21 October, 2016

We went on a walk last Sunday, along with about 130 others.

It started in the cold, grey and wet, at a time when many of us would still be, if not in bed, certainly doing nothing much more energetic than turning the pages of a Sunday paper and slurping coffee. It ended in glorious early-evening light, with a rainbow over the Serpentine and, if not actual gold at the end of the rainbow, then the next best thing – cakes and prosecco.

Somewhere over the rainbow … Looking east from the Lido café in Hyde Park, the end-point of our Imprints walk. © Faiza Mahmood

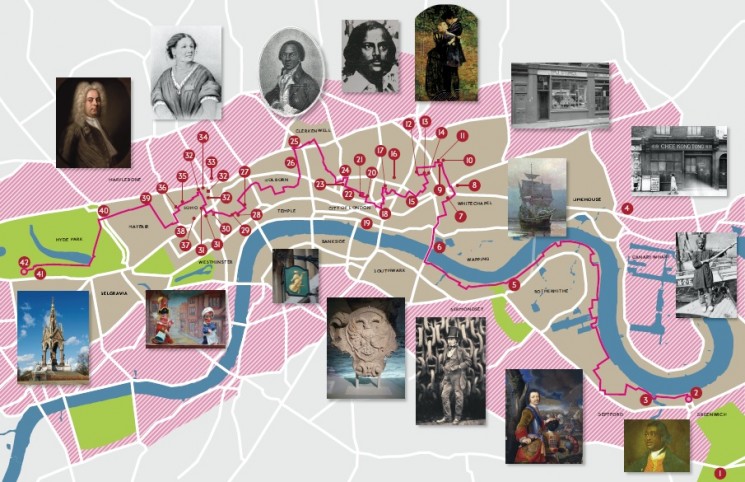

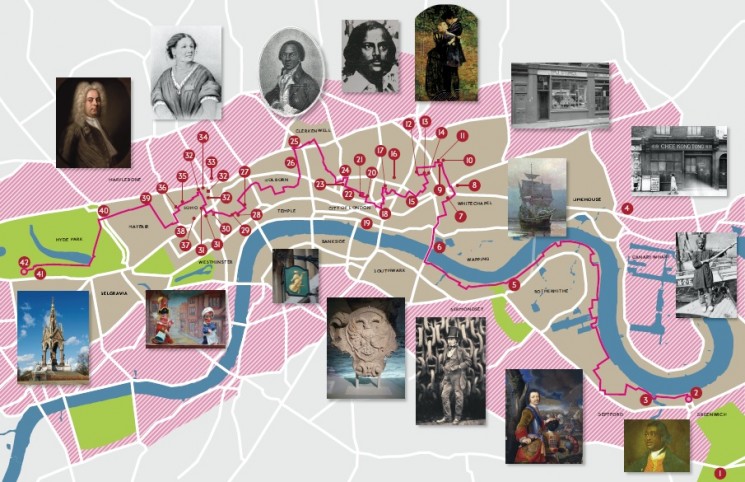

It started in Greenwich, where so many migrant stories have started in the past – George I prominently among them, borne to his disembarkation at the Old Royal Naval College aboard the ship Peregrine, but also, though much less regally, Ignatius Sancho, born on a slave ship and later a lobbyist for the abolition of the slave trade. It ended in Hyde Park, just short of the Albert Memorial, flamboyant statue to one of the most-loved migrants of the nineteenth century and the inspiration for the cluster of museums and institutions – Albertopolis – that now draw so many visitors to our capital.

The outline of the route the Imprints walk took through London. © Brandingbygarden

Not all migrants migrate from east to west of the city, of course, but it’s a useful hook to hang an event of this kind on. It’s certainly a long walk, that walk from arrival to establishment, and not all migrants make it with equal success, happiness and good fortune. And it was a long walk, literally, on Sunday, a full 15 miles and counting, which not all participants made with equal success, happiness and comfort of foot. But the overwhelming majority of those who started the walk completed it, and there was a sense of euphoric satisfaction in Hyde Park at the end of the day that may have had something to do with the prosecco on offer, or possibly with the sheer relief of the walk now being at an end – but which was mostly down to the sense of fulfilment and enjoyment of a day spent in good company, learning something about the myriad migration stories that make up the history of London, and of the multiple layers that make each street and region a palimpsest of the migratory experience: whether it’s the Brick Lane Jamme Masjid mosque, in a building that had previously been a synagogue and was, before that, a Huguenot chapel; or the building in Old Jewry, now housing the visa office for the People’s Republic of China but almost eight hundred years previously the site of the first synagogue in this country; or 25 Brook Street, home to George Frideric Handel in the 1700s and the more raucous stomping ground of Jimi Hendrix in the 1960s.

The Jamme Masjid mosque in Brick Lane – previously a synagogue and, before that, a Huguenot chapel. Spectacular minaret sadly not shown. © Aditi Anand

Divided into groups of 10 to 15, each led by an incredibly well-versed volunteer guide and supported by one of our magnificent volunteers, we walked along the south bank of the Thames to Tower Bridge, meandered through the East End, Brick Lane and Spitalfields, wandered through empty and storm-soaked streets in the City, rising again into Clerkenwell and Holborn – passing through the world of clockmakers, jewellers, lawyers and artists, before moving westwards through Covent Garden, Soho, Kensington and Mayfair. In Postman’s Park, Bill Bingham (our very own Ian McKellen) appeared out of nowhere, surprising us with a rendition of Shakespeare’s Thomas More speech (‘Grant them removed, and grant that this your noise / Hath chid down all the majesty of England … ’), delivered (in theory) in the early 1600s to quell riotous discontent at the arrival of the Huguenots. We stopped along the way to hear the story behind particular buildings, or about individuals who had lived in that area, or whole movements of people; and in-between we talked to each other about our own stories, about plans for the Migration Museum Project, about how our country would change in the wake of the recent referendum decisions.

Emily Miller, the MMP’s education manager, in Chinatown with Isabel Morrison. © David Wigram

We liked it so much we are already planning to do it again next year – at least once more in full length, and maybe on a number of other occasions, in a shorter form. And already we’re thinking, if this works so well in London, why wouldn’t it work just as well in any number of other cities: Newcastle, Manchester, Glasgow, Liverpool, Belfast, Bristol, Leicester? Get in touch with us if you want to help us plan how to extend it.

Oh, and we raised hugely important funds for the MMP’s work, too. Our target was to raise £20,000 to enable us to continue delivering exhibitions, events and education work in schools as we build the case for a permanent Migration Museum for Britain. At the time of writing, we are still a little short of our target – the equivalent of finding ourselves in Regent Street, when we need to be in Hyde Park. If you would like to help us reach our target or destination, please go to our MyDonate page.

And, just in case you can’t quite take our word for it, have a look at what some of the walkers had to say about the experience:

Epic day with informed guides – great fun despite the rain!

What a fab day! Like walking through a spread of London’s amazing history!

A wonderful way to explore London and discover how migration is a fundamental part of the city’s identity.

Amazing experience, informative and enlightening. Highly recommend it

I enjoyed seeing so much of London in one go, and learning about all the little histories and significances that would have gone unknown otherwise.

I loved the content and it’s great to have the map as a momento. Lots of highlights that I have been boring my nearest and dearest with: Mayflower pub selling US stamps – Rotherhithe tunnel used to have shops! – De Hems pub history … and of course the wonderful performance in Postman’s Park, a speech which I didn’t know and now love.

Very interesting, and I learned lots! Like the fact that it was easier to be black than Catholic in Tudor England! It made me think about things in a totally new way – I hadn’t thought of Paul Reuter as a German immigrant to London before!

We went on a walk last Sunday. It was a huge success, raising funds and fun in equal measure. Why don’t you come on the next one we organise?

The first Imprints: London Migration Walk took place on Sunday 16 October 2016. Huge thanks to our team of volunteer guides, all of whom were mines of information, wit and inspiration – and to the volunteers who supported them. Without you, this project would be struggling! But the biggest thank you goes to the 130 participants who so good-naturedly and energetically gave up their Sunday to support us on the walk, and did so without complaint, even when the skies emptied their load on us in the early afternoon. Thank you, thank you, thank you. Here’s to the next one!

6 October, 2016

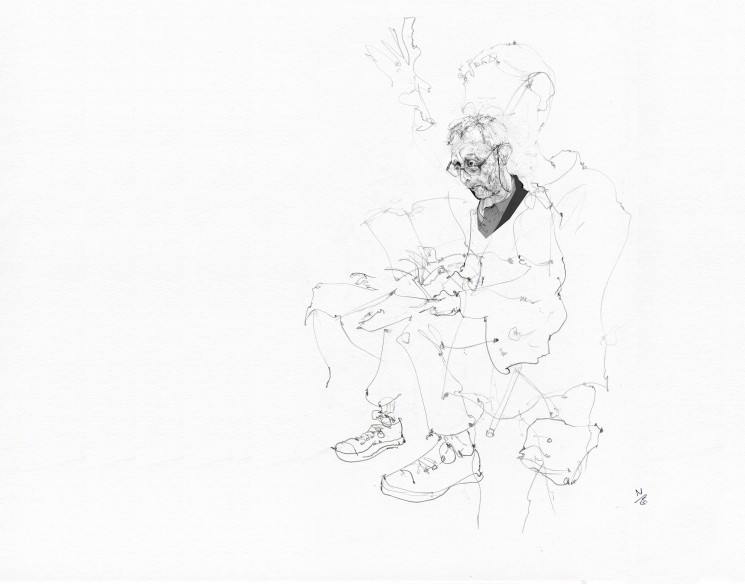

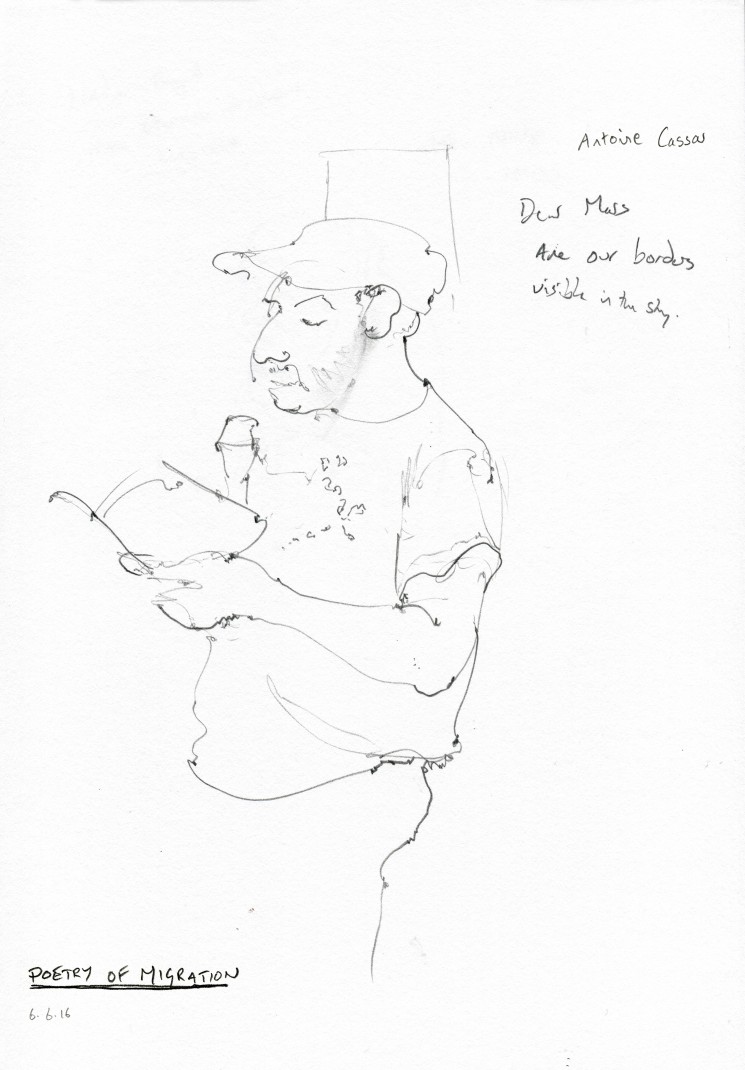

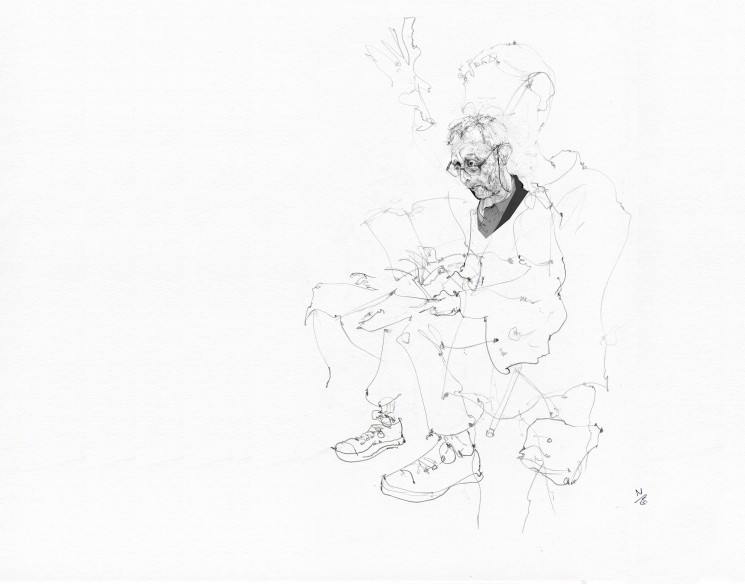

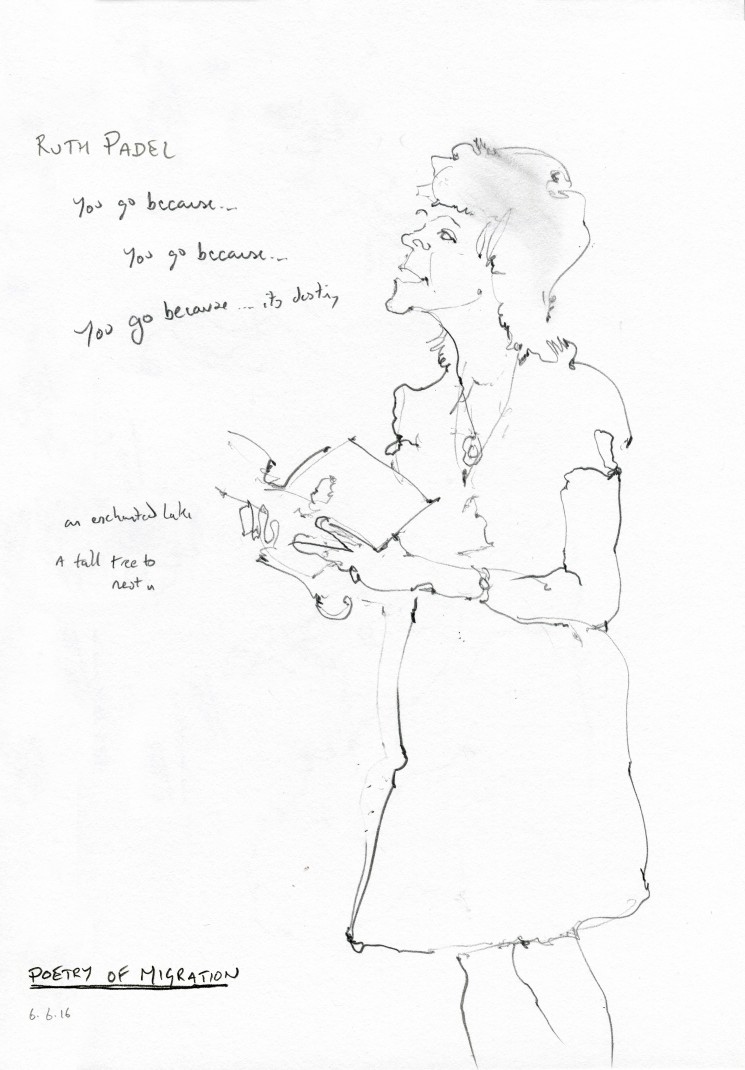

Michael Rosen, compering the ‘Poetry of Migration’ event at Londonewcastle Project Space earlier this year; drawing by Nick Ellwood.

One of the first events we held in the course of our three-week residency at Londonewcastle this summer (where more than 4,000 people visited our exhibition Call Me By My Name: Stories from Calais and Beyond) was the ‘Poetry of Migration’ on Tuesday 6 June. Michael Rosen (distinguished poet, writer, entertainer – and distinguished friend of the Migration Museum Project) compered the event, at which Ruth Padel and Jackie Kay were fellow guest speakers.

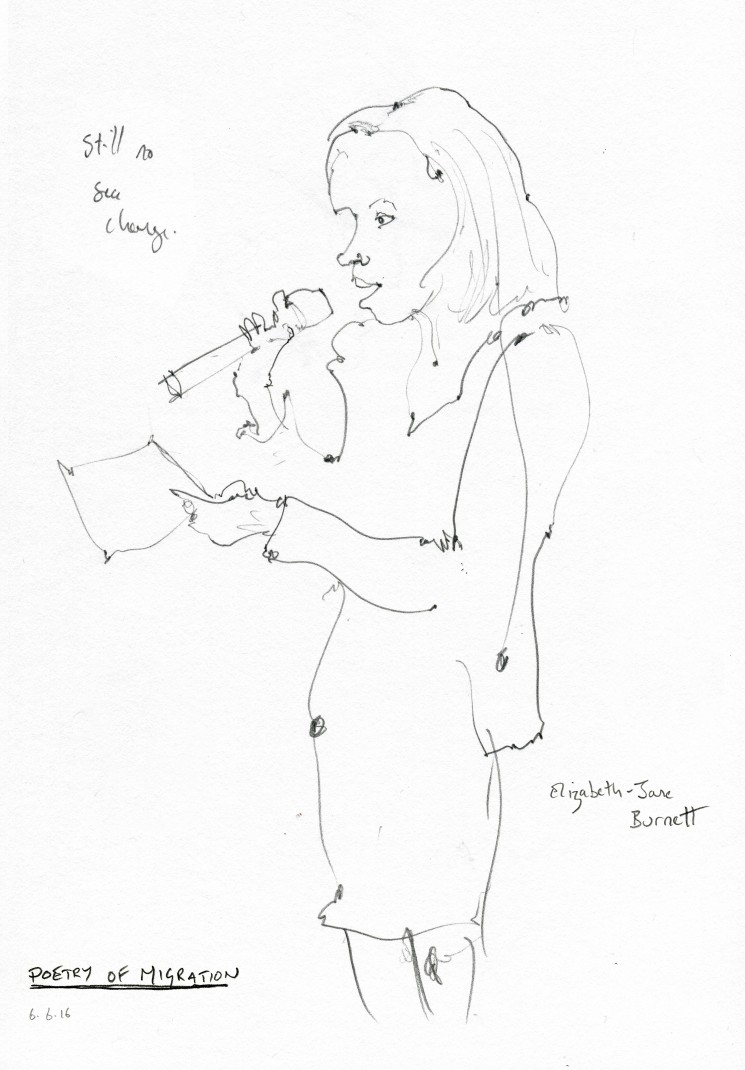

When we’d advertised the event, we had also asked people to let us know if they would like to present their own poems, so the evening was less about studious, respectful listening to the panel poets – though it was that, too – and more about participation. People presented their poems from the floor – Sophie Herxheimer, PJ Samuels, Antoine Cassar, Nadia Faydh and Elizabeth-Jane Burnett among them – and the audience expressed the full range of response you might have expected from an evening of poetry based around the theme of migration: tears, laughter, some anger, some despair. As a curtain-raiser for the exhibition itself, it was perfectly judged.

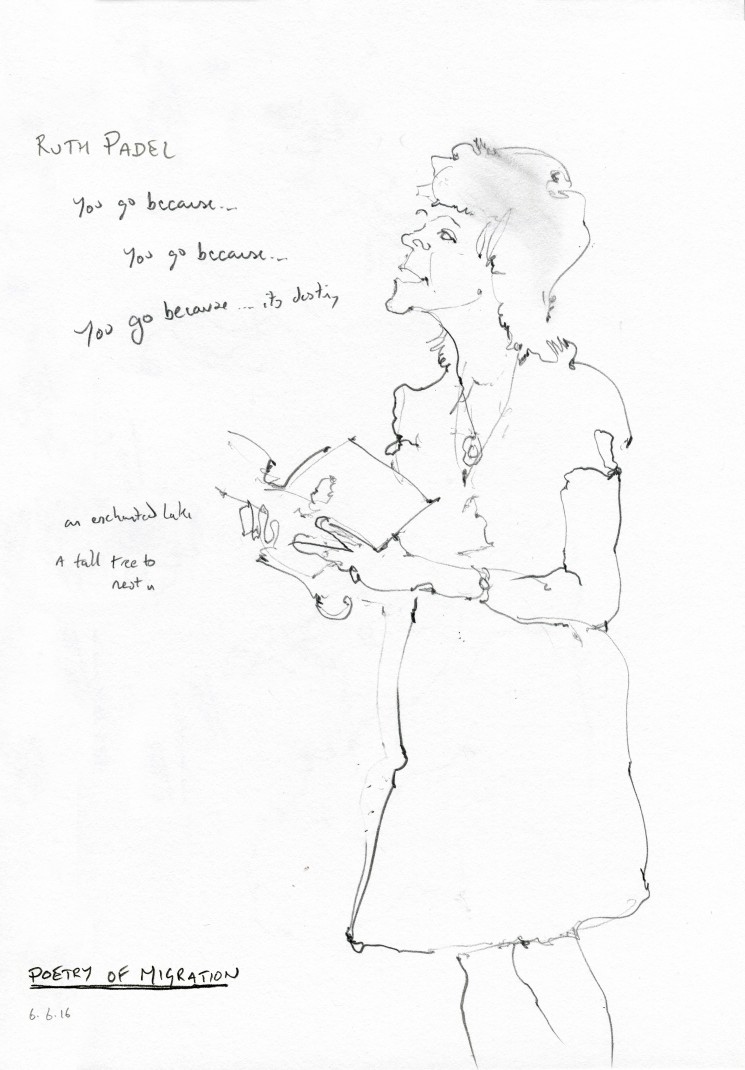

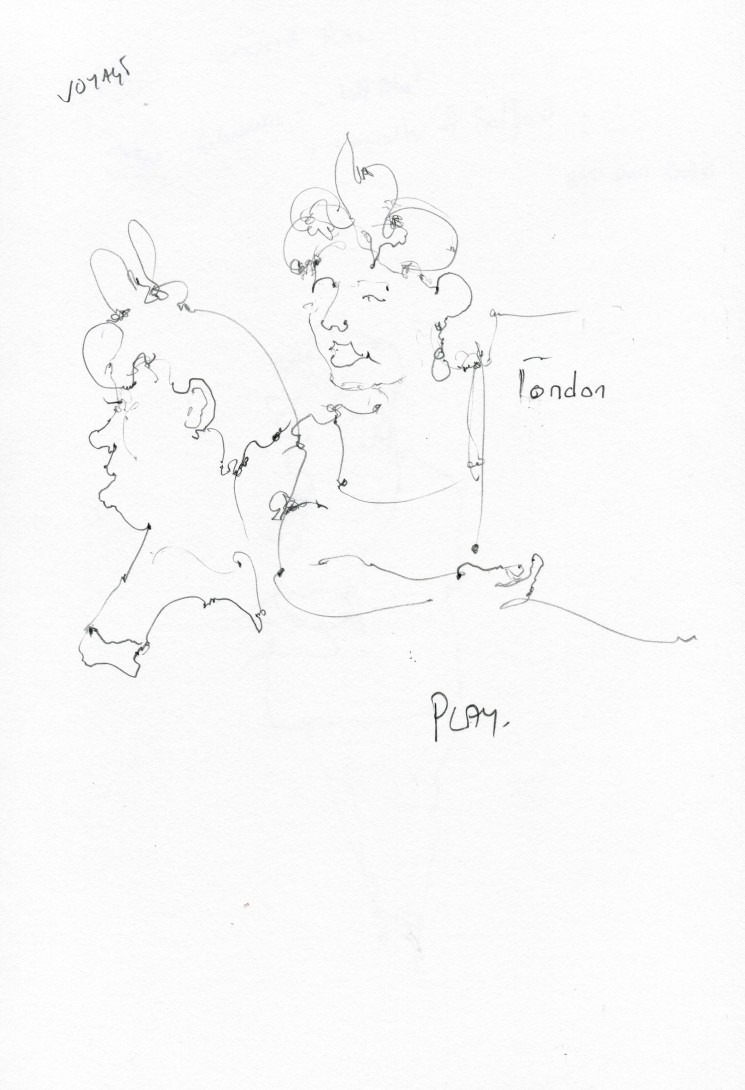

Nick Ellwood, the artist behind the panel drawings of Jungle residents in the middle room, sat in the audience and drew portraits of some of the performers. We’ve reproduced his drawings in this blog, together with some of the poems read out by the people he was drawing. It’s a rich combination: one of the artists we were privileged to work with for the exhibition producing beautiful sketch drawings of some of the incredibly talented writers we were thrilled to have perform at the event. We hope you enjoy this memento of the evening.

Ruth Padel

Purple Ink

She has waited three years for this. Too ashamed

to even half-tell the young woman in spectacles

tapping a purple biro on a desk

exactly what the soldiers did to her, each versatile

in his turn, she gets wrong Date your mother was born

and sees a stamp the colour of desert night descend on her file.

The Prayer Labyrinth

She went looking for her daughter. How many

visit Hades and live? Your only hope

is the long labyrinth of Visa Application

interviews with a volunteer from a charity

you’re not allowed to meet. You’ve been caught:

by a knock on the door at dawn

or hiding in a truck of toilet tissue

or just getting stuck in a turn-stile.

You’re on Dead Island: the Detention Centre.

The Russian refugees who leaped from the fifteenth floor

of a Glasgow tower block to the Red Road

Springburn – Serge, Tatiana and their son,

who when the Immigration officers

were at the door, tied themselves together

before they jumped – knew what was coming.

Anyway you’re here. Evidence of cigarette

burns all over your body has been dismissed

by the latest technology. You’re dragged

from your room, denied medication

or a voice. You can’t see your children,

they’re behind bars somewhere else.

You go on hunger strike. You’re locked

in a corridor for three days without water

then handcuffed through the biopsy

on your right breast. You’ve no choice

but to pray; and to walk the never-ending path

of meditation on not yet. Your nightmare

was home-grown; you’re seeking sanctuary.

They say you don’t belong. They give you

a broken finger, a punctured lung.

Ruth Padel, reading her poem ‘Time to Fly’; drawing by Nick Ellwood.

Time to Fly

You go because you heard a cuckoo call. You go because

you’ve met someone, you made a vow, there are no more

grasshoppers. You go because the cold is coming, spring

is coming, soldiers are coming: plague, flood, an ice age,

a new religion, a new idea. You go because the world rotates,

because the world is changing and you’ve lost the key.

You go because you have the kingdom of heaven in your heart.

And the kingdom of hell has taken over someone else’s heart.

You go because you have magnetite in your brain, thorax, tips

of your teeth. Because there’s food over the hill

and there’ll be gold, or more likely bauxite,

inside the hill. You go because your mother is dying

and only you can bring her the apples of the Hesperides.

You go because you need work.

You go because astrologers say so. Because the sea

is calling and your best friend bought a motorbike

in America last year. You go because the streets are paved

with gold and your father went when he was your age.

You go because you have seventeen children and the Lord will provide;

because your sixteen brothers have parcelled up the land

and there’s none left for you. You go because the waters are rising,

an ice sheet is melting, the rivers are dry

there are no more fish in the sea. You go because God

has given you a sign – you had a dream – the potatoes are blighted.

Because it is too hot, too cold, you are on a quest for knowledge

and knowledge is always beyond. You go because it’s destiny,

because Pharoah won’t let you light candles at sundown on Friday.

Because you’re looking for

an enchanted lake, the meaning of life, a tall tree to nest in.

You go because travel is holy, because your body

is wired to go, you’d have a quite different body and different brain

if you were the sort of bird that stayed. You go

because you can’t pay the rent: creditors lie in wait for your children

after school. You go because Pharoah has hogged the oil,

electricity and paraffin so all you have on your table

are candles, when you can get them.

You go because there’s nothing left to hope for;

because there’s everything to hope for and all life is risk.

You go because someone put the evil eye on you

and barometric pressure is dropping. You go because

you can’t cope with your gift – other people can’t cope with your gift –

you have no gift and the barbarians are after you.

You go because the barbarians are gone, Herod

has turned off the internet and mobile phones, the modem

is useless and the eagles are coming. You go because the eagles

have died off with the vultures and the ancestors are angry

there’s no one to clean the bones. You go in peace, you go in war.

Someone has offered you a job. You go because your dog

is going too. Because the Grand Vizier sent paramilitaries to your house last night

you have to go quick and leave the dog behind.

You go because you’ve eaten the dog and that’s it, there’s nothing else.

You go because you’ve given up and might as well. Because your love

is dead – because she laughed at you; because she’s coming with you,

it will be a big adventure and you’ll live happily ever after.

You go in hope, in faith, in haste, high spirits, deep sorrow, deep

snow, deep shit and without question.

You pause halfway to stoke up on Omega 3 and horseshoe crabs.

You go for phosphorus, myrtle-berries, salt. You go for oil

and pepper. It was your father’s dying wish.

You go from pole to pole, you go because you can,

you have no feet, you sleep and mate on the wing.

Because you need a place to shed your skin

in safety. You go with a thousand questions but you are growing up,

growing old, moving on. Say goodbye to the might-have-beens –

you can’t step into the same river twice.

You go because hope, need and escape

are names for the same god. You go because life

is sweet, life is cheap, life is flux

and you can’t take it with you. You go because you’re alive,

because you’re dying, maybe dead already. You go because you must.

© Ruth Padel from The Mara Crossing, Chatto and Windus, 2012

Sophie Herxheimer

London

Not zo mainy Dais zinz ve arrivink.

Zis grey iss like Bearlin, zis same grey Day

ve hef. Zis norzern Vezzer, oont ze demp Street.

A biet off Rain voant hurt, vill help ze Treez

on zis Hempstet Heese vee see in Fekt.

Vy shootd I mind zat?

I try viz ze Busses, Herr Kondooktor eskink

me … for vot? I don’t eckzectly remempber;

Fess plees? To him, my Penny I hent ofa –

He notdz viz a keint Smile – Fanks Luv!

He sez. Oh! I em his Luff – turns Hentell

on Machine, out kurls a Tikett.

Zis is ven I know zat here to settle iss OK. Zis

City vill be Home, verr eefen on ze Buss is Luff.

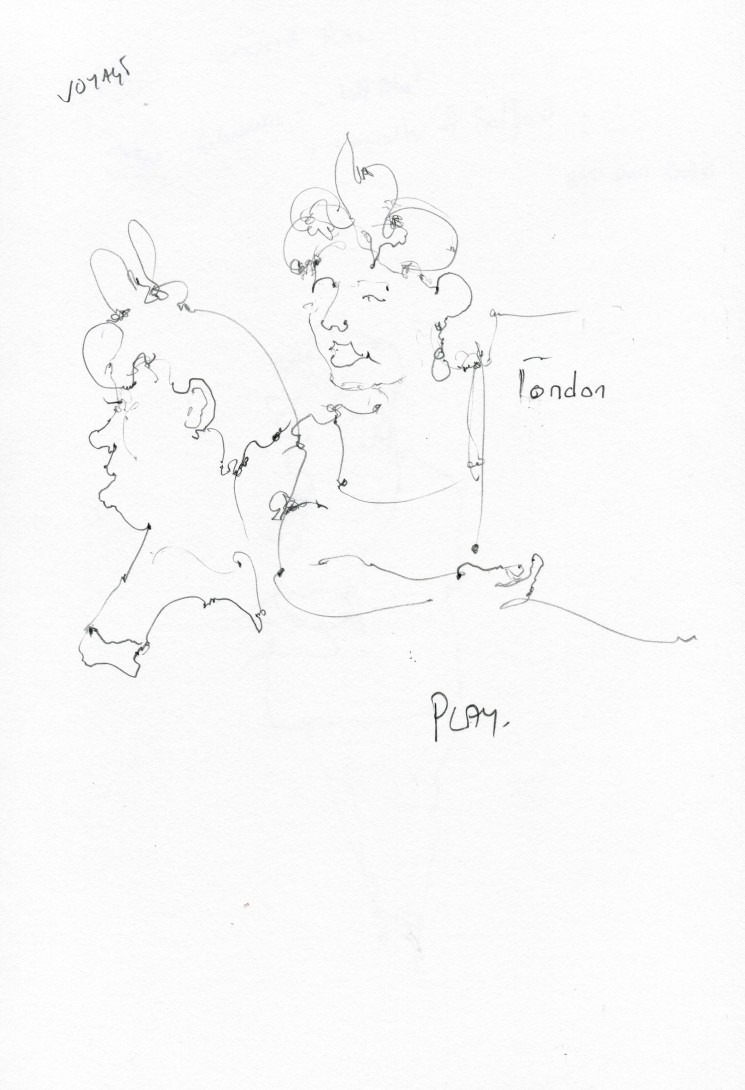

Sophie Herxheimer, drawn in full flow when reading ‘London’; drawing by Nick Ellwood.

Vosch by Hendt, Lern by Hart!

Ze yunkest off my grayt grayt

Grent-Childtrenn is lynink up

her Dollse oont Behrs for Klarse.

Ven zay slump in rekggitt

Exhorstschon, she arraintches zem

to lean on ze Kupboart. Zit up ztrate!

She Kommarnts. If Enny Vun

off you nose ze Aanser, don’t

schout out; poot up your Hendt!

Ze Svetter zat zis Teacher

vairs, looks ottley familiar.

Ze Vun Aunt Frieda sent from Vienna

for my Girl ven she voz small.

I see ze Vool still hess some Bountz.

Oont amazinkly, no Moss Holse!

Funny Frieda alvays sett she dittn’t

leik to knit: I heffnt ze Payschunz,

she leidt. Zis Svetter hess en intrikett

Pettern off blue Skvairs, raist in a Ridch

ofa nice veit Stokkink Stitch –

I marfellt et it zen, ven it arrifte, springink

like a Lemm from stiff brown Paper.

Vizzin Veeks of zat, Frieda, leik zo Menny,

voz seeztd, imprissont, murdtert.

Now zis endurink Laybor off hurze

iss vorn ess a Keint off Uniform:

kommarntink All who are born, or eefen

stufft: Make Sinks. Make Sinks up! Play!

© Sophie Herxheimer

‘London’ first appeared as no.22 in a series of concrete poetry broadsides from Brazil, called POW, subsequently appearing in Jewish Quarterly and Long Poem Magazine, and was also made into a film.

‘Vosch by Hendt, Learn by Hart’ has just been published in the Vanguard Anthology.

Nadia Faydh

Things I miss

When I wake up to the cloudy sky

Of London,

I feel overwhelmed:

A fit of yearning.

It is not that I want to go back,

but simply miss the way it was:

The sunny mornings,

The fresh smell of Cardamom

My mother used to make with tea

Or the smell of fresh bread,

When my father is back from the bakery …

Maybe I miss those Fridays,

When all the sisters gather around;

Voices of playing kids

Filling the air with delicious noise,

“the house can’t take us all,”

I would say,

My mother would stop me…

She likes it when we’re all there.

Maybe I miss dad’s big smile:

when his granddaughters

Greet him with a kiss.

I miss watching all the girls

Working in the kitchen,

Or Sit to the table laughing loud …

Dad would come in, take a picture,

To remember those moments I miss!

© Nadia Faydh

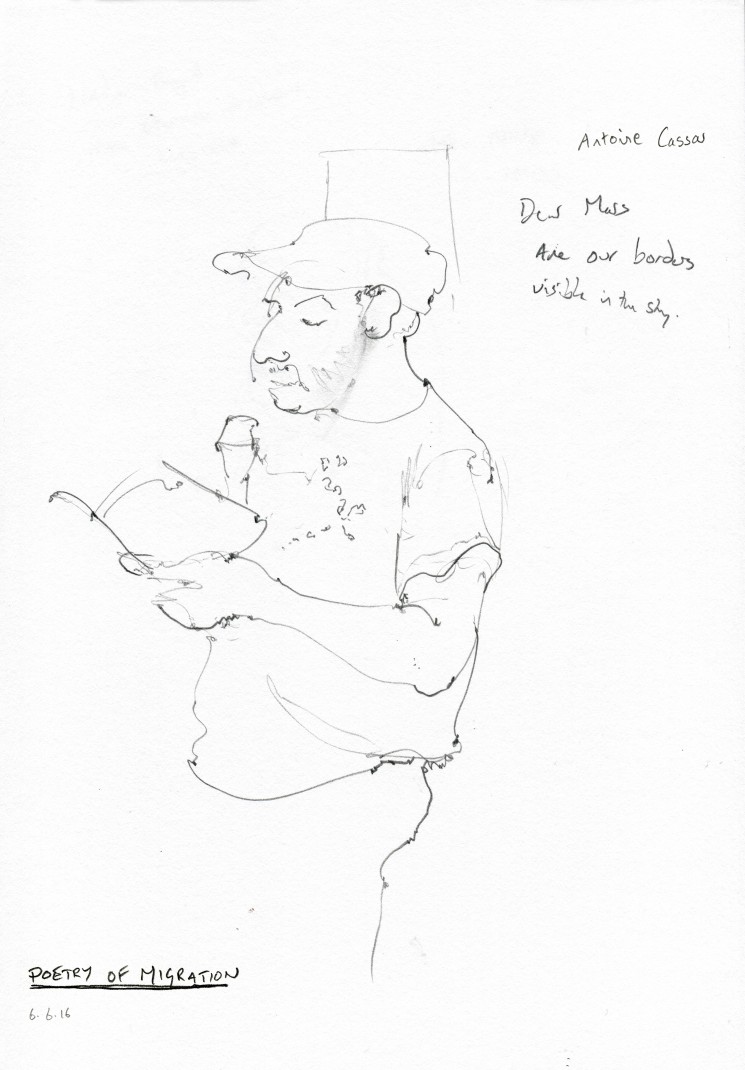

Guest readers at the event – Antoine Cassar on the left, Nadia Faydh on the right; drawing by Nick Ellwood.

Antoine Cassar

8 ħajki bla fruntieri

8 no-border haiku

1

L-ajruport. Tifel

ċkejken jaqbeż iċ-checkpoint.

Ma jafx b’fruntieri.

The airport. Boy leaps

over the customs checkpoint.

He knows no borders.

2

Tfajjel Sirjan

fuq il-kanvas tat-tinda

ipinġi d-djar.

A Syrian boy

paints houses on the canvas

of his tent.

Antoine Cassar, drawn by Nick Ellwood.

3

L-ebda bandiera

ma jistħoqqilha qima

daqs l-id li tħitha.

No flag, large or small,

deserves greater esteem than

the hand that sews it.

4

Il-bnedmin jaqsmu

l-fruntieri? Anzi. Il-fruntieri

jaqsmu ’l-bnedmin.

People cross borders.

It’s been that way ever since

borders crossed people.

5

Għeżież nies ta’ Mars:

jidhru l-fruntieri tagħna

fis-sema tagħkom?

Dear people of Mars:

are our borders visible

in your evening sky?

6

Ewropa! Intix

tisma’ l-imħabba ssejjaħ

minn qiegħ il-baħar?

Europe! Can you not

hear love calling out from the

bottom of the sea?

7

Għidli ftit, baħar,

kif għadek tmelles l-art

li tridek qabar?

Would you tell me, sea,

why you still caress the land

that has made you a grave?

8

Id-dinja tonda?

Saqsi lir-riħ, u ‘l-fens

mal-art ta’ Calais …

Is the world not round?

Ask the wind. Ask the Calais

fence, blown to the ground d…

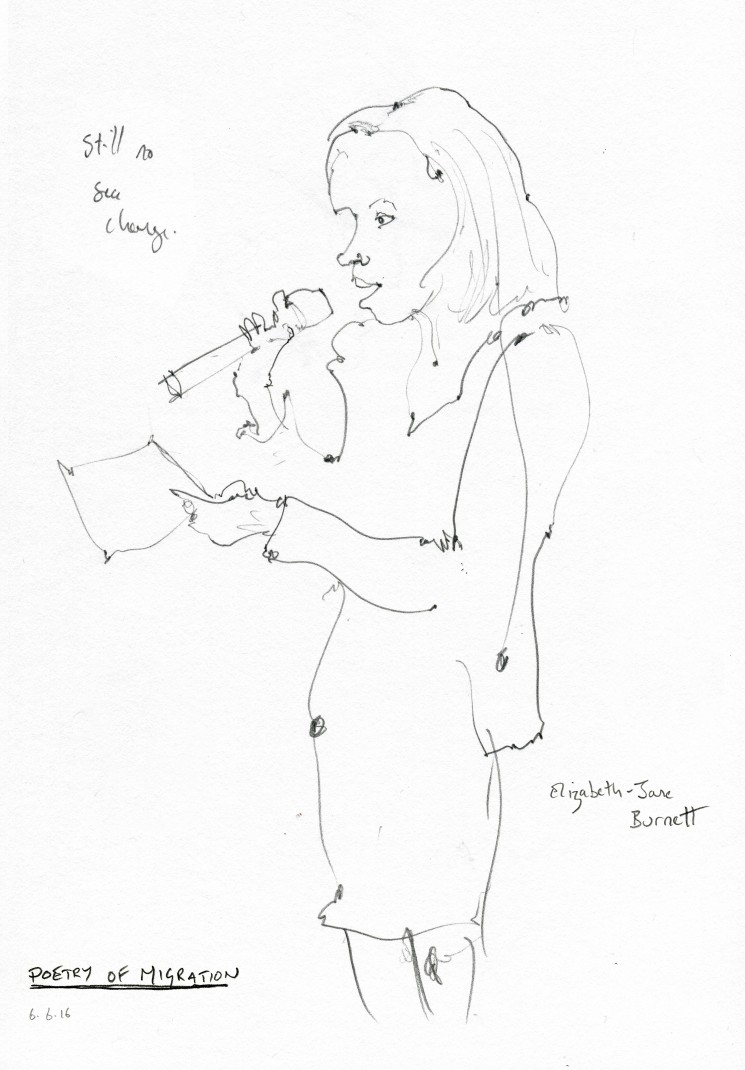

Elizabeth-Jane Burnett

Elizabeth-Jane Burnett, drawn by Nick Ellwood.

Talking to Ariel about Our Place in the Canon and Other Sea-Nymph Stuff

What did you notice, apart from the cold?

“It was –4 and three inches of snow.”1

What words will you choose to speak for you, whose

archive to bootleg to send over To:

recipients of black body unable to process except as appropriation or lost thing searching for warm amputations please

find history attached

in a speech of the eyes which do not lie or sound

as a Dali sequence of cuts let us process each other

through peel of vitreous fluid let us touch another fathom falls

as we see what we are made of: these yellow sands, these light bones

pulse as snowdrops through the dead days of autopsy:

still no sea-change.

1 Sam King, aged 81, a migrant from Priestmans River, Jamaica, to Bexley, Kent.

PJ Samuels

PJ Samuels, drawn by Nick Ellwood.

Whittle

I didn’t come here under a lorry

with bin liners over my head

so the carbon dioxide readers

cannot sense my breath

I didn’t sail here on a rubber dingy

and watch my brothers and sisters

become food for sea creatures

I didn’t cross a continent over land

needing to buy a new passport

and acquire a new name

at each border crossing

I am from Jamaica

Called the pearl of the Caribbean Sea

It is beautifully idyllic

My land is not torn apart by war

Just chained by terminal culture norms

I was on last rites

I bought a ticket, flew British Airways

Was served vodka and lemon en flight

Here I am

Tell me your story you said

Here is the altar, worship I brought me

And you made of me a sacrifice

Systematically stripped me

Peeled back my flesh

and pulverized my bones

Whittled me down to who I fuck

To how I fuck

To when I learned what fuck was

To how many times did you fuck her

what exactly did you do

Torn apart by need

whittled

Whittle

To cut small bits or pare shavings from

To reduce or eliminate gradually

To cut or shape wood with a knife.

Not a word much used

to describe a human being

But in your eyes, am I human?

You taught me inconsequential.

I brought the best of me

and had to learn that what you really wanted

was no part of me

With your callused carpenter’s hands

you whittled me down

to what you find consumable

there, you said,

I have made you beautiful

See how good I am to you?

here I am

your Pygmalion

your Aphrodite’s blessing

your social experiment

your triumph

Don’t I wear your guilty well?

Always with the dichotomy

of gratitude and grief

Wracked by survivors’ guilt

I sorrow for fragments of me left

in a land across waters

But it’s the pieces you took that remade me warrior

A constant itch under skin

I sit on the fence

vacillating between thank you and fuck you

And knowing even so

I am one of the lucky ones

Michael Rosen

Madame le Pen

Mme Le Pen,

la raison pourquoi

on a donné une étoile jaune

à l’oncle et à la tante de mon père

la raison pourquoi

on a demand qu’ils devaient attacher

une affiche disante ‘Enterprise juive’

à leur étal de marché

la raison pourquoi

ils ont fuit leur asile

dans la rue Mellaise à Niort

la raison pourquoi

ils se sont réfugiés à Nice

la raison pourquoi

on les a arrêtés et on les a transportés

à Paris, à Drancy, à Auschwitz et à leurs morts

est parce que

les officiers de Vichy

ont fait un ‘Fishier juif’ des juifs étrangers

et l’a donné aux Nazis au moment exacte

que la Résistance a dit bienvenu aux juifs

bienvenu aux étrangers

et c’est ça, la raison pourquoi

je vous dis ces choses

Mme Le Pen.

Michael Rosen, reciting his poem ‘To Madame le Pen�’; drawing by Nick Ellwood.

Mme Le Pen,

the reason why

they gave a yellow star

to my father’s uncle and aunt

the reason why

they told them they had to fix a sign

saying ‘Jewish Business’ on their market stall

the reason why

they fled from their refuge in the rue Mellaise

in Niort

the reason why

they took refuge in Nice

the reason why

they were arrested and transported

to Paris, to Drancy, to Auschwitz and to their death

is because the officials of Vichy

made a ‘Jewish File’ of foreign Jews

and gave it to the Nazis

at the exact moment

that the Resistance was welcoming

Jews and was welcoming foreigners

and that’s the reason why

I am telling you these things

Mme Le Pen.

Mother Father Cable Street

You Connie Ruby Isakofsky

From Globe Road in Bethnal Green

You Harold Rosen

From Nelson street, Whitechapel

You Connie with your mother and father

From Romania and Poland

You Harold with your family from Poland

You Connie

You Harold

your families working in the rag trade

Hats, caps, jackets and gowns

Hats, caps, jackets and gowns

You both saw Hitler on the Pathe News

You both saw Hitler Blaming the Jews

You both collected for Spain,

collecting for Spain

When Franco came

When round the tenements,

the whisper came

Mosley wants to march

Here, through the East End

So what should it be?

To Trafalgar Square to support Spain:

No pasaran?

Or to Gardiners Corner to support Whitechapel:

They shall not pass.

Round the tenements

The whisper came

Fight here in Whitechapel

The whisper came:

Winning here

We support

Spain there.

These are the streets where we live

These are the streets where we go to school

These are the streets where we work

They shall not pass.

You Connie

You Harold

Went to Gardiner’s Corner

You went to Cable Street

You piled chairs on the barricades

The mounted police charged you

A stranger took you indoors

To escape a beating

And thousands

Hundreds of thousands came here

Fighting Mosley

Supporting Spain

Thinking of Germany

And

Mosley did not pass.

You Connie

You Harold

Said, today the bombs on Guernica in Spain

Tomorrow the bombs on London here.

And you were bombed

the same planes, the same bombs

landing in the same streets

where you had said

they shall not pass

And the bodies

piled up across the world

Million after million after million after million

You Connie, your cousins in Poland

Taken to camps

Wiped out

You Harold, your uncles and aunts in France and Poland

Taken to camps

Wiped out.

But you Connie, my mother

You Harold, my father

You survived

You lived

We were born

We grew

You mother

You father

told us these things

I write these things

And today,

I tell you these things

We remember here together

Thanks to you

And we say:

They shall not pass.

© Michael Rosen

3 August, 2016

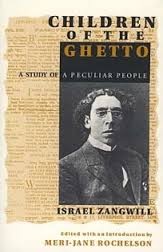

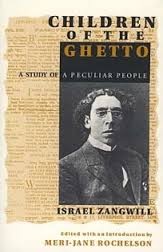

What was the attitude of the Victorians to immigration, particularly Jewish immigration? What was the mood of the country leading up to the passing of the Aliens Act in 1905? And what parallels are there between the experience of immigrants then and now, one hundred years later? The focus of this guest blog is Israel Zangwill and his late-19th-century book Children of the Ghetto; Nadia Valman, who has created an app that allows people to explore the Spitalfields area through the medium of the book, flags up a surprising number of parallels between the two periods.

Children of the ghetto

Israel Zangwill’s 1892 novel Children of the Ghetto is a landmark publication in English literature: the first Victorian novel to offer an insider’s perspective on immigrant lives in London. It offered the reader a wide social panorama, including rabbis, schoolteachers and philanthropists, garment workshop bosses and machinists, socialist organisers and poets, immigrant parents and English-born children. Published to great acclaim at a time of rising popular feeling against immigration, the novel aimed to make a significant political intervention by fostering understanding of a mostly voiceless migrant population.

Zangwill was in a unique position as a writer. He had lived most of his childhood in Spitalfields, the area of east London where tens of thousands of Jews, fleeing pogroms, expulsions and economic restrictions in the Russian empire, had settled during the 1880s and 90s. As a teacher at the Jews’ Free School there, he worked among the children of immigrants, most of whom entered school speaking no English. But as a graduate of London University who had moved to Bloomsbury and renounced religious practice, he also observed the Spitalfields Jews at a distance. His novel documented the close ties felt among people who, he wrote, had been forced to live in isolation for centuries, and could not easily shrug off the weight of that history.

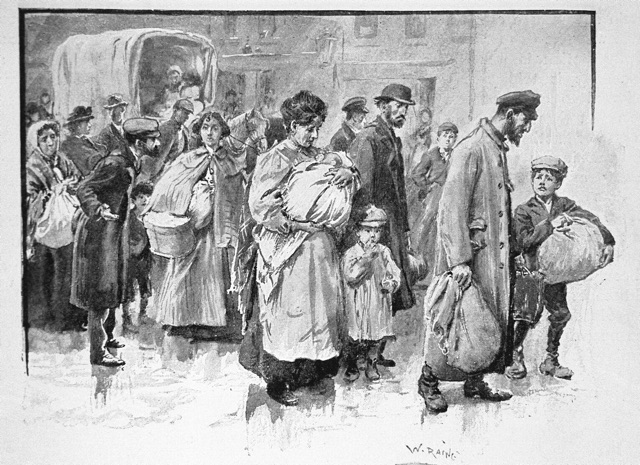

Children of the Ghetto blasted onto the literary scene in the year of a general election in which immigration was a hot political topic. Back in the early 1880s, there had been widespread sympathy for the plight of Jews escaping persecution and destitution, and large protest meetings in cities all over the country condemned the Russian pogroms. Soon, however, attention turned to the social impact of immigration. Spitalfields, often referred to as the ‘Jewish colony’, attracted the fascinated gaze of sociologists and journalists. ‘My first impression on going among them,’ wrote Mrs Brewer in the Sunday Magazine in 1892, ‘was that I must be in some far-off country whose people and language I knew not. The names over the shops were foreign, the wares were advertised in an unknown tongue, of which I did not even know the letters, the people in the streets were not of our type, and when I addressed them in English the majority of them shook their heads.’ Others reacted with antagonism rather than bewilderment. The anti-immigration campaigner Arnold White declared that, unlike Christian refugees to England, Jews formed ‘a community proudly separate, racially distinct, and existing preferentially aloof … A danger menacing to national life has begun in our midst,’ he warned, ‘and must be abated if sinister consequences are to be avoided.’

As with other immigrants before and since, the Jewish immigrants of the 19th century introduced new tastes and refinements to London.

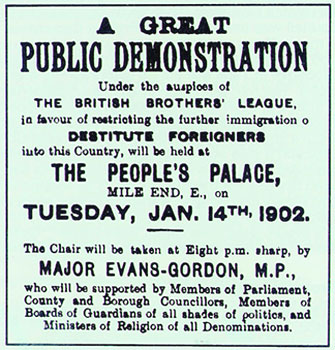

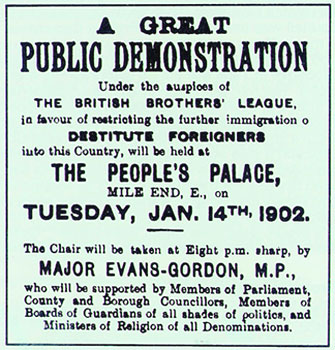

By the early 1890s a group of Conservative back-benchers were increasing pressure on the government to control immigration. The failure of their efforts in the following years has been attributed by some to the impact of Children of the Ghetto. But rising unemployment and discontent at the end of the decade provided the opportunity for two East End Conservative MPs to form the British Brothers League, which aimed to galvanise local support. A mass rally in January 1902, held at the People’s Palace, Mile End Road, was advertised as a ‘great public demonstration in favour of restricting the further immigration of destitute foreigners into this country’.

The British Brothers’ League was formed in 1902 to campaign against immigration; it was organised on vaguely paramilitary lines. Dribbling into obscurity in 1923, the League was in many respects the precursor of the British Union of Fascists, which had a significant and unsavoury presence in the 1930s.

It was partly in response to this popular hostility that the first immigration restriction act for a century was passed in Britain – the Aliens Act of 1905. The Act, while retaining the right to asylum on political or religious grounds, gave government inspectors power to ‘prevent the landing of undesirable immigrants’, including ‘invalids’ and ‘paupers’ – those who could not show that they were capable of supporting themselves – and thus excluded not only the sick and elderly but also those who arrived destitute, often having been conned or robbed of their assets on the journey.

There are many resonances between popular anti-immigrant feeling then and now. In the early 20th century, it helped to channel and defuse Eastenders’ anger at their chronic poverty and insecurity. Jews were accused of lowering the standard of living with ‘sweatshops’ – small workshops characterised by poor working conditions, long hours, low pay and seasonal fluctuation, and of causing the housing shortage that had led to extreme over-crowding. Yet in fact both problems were rife in the East End long before the Jews’ arrival. Hostility to immigrants came from pervasive lack of understanding about the real economic causes of local unemployment, such as trade depressions, mechanisation, and competition from manufacturers in the provinces.

In this context, there was considerable pressure on Israel Zangwill to produce an uplifting account of Jewish Spitalfields, countering misconceptions and demonstrating how Jewish immigrants were contributing positively to the economy and living pious, law-abiding lives. That pressure is evident in aspects of the immigrant subculture that he deliberately left out of the novel: the gang violence, the prostitution, and gambling clubs.

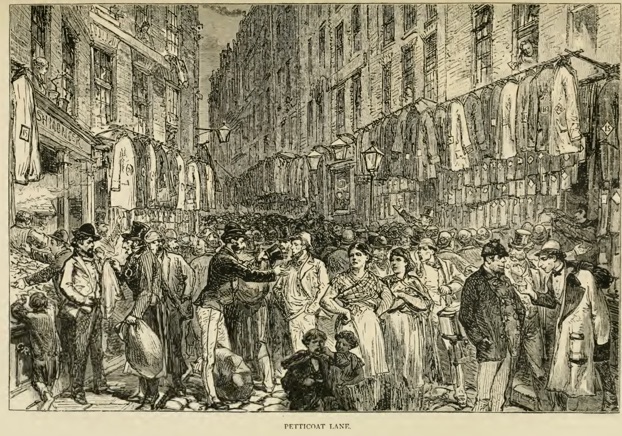

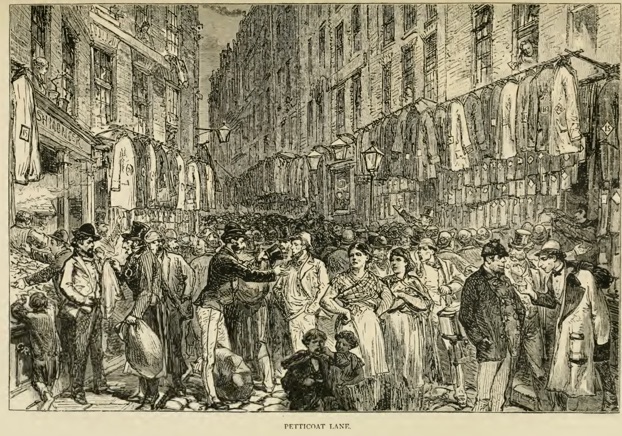

Nonetheless, Zangwill took a bold stand against a number of contemporary stereotypes. Petticoat Lane market, for example, at the heart of the immigrant area, was invariably associated in the Victorian press with danger and dodgy dealing, but it has a very different meaning from Zangwill’s perspective. He describes Petticoat Lane as a place where Jews of all social classes congregate to experience the smells and tastes that remind them of their roots.

Petticoat Lane, 1878.

‘The Lane was always the great market-place,’ he writes, ‘and every insalubrious street and alley abutting on it was covered with the overflowings of its commerce and its mud … The famous Sunday Fair was an event of metropolitan importance, and thither came buyers of every sect … A babel of sound, audible for several streets around, denoted Market Day in Petticoat Lane, and the pavements were blocked by serried crowds going both ways at once.’ In his account of the market, Zangwill emphasises its vitality and vulgarity. The distinctive dynamism of immigrant culture, for him, was precisely what was valuable about it. But the market was far from being a ‘ghetto’: it was here that Jewish culture was shared with ‘buyers of every sect’. Unusually for a Victorian novelist, he regarded London’s multiculturalism as an asset to be prized.

Petticoat Lane, 2015.

Zangwill also broke new ground in depicting the diversity of contemporary Jewish life. Although it would have been easier to advocate for Jewish immigrants by representing them as a cohesive community with shared needs and aspirations, he instead drew the novel’s dramatic scenes from the conflicts of class, religion and generation that fissured it. He intended, he wrote, ‘to exhibit clearly that the Jew, like the Englishman, cannot be summed up in any single, or indeed in any score, of types’. Children of the Ghetto explores divisions among Jews who are wealthy and poor, orthodox and secular, immigrant and English-born, men and women, parents and children. This was a fractured, deracinated population – uncertain of its future, at a moment of critical change.

It’s this complexity that I want to convey in Zangwill’s Spitalfields, a smartphone app that uses Children of the Ghetto as the basis for a walking tour of the Spitalfields area. The app brings to life the dilemmas that beset immigrants and their children in the context of fierce debates about migration from more than a century ago. Like the novel, the app’s narrative follows the story of Esther, a London-born ‘grandchild of the ghetto’, her routes between soup kitchen and school, attic home and marketplace and her changing relationship to Spitalfields. Many of the sites where Zangwill stages the novel’s key scenes are still extant, offering a series of physical settings where the app augments extracts from the novel with related visual and aural materials from the period. And I’m able to use the unique capacity of mobile digital technology to immerse the listener in Spitalfields’ past while remaining attentive, or becoming more attentive, to its present, as you walk through a streetscape shaped by more recent histories of migration.

Perhaps the most remarkable fact about Children of the Ghetto is that it became a bestseller following its publication and was repeatedly reprinted for several decades. Written in the context of widespread confusion about immigration, the novel opened up a little-known world to the reading public. But Victorian readers found more than novelty in its pages: they also encountered the story of a daughter rebelling against her father’s authority, a father striving to understand his son’s lack of interest in his family’s traditions, a woman longing for the warmth and security of her childhood home. Readers discovered that the struggles of Jewish immigrants in Victorian London were not so different from their own.

Nadia Valman is Reader in English Literature at Queen Mary, University of London. She researches and teaches the literature of east London, where she also leads guided walks. She wrote and curated the free downloadable smartphone app Zangwill’s Spitalfields.

11 July, 2016

One of our core ambitions has always been to tell the long story of migration into and out of this country – partly because every immigrant into one country is an emigrant from another, and partly because people forget that, until the 1970s, the United Kingdom was a net exporter of people: more people left the country than entered it. The story of emigration from this country is fascinating and often horrific – and the parallels between ‘then’ and now are all too obvious. In this guest blog, Matthew Crampton, writer and folk singer (whose latest book is Human Cargo: Stories and Songs of Emigration, Slavery and Transportation), tells some of these stories and shows how folk song can allow the voice of people caught up in this practice to be heard.

Behind every statistic, a human story

Every statistic I read on migration suggests it brings economic benefits to a host country. Yet most newspaper headlines damn migrants. How do we bridge this disconnect? It’s not enough to state facts. People love their myths. Moreover, those on both sides of the argument tend to view migrants solely as statistics. Maybe story, and song, can help us re-frame the discussion.

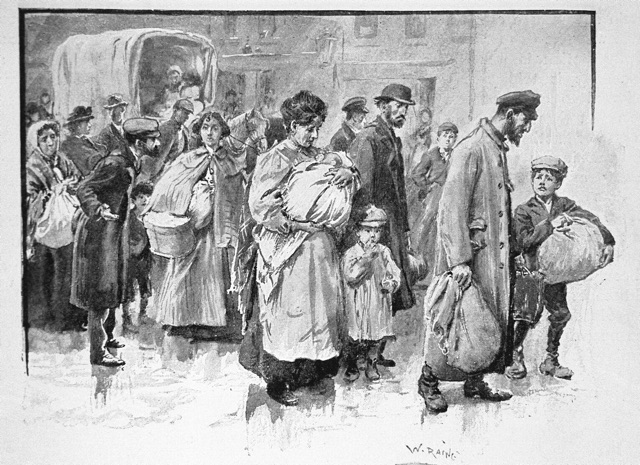

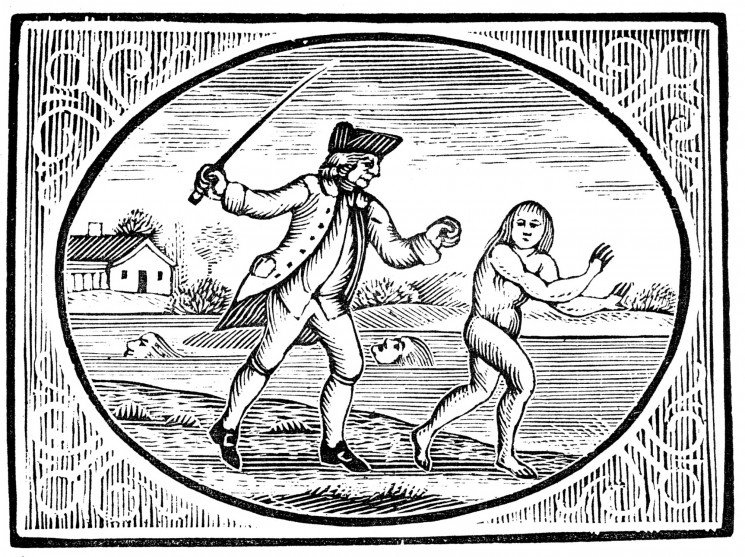

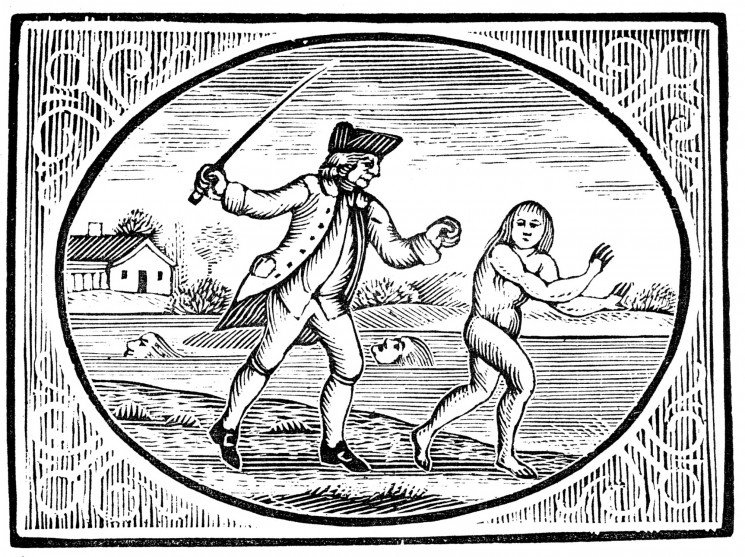

A quayside departure – the young man has just been ‘pressed’ into joining a ship headed for the colonies.

If you look at the lives of those trafficked* or transported in past centuries – particularly in the 1700s and 1800s – you see clear parallels with today. Patterns of cruelty do not change. In 1800, for example, frightened families filled the dockside of the Scottish town of Fort William. They were escaping famine, disease and landlords. Like Syrian families today, they were prey to the slick promises of unscrupulous traffickers, such as agent George Dunoon. He promised comfortable passage to America. Yet he crammed the desperate emigrants into rotten hulks. The crossing was horrific. The death rates for emigrants – though paying passengers – were sometimes higher than on slave boats. How could this be?

The answer, depressingly, is an economic one. Slavers were paid for the cargo they delivered alive; however cruelly the slaves who constituted this cargo might be treated, they were of value to slavers only if they survived the crossing. Emigrant captains, by contrast, were paid in advance, so they had less incentive to keep their cargo breathing. Indeed, the more that died, the more space, and food, for those left behind. Of course there was no moral equivalence: most emigrants, however desperate their circumstances, travelled voluntarily; slaves were transported against their will. And emigrants who survived, and arrived, were often free citizens, not slaves – whereas there was no such freedom for any slave who survived the journey.

Sex slavery was a common feature of the 18th and 19th century slave trade, occasionally, as here, featuring white women.

The 18th and 19th centuries saw millions of people on the move, a greater proportion of the then populations than today (though Syria is re-balancing the equation). And many of those people were Europeans. It’s estimated that nearly one third of the German-speaking adult population of Europe – some 15 million in total – migrated during the 1700s.

Tiny Britain had seized huge colonies, and needed labour to exploit this new land. Slaves were to provide much of this labour, particularly after the slave trade became highly sophisticated in the latter half of the 18th century. Before that, Britain also exported political prisoners to work the colonies, with Oliver Cromwell sending thousands of Scottish and Irish prisoners to the Carolinas (on the east coast of America). Later, the British government sent felons: you could be transported for 14 years for as small an offence as stealing a loaf of bread. This provided significant labour, at first to America, and then, after US independence, to Australia.

In any case, the majority of Europeans arriving in colonial America were indentured servants. Such servants entered a contract to work for another person for a defined period of time, usually without pay but in exchange for free passage to the new country; they could be bought or sold and, on average, they did not survive their period of indenture. But many did survive, like the remarkable Peter Williamson. He was kidnapped aged ten in Scotland, then ‘spirited away’ to be sold as a servant in South Carolina.

While playing on Aberdeen quay, he later wrote, ‘I was taken notice of by two fellows belonging to a vessel in the harbour, employed by some worthy men of the town, in that villainous and execrable practice called kidnapping.’ Such traffickers, known as ‘spirits’ (hence ‘spirited away’), sold him in Philadelphia – for sixteen pounds – for seven years’ indenture on a plantation. Much of that money would have made its way back to the Aberdeen magistrate who helped organise the seizure.

There are many such stories of human cargo from the time.

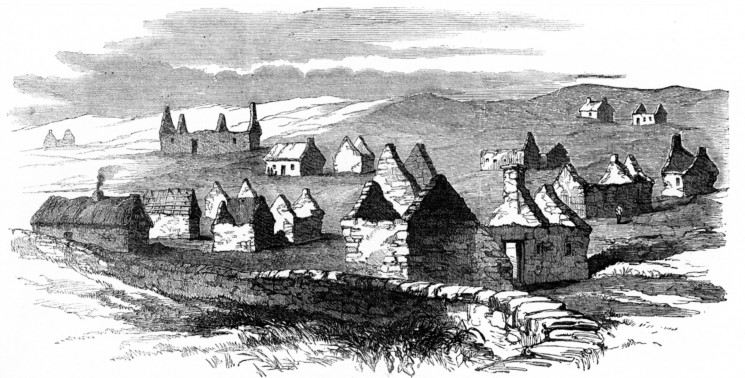

The Highland Clearances, undertaken in the 18th and 19th centuries by unscrupulous landowners seeking to change the use of the land from agriculture to sheep farming, was the source of a huge movement of people from the heart of Scotland to the large towns and, further afield, to the British colonies. In its wake, abandoned crofts were the only record of a once-thriving Gaelic community.

Catherine McPhee was ‘cleared’† by her Hebridean landlord, who gave her just hours to pack up her life before forcing her onto a boat, next stop Nova Scotia. James M’Lean was an American sailor, pressed into the Royal Navy and forced into many years of horrific service across the world. Robert Whyte wrote a chilling account of life (and death) aboard an Irish ‘coffin ship’ bearing emigrants to America, which was later published as Robert Whyte’s 1847 Famine Ship Diary: The Journey of an Irish Coffin Ship.

And Olaudah Equiano provided us (in his 1789 autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano) with a rare first-hand slave’s account of the Middle Passage from Africa to America. He wrote ‘It was said the stench of a slave ship was so strong that other sailors could smell it a mile downwind, and that the odour of vomit, sweat and faeces of its human cargo worked its way into the very wood and could not be scrubbed away.’

Olaudah Equiano was instrumental in drawing to public attention the horrific 1781 massacre of African slaves on the slave ship ‘Zong’. The ship’s crew threw 133 Africans over board when the ship ran low on drinkable water – but also to cash in on insurance repayments for the ‘loss’ of the ship’s cargo. The case against the ship owners was unsuccessful but is said to have led to the abolitionist movement in Britain.

These stories help humanise the history of migration. But history tends to record the rich, the resourceful and the lucky. What of the masses, the poor or illiterate, who left no testimony?

Here, interestingly, we can turn to folk song. Vast numbers of folk songs exist from this period. They’re mostly anonymous, passed down orally until transcribed by a song collector. Or they were printed crudely on broadsheets, sold cheaply in the streets of Hanoverian or Victorian England.

Though anonymous, folk songs can provide an authentic record of ordinary people. There’s a song called “Paddy’s Lamentation”, or “By the Hush”, whose chorus sings:

Oh you boys, now take my advice

To America I’d have you not be coming

For there’s nothing here but war,

And the thundering cannons roar,

And I wish I was back home in dear old Ireland.

Union flag and cannon – on their arrival in America, many indentured servants found themselves drafted in to fight on behalf of the Unionist cause.

“Paddy’s Lamentation” highlights a little-known story about migration from the time. During the American Civil War, the Union Army sent recruiting agents to post-famine Ireland. They promised free Atlantic passage to young men, in return for a bit of work. On arrival in New York, all excited, the men would not be allowed to disembark until they’d signed up to join the army of the northern states. Within months, or weeks, they might be on the battlefield of Gettysburg, where, like the narrator of this song, they lost a leg, or worse.

Migrants who’d survived the crossing could not depend on Trip Advisor to chronicle their duplicitous traffickers. But word could reach back home with songs like this.

For my book Human Cargo, I found many such stories, and songs, which chart the breadth of migration in past centuries. These touch areas such as emigration, slavery, the press gang, sex trafficking and convict transportation. Where possible, I’ve included modern testimony, for example contrasting a trafficked Japanese sex worker from 1905 with the recent experience of a young Albanian woman lured into Italy. Or I link the vicious practices of the press gang with the recruitment of African child soldiers today.

As I say in the introduction, today’s refugee crisis demands witness – and action – but is hard to grasp. Story and song won’t solve the problems, but they can help find a way in.

*The terms ‘trafficking’ and ‘transportation’ in the 18th and 19th centuries include those carried involuntarily – such as slaves, prisoners and the forcibly displaced – and those travelling by choice (even if it was a desperate choice), such as most emigrants.

†Another way of saying ‘forcibly displaced’ – this process, which took place over a period of 100 years in the 18th and 19th centuries, is now referrred to as the Highland Clearances.

Matthew Crampton’s book, Human Cargo: Stories and Songs of Emigration, Slavery and Transportation, is available for £10 – more info here. The pictures accompanying this article come from the 50 illustrations in the book.