, sailing to Britain on the Reina del Pacifico (he has perfect recall for all the ships he has been on or seen). The idea was to stay in London for something like five years and then to go on somewhere else, most probably America, which is where other members of his family went. Instead, after the ill-fated interview with the youth employment officer had quashed Charlie’s dreams of naval architecture (the officer had suggested he should try the postal service, the RAF or London Transport instead), he spent three years in the merchant navy, working mostly in catering. He had always been interested in running away (he cites Norman Rockwell’s painting ‘The Runaway’ as a source of inspiration) and when he left the navy he did just that, travelling to Paris and becoming embroiled in the events of 1968 – ‘the start of my revolutionary, my bohemian years’ – before hitch-hiking further south to Italy, where he spent a further ten years.

The Reina del Pacifico, the ship on which Charlie arrived in England.

Charlie feels his career as a photographer really took off only when he left England and, with slight bitterness, lists a number of other black British artists who had to go abroad to make their name. In Italy he worked for commercial gain as a paperazzo, living in a commune but hob-nobbing with the artistic cool set of the time. That’s him in the notorious banquet scene in Federico Fellini’s Satyricon, in which a whole cow is split open to reveal cooked meats inside – the only part of the film, I’m delighted to tell him, that I remember in vivid detail; he knew and admired Giorgio de Chirico and was respected and valued by the artists he associated with: ‘They called me “the black Cartier-Bresson, compared me to Fox Talbot and stuff’. And it was in Italy that he had his first major exhibition, in Milan. After a second, this time in Switzerland, he followed his heart back to London, where he has been based ever since and where he now spends his time tending his rose garden, looking after his tomato plants and trying yet again (this is now his eighth attempt) to read War and Peace.

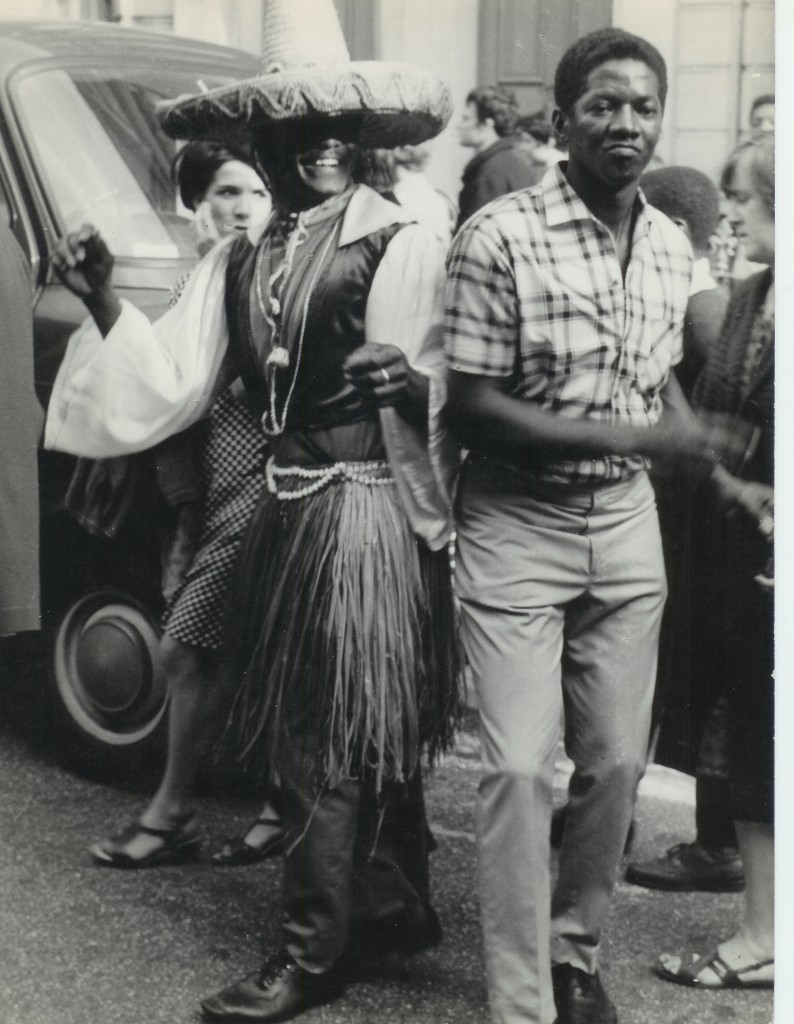

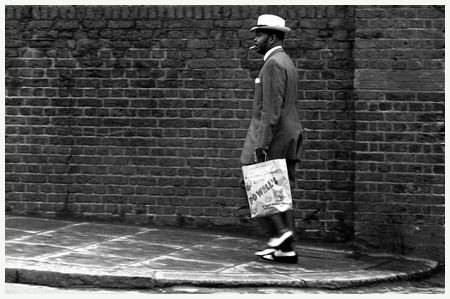

Ledbury Road, 1968. © Charlie Phillips/ww.akehurstcreativemanagement.com

Too few of Charlie’s photographs have survived his European peregrinations: you sense that Charlie was often too interested in the present to concern himself with archiving his past achievements. All the photographs he took of Jimi Hendrix, for example, were lost in Charlie’s mid-period movement from squat to squat. Indeed, his recent exhibition, How Great Thou Art, a collection documenting 50 years of African Caribbean funerals in London, came about when two other photographic professionals Charlie knew took on the task of sifting through some of his old boxes in an attempt to help him de-clutter his life. The exhibition itself was then crowdfunded through Kickstarter.

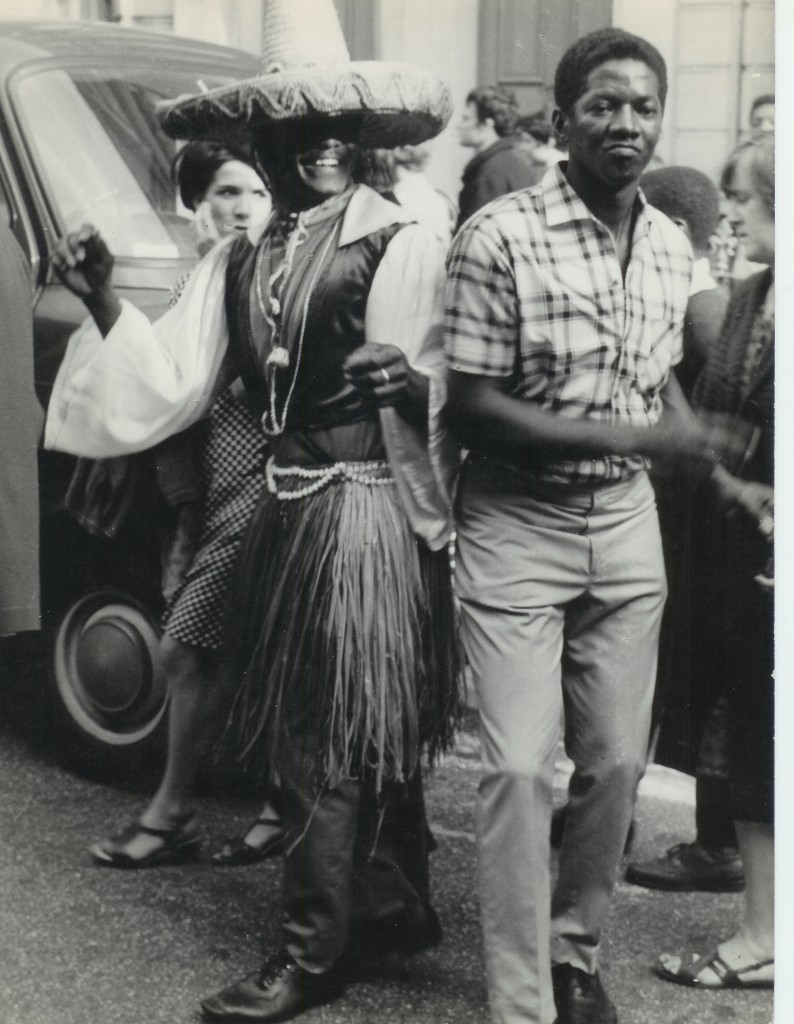

Jennifer, Jamaica Independence Day, 1962. © Charlie Phillips/ww.akehurstcreativemanagement.com

We will have to content ourselves, then, with the few remaining photographs that Charlie can lay his hands on. But these still have a tremulous power and an immediacy and presence that mock the intervening years. When schools and colleges visit our 100 Images of Migration exhibition, Charlie’s photos are always among those cited as the visitors’ favourites – many of the younger people are shocked at ‘Room to Let’ or captivated by ‘Notting Hill Couple’, aware about how powerful that image must have been at the time but conscious now of the open ease of the subjects’ pose, the classical simplicity of the composition.

Belatedly, Charlie is getting something of the recognition he deserves. The fact that this has arrived decades after he stopped taking photographs doesn’t seem cause for regret. In fact, don’t mention ‘regret’. Among the many things that Charlie still feels passionately angry about – the fact that the ‘Arts establishment’ has no interest in community artists, that ‘the bureaucrats have taken over the asylum’, that London feels, to him, culturally demoralised – is the banalisation of the Caribbean funerals that were the subject of his recent exhibition. ‘Do you know what the most frequently requested song is now, for the moment when the coffin goes into the grave?’ he asks indignantly. ‘When it used to be “How Great Thou Art”’ – and for a moment he goes off piste and intones the start to the hymn – ‘it’s now “My Way”. Can you believe?’

The funeral of Cassidy, a motor mechanic. Before his death Cassidy had asked not to have a hearse and so his coffin was taken to the cemetery on his employer’s Land Rover, in honour of his trade. © Charlie Phillips/ww.akehurstcreativemanagement.com

It turns out that Charlie always fancied himself as a singer, too, even wanted to be an opera singer at one time. He’s off to the opera this evening, as it happens. Not the Royal Opera House, of course (he refuses to go to the fat-cat palace it has become), nor to the ENO (purist and revolutionary at the same time, he dislikes its failure to stick to the original librettos), but to Opera Holland Park, as ever supporting the local, the community. ‘Still the old revolutionary,’ he says – though his major concern, he tells me in the few minutes we have left, is the inability of grandchildren to communicate with their grandparents. He feels that somewhere between the late 1970s and the 1990s a cultural gap grew that hasn’t yet been filled, one which is full of stories still to be told.

Notting Hill Couple, 1967 – one of Charlie Phillips’s photos in the ‘100 Images of Migration’ exhibition that always attracts intense interest from visitors. © Charlie Phillips/ww.akehurstcreativemanagement.com

He might be right. But his photographs have bridged that gap a long time ago, and continue to do so for every person who comes across them for the first time.

19 August, 2015

This guest blog by Mihir Bose, a distinguished friend of the Migration Museum Project, was written shortly after his visit to Adopting Britain, the exhibition at the Southbank Centre to which the Migration Museum Project has been a proud contributor.

Migration is always presented as a story of numbers. It goes as follows: that this is a small island, hordes of people are always wanting to come here for its riches, and it just cannot take any more.

I have been hearing this story ever since I arrived here in January 1969. At that time, of course, immigration meant coloured immigration. Now that nobody in Britain is racist, or nobody admits to being a racist, people who talk about this overcrowded island being swamped with marauding migrants seeking benefits go to great lengths to say it is not about race, just numbers. How a country should regulate migration is a legitimate subject to debate, of course, but this obsession with numbers means we have missed out on one central fact: that at the end of the day migration is about people, not numbers – it is a series of short stories about individuals who come with their customs, styles, cuisine, beliefs and ideas, and about their often very varied interaction with the host community.

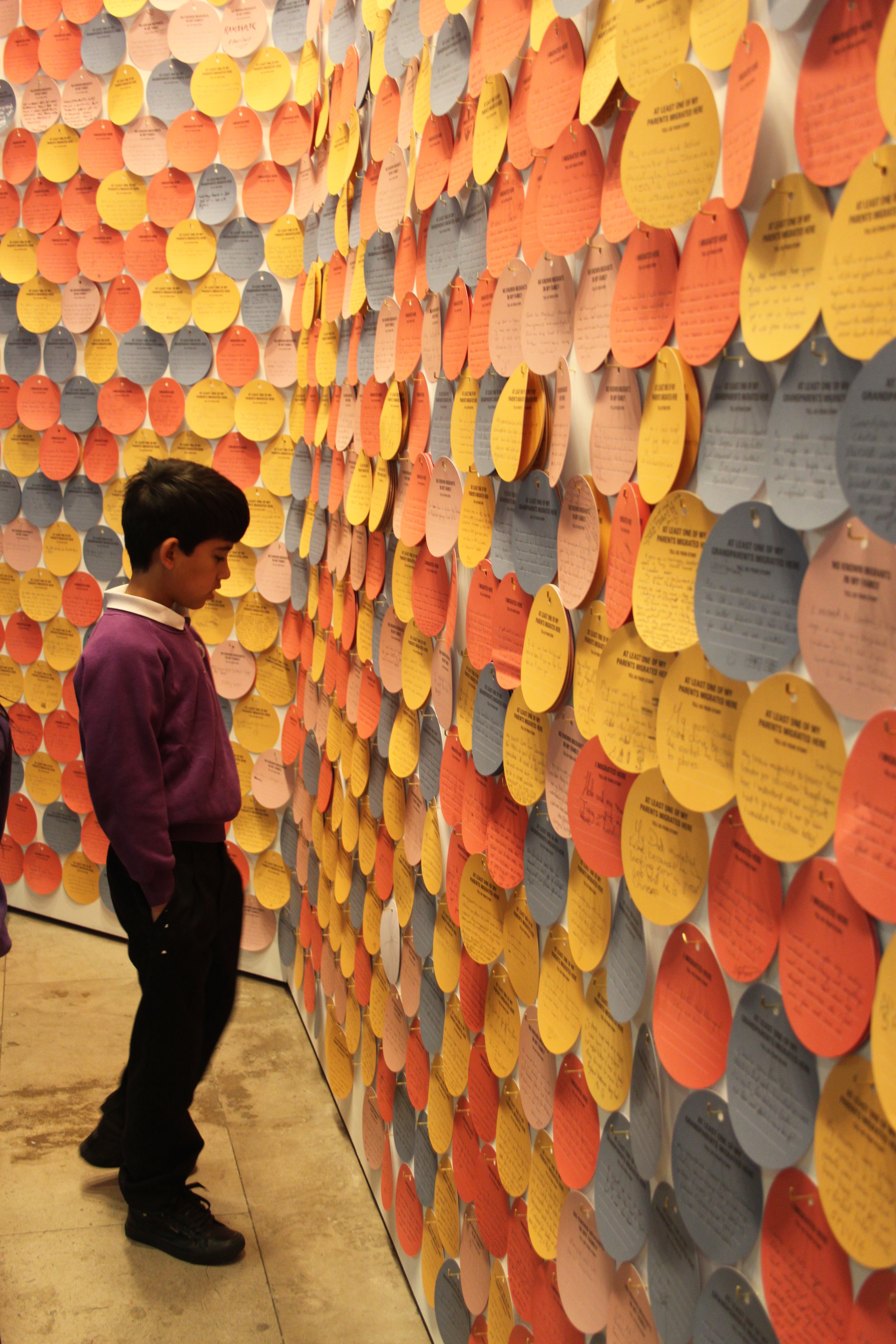

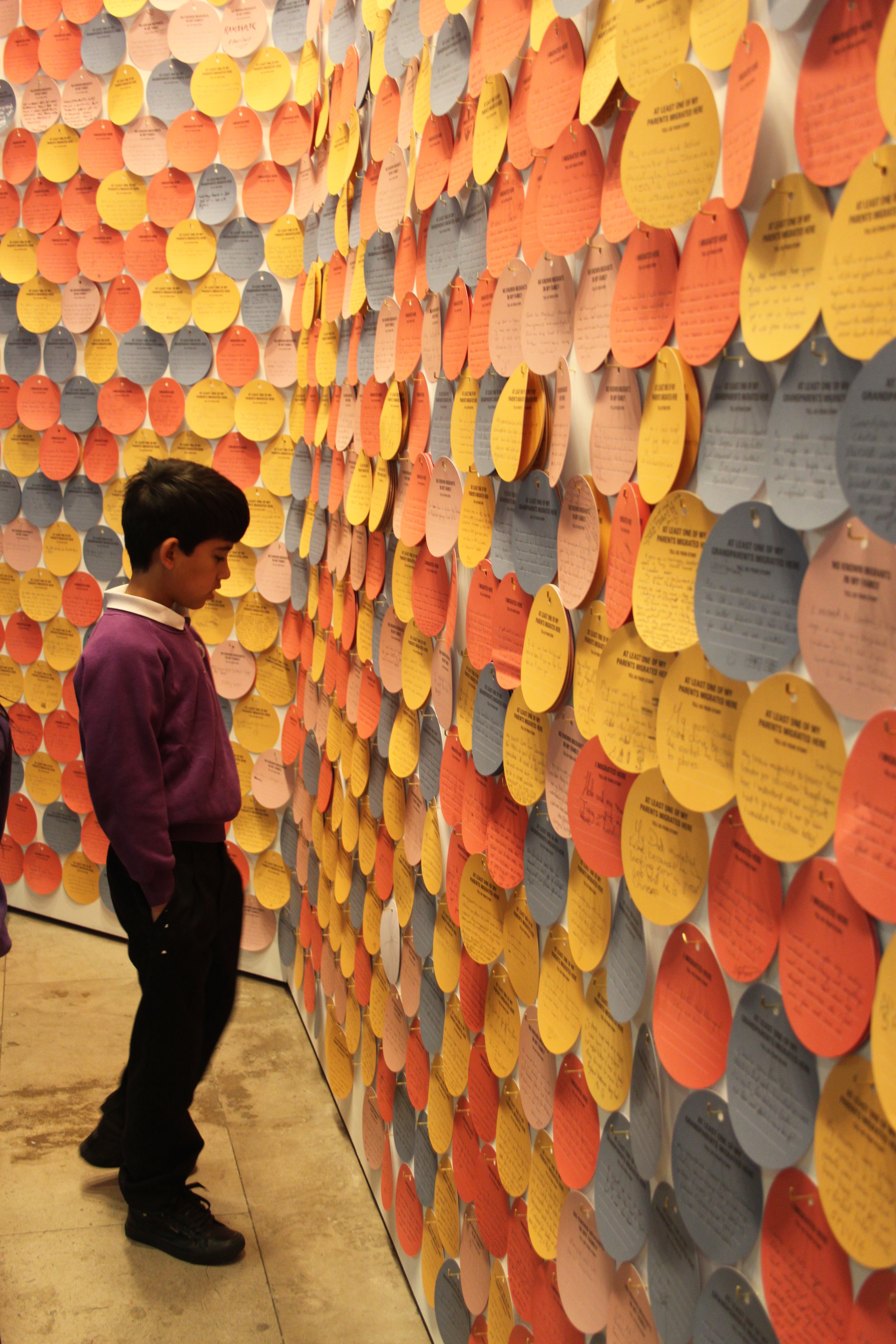

The starting point of the ‘Adopting Britain’ exhibition in the Spirit Level at the Royal Festival Hall, London. The exhibition, curated by the Southbank Centre and Counterpoint Arts, features many of the Migration Museum Project’s ‘100 Images of Migration’ and also its ‘Keepsakes’ project. This photo shows the starting point of the exhibition; it was taken a few days into the exhibition.

The same starting point to the exhibition, but several weeks later. The Southbank Centre printed 5,000 of the disks featured (colour coded depending on whether you migrated here from elsewhere, your parents did, your grandparents did, or nobody in your family did) – visitors are invited to fill them in before entering the exhibition.

And this is where the exhibition Adopting Britain: 70 Years of Migration, currently on show at the Southbank Centre, is so fascinating. Going round the exhibition was like a walk down memory lane for me. For example, there is a marvellous video which juxtaposes footage of immigrants from different countries with that of Enoch Powell delivering, and later reflecting on, his infamous ‘rivers of blood’ speech.

How could I forget Enoch? I arrived little more than six months after that speech. In it the Conservative MP forecast bloodshed and ruin as a result of coloured immigrants flooding into the country, and quoted a constituent telling him that ‘In this country in 15 or 20 years’ time the black man will have the whip hand over the white man’. Many believed Powell was right. What is more, just days before I arrived, Powell had had a famous television duel with David Frost. The confident expectation was that Frost, the Jeremy Paxman of his age, would nail Powell. In fact, it was Powell who got the better of Frost and made sure the debate about immigration was conducted on his own terms.

Enoch Powell, the Conservative MP for Wolverhampton South West (a seat he held from 1950 to 1974). A brilliant orator, he gave his infamous ‘rivers of blood’ speech in 1968 and was sacked from the cabinet as a result. Part of this speech is on display in ‘Adopting Britain’ in a video produced by students at the University of Leicester’s School of Museum Studies, where ‘100 Images of Migration’ was re-curated in 2014–15.

I was to realise how deeply he had influenced this country when, just over a decade later, I was returning home one dank winter evening from reporting a football match for The Sunday Times. I was taunted by young white football fans who were sharing my train carriage. They could not believe a ‘Paki’ like me was not managing the corner store and asked me what I thought of Powell – their taunting was followed by other football fans, who assaulted me. When I told them I thought Powell was a great Greek scholar, they found that difficult to believe. It was clear they only thought of him as the man who had first brought up the issue of coloured immigration. As it happened, I had a very pleasant interaction with Powell, persuading him to review a book for a magazine I edited.

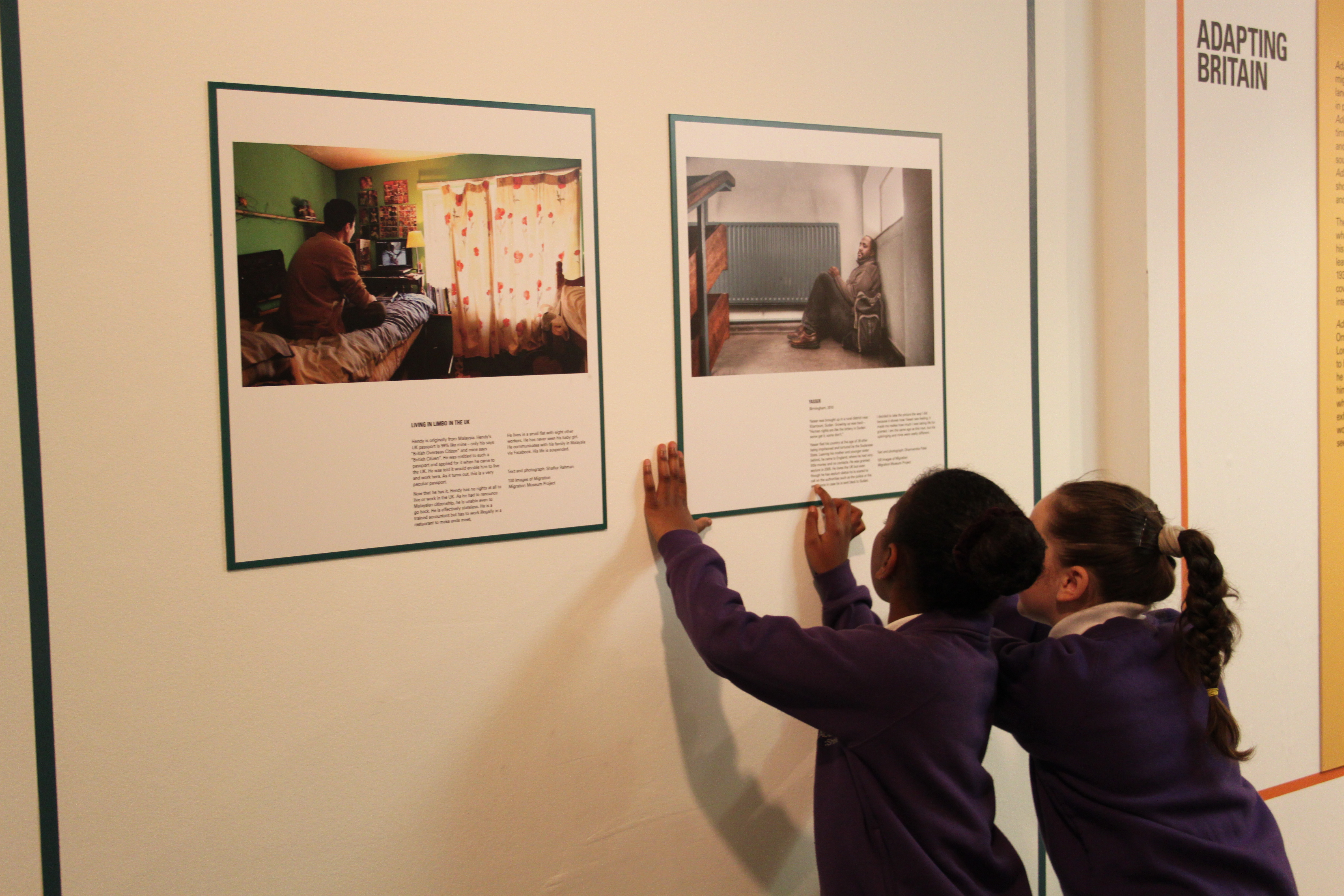

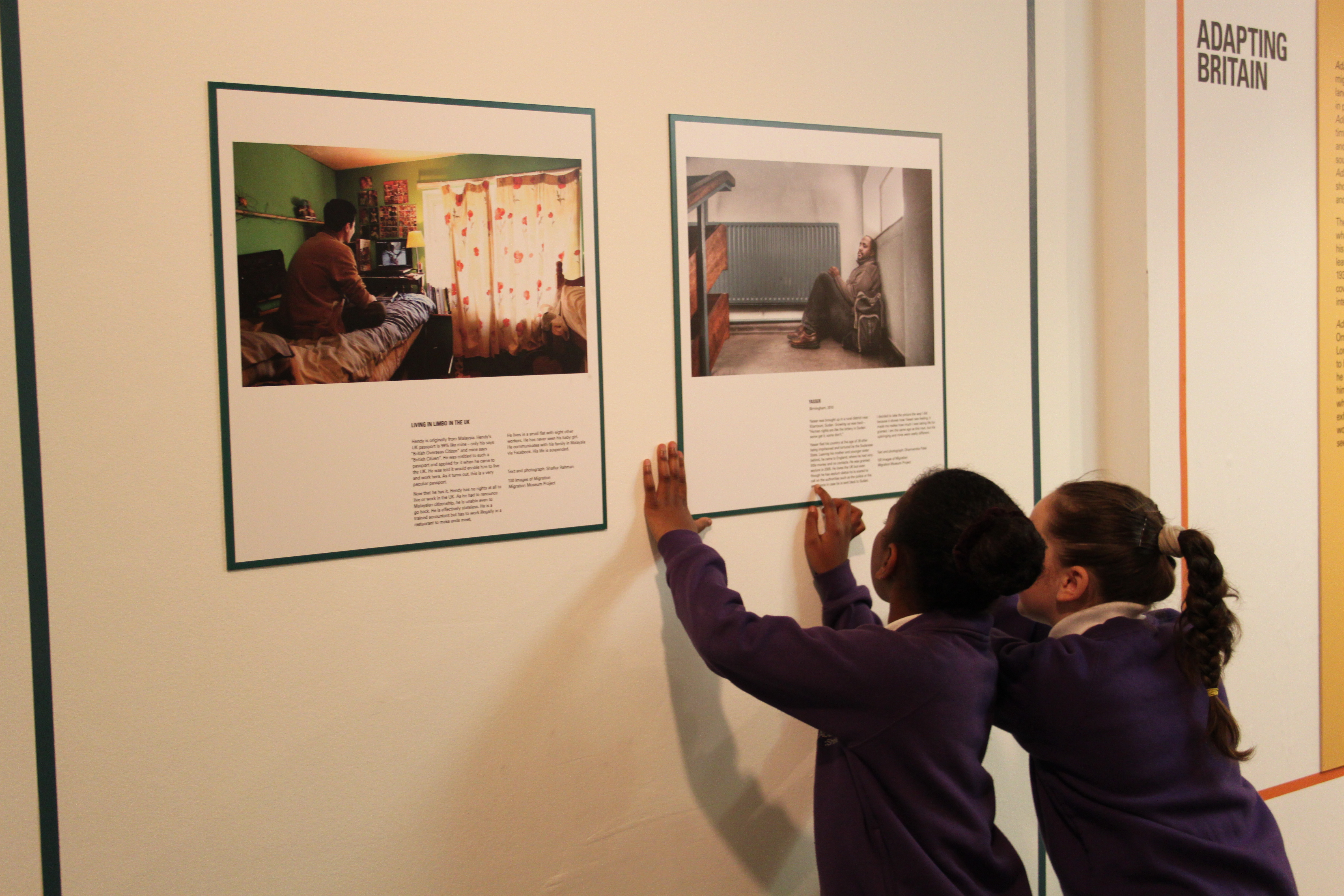

Two schoolchildren reading the caption for ‘Yasser’, a photograph by Dharmendra Patel which is part of the Migration Museum Project’s ‘100 Images of Migration’.

Although it was hardly his intention, in a way Powell played a part in my adopting this country. I came not as an economic migrant – indeed, today I would be financially much better off in the land of my birth – but because I wanted to be a writer; and this country provided me with that opportunity. Others have come for very different reasons and some, such as the ones flooding in now from Libya, because they have no other choice. But, whatever the reason, they have adopted and also changed this country, and this exhibition provides a glimpse of what has happened in the last 70 years. It can only be a glimpse – for this is a vast, complex, story – but, because it moves the focus away from the constant obsession with numbers onto showing us how people live, it is both immensely educative and very reassuring.

Mihir Bose is a distinguished friend of the Migration Museum Project and an award-winning journalist and author. Adopting Britain was at the Southbank Centre from April until September 2015.

12 August, 2015

The history of Boughton House – which this summer opens its doors to the public as part of the Huguenot Summer – offers a fascinating glimpse into the religious confusions of the 17th century, and an intriguing account of the employment of Huguenot craftsmen (and craftswomen), which cannot have been welcomed by the silversmiths and other workers of the time.

The North Front of Boughton House is directly influenced by Daniel Marot, one of the key Huguenot architects/designers (see below for more on Marot).

The north front of Boughton House, one of the most impressive stately homes in England, is modelled on the French Palais de Versailles (indeed, it’s known as the ‘English Versailles’), Louis XIV of France’s vast palace, the construction of which Ralph Montagu, the first Duke of Montagu, would have observed when an ambassador to the French court. On inheriting Boughton House on the death of his father, Montagu set about rebuilding and refurnishing it, enlisting the cream of Huguenot expertise to populate it with silverware, woodwork, painting, frames …

A detail of a screen by Mark Anthony Hauduroy after a design by Daniel Marot, 1720.

There are a couple of delicious ironies in that last paragraph.

Louis XIV, as one of our previous blogs recounted, was the monarch responsible for revoking the Edict of Nantes and for the subsequent departure of hundreds of thousands of French Protestants (the Huguenots) from France: a huge brain drain of which Britain was a principal beneficiary. And Ralph Montagu, while not a Huguenot, was a Protestant who had the ear of the (secretly) Catholic Charles II and his wife, Catherine.

But, whatever your religious persuasion, if you are looking for people to work on your big project, you want the best you can get, ideally without having to pay the world for it. Ralph Montagu inherited Boughton House in 1684 and threw himself with immense enthusiasm into the conversion of the property that his father had started. So how convenient that his inheritance of Boughton came the year before the revocation of the Edict of Nantes and the start of the arrival on our shores of so many skilled French craftsmen. Already immersed in French culture and style from his days as ambassador, Ralph set about commissioning, among others, Daniel Marot, the architect, furniture designer and engraver famous for his work at Hampton Court Palace; the artist Louis Chéron, who is responsible for the ceilings painted throughout the State Rooms; Peter Rieusset, the joiner who laid 271 yards of innovative parquet de Versailles at Boughton; the carver and gilder Jean Pelletier; the silversmiths Pierre Platel and Louis Mettayer; and Louis XIV’s favourite artist, Jacques Rousseau. Many of these people were employed to furnish the Duke’s house in Bloomsbury, London (Montagu House, the site of the now British Museum), but many of their works are on display this summer at Boughton, along with the first A–Z of London (by Huguenot Jean Rocque), miniature portraits by Isaac Oliver and some superb weaponry by Lewis Barbar.

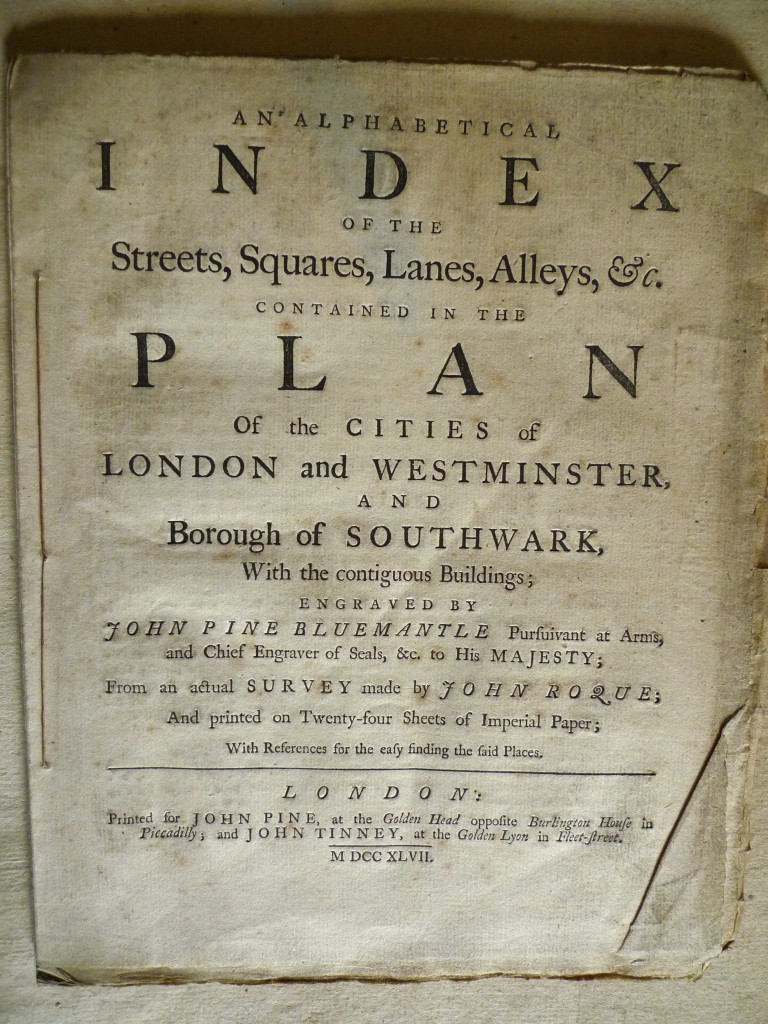

The title page of John Rocque’s Plan of London and Westminster. Rocque was the most sophisticated cartographer of the century and made an enormous contribution to the re-mapping of England (see below for more on John Rocque).

Silver sugar caster, the work of Paul de Lamerie (London, 1736). Paul de Lamerie qualified as a silversmith after the death of Ralph Montagu but is acknowledged as one of the great Huguenot craftsmen.

Details of the Huguenot exhibition at Boughton, which the Institut Français is supporting, can be found on the Boughton House website, where there is also an instructive interview with the exhibition’s curator, Paul Boucher. The Migration Museum Project has supplied two of the ‘contextualising’ panels to the exhibition, in an attempt to put the arrival of the Huguenots in the framework of migration to this country across the ages. The Independent has run a feature on the exhibition, which gives a detailed account of what there is to see.1

Nowadays people tend to speak in glowing terms about the influence of the Huguenots on British life and the extent to which they expanded the nation’s skill-set, increased its competitiveness, prepared the ground for the Industrial Revolution and generally wove their way (pun intended) into the fabric of the country. But in the clamour to celebrate the contribution of the Huguenots and their lasting legacy, it is worth sparing a thought for the people plying their trade in the 17th century – the silversmiths, weavers, goldsmiths and cabinet makers – who suddenly found themselves less in demand with the arrival of such skilled labour from Catholic France. Relatively little is known about the reaction of the indigenous workforce to the arrival of this European talent, but there are accounts of attempts to restrict the trading of Huguenot craftsmen. In 1711, for example, a petition was made to the Goldsmiths’ Company by ‘severall working goldsmiths, freemen of this Company’ complaining:

THAT partly by the generall decay of trade, and other ways by the intrusion of foreigners, severall of the workmen of the said Company have for the supports of their familys been put under the force of underworking each other, to the perfect beggary of the trade, and at length under the necessity of loading their worke with unnecessary quantitys of sother, to the wrong and pre-judice of the buyer, and the great discredit of the English workmen.

That by the admittance of the necessitous strangers, whose desperate fortunes obliged them to worke at miserable rates, the representing members have been forced to bestow much more time and labour in working up their plate than hath been the practice of former times, when prices of workmanship were much greater.

One outcome of these attempts to restrict trade may well be that a lot of Huguenot work was hidden, because the craftsmen, having no official entitlement to trade, sold their work to those who did – and these third parties then went on to pass the Huguenot work off as their own.

A pair of ‘over and under’ flintlock pistols by Lewis Barbar (active c1704–1741 – these are likely to be c1730), with turn-over barrels and safety catches. Each escutcheon is engraved with the Montagu crest (see below for more on Lewis Barbar).

It’s a shame that more isn’t known of the way in which Huguenot craftspeople in particular were received by the resident working population. In the absence of any clear information, the suggestion has to be that the two populations ended up accommodating themselves to each other in that ‘muddling along’ fashion that is often the British way. What seems to be clear is that, though there were riots against ‘the French’ in parts of England, there was generally less hostility shown to the Huguenot migrants than had (or has since) been shown to other groups. And the people who might understandably have been voicing complaints along the lines of ‘Those Huguenots … coming over here with their fancy ways and nicking our jobs’ would appear to have not been too damaged by their arrival in the longer term. It is abundantly clear that the country as a whole – on every conceivable level: economic, military, industrial, financial, cultural – benefitted dramatically from what has been dubbed ‘the quiet conquest’ of the Huguenots.

Further notes on Daniel Marot, John Rocque and Lewis Barbar

Daniel Marot had been working at the Gobelins tapestry workshops in Paris but fled France in 1684, arriving first in Holland, where he brought Louis XIVs’ court style to The Hague and Het Loo palaces. He arrived in England in 1694, a welcome addition to the network of Huguenot craftsmen. Highly influential in every area of design, he introduced to England the idea of the architect as interior designer, a notion followed later by William Kent and Robert Adam. Marot created significant designs for the royal palaces and gardens at Hampton Court and Kensington, and he created lavish interiors in the grand French manner for Montagu House. A significant amount of his Montagu panelling survives today at Boughton, where his influence can also be detected in the North façade. Marot’s designs heavily influenced furniture makers and were used by generations of the Pelletier family who worked extensively at Boughton and who played an important part in the development of rococo carving and frame making.

John Rocque: The Rocque family fled the Languedoc in Southern France and arrived in London in 1709 via Geneva, where John was born in 1705. John described himself as ‘dessinateur de jardins’, and his first publications in 1734 were meticulous plans of the royal gardens and parks at Richmond and Kew. He followed these with plans of Chiswick House, Hampton Court, Windsor Castle, Kensington Palace and Drumlanrig Castle, recording garden style before the advent of Capability Brown and the new natural landscape. Working in Huguenot Soho, he published his new map of London in 1746, attracting 246 subscribers, among them the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Montagu, to whom the overview page was dedicated. Its 24 sheets were extravagantly engraved in the latest French rococo style on large copper plates to the scale of 200 feet to the inch. The publication came with a separate A–Z street index (the first ever), which detailed 5,500 separate locations including squares, coal wharves, orchards, theatres, inns, distilleries, hospitals, prisons, asylums, schools and much more, including all 13 French churches. Rocque’s plans of English towns and their gardens remain some of the finest ever published and his pioneering UK road guides were used by many travellers. He died in London in 1762.

Lewis Barbar: Lewis (Louis) Barbar, a Huguenot from Poitou, came to London in 1688 and was naturalised in 1700. He became Gentleman Armourer to both George I and to George II. He died in 1741 and was succeeded by his son James. The best gunsmiths were Huguenots and they brought with them a hitherto unknown level of refinement, technical skill and workmanship, making London-French-made guns the best in the world. There was a huge market for pocket size pistols for personal protection and a large black market in French counterfeits grew up.

1 Boughton House is worth visiting in any case, of course. Much of the original structure and many of its 17th-century features have been preserved, largely as the result of the House ‘sleeping’ through two centuries, in the course of which there were no male heirs and it passed through the female line to families who had their main homes elsewhere (imagine having Boughton House as your second home!). An unintended benefit of this hereditary sexism is the unaltered state of many of the key features of the House.

Huge thanks to Paul Boucher, curator of the exhibition at Boughton House, for supplying images and captions for the photographs featured here, and also to Tessa Murdoch, deputy keeper at the Victoria & Albert Museum, for correcting errors in an earlier draft of this blog and for directing me to the petition about ‘necessitous strangers’.

26 March, 2019

This picture is part of a bigger project, developed in collaboration with Hackney Museum, about Cazenove Road, its community and its surroundings.

For me, Cazenove Road sums up the diversity of London: in this one road there is a mosque, a synagogue, a queer bar, a typical charity shop, second-hand shops, an art gallery, the organic shop, etc.