Archives

26 January, 2018

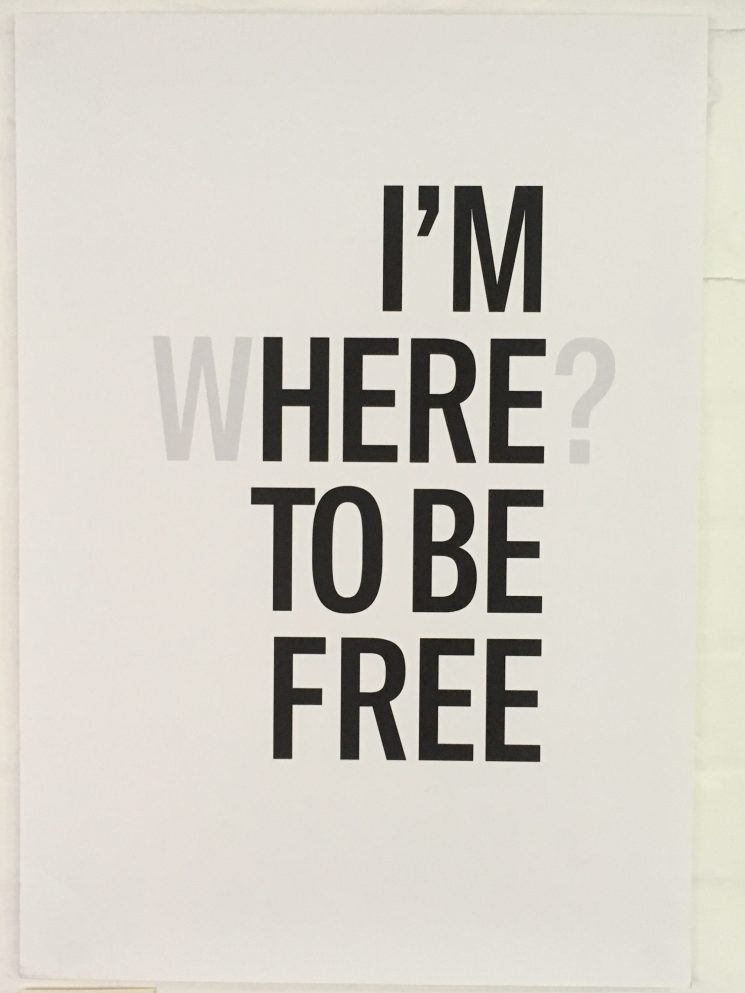

In a collaboration between the Migration Museum Project and the University of Hertfordshire, second-year graphic design and illustration students were tasked with designing a poster in response to the question: ‘What does migration mean in the UK today?’ Chosen by Curator Sue McAlpine, a selection of these posters is currently on display along the stairwell and entrance corridor to the Migration Museum at The Workshop.

Kerry William Purcell, Senior Lecturer in Design History at the University of Hertfordshire, explains the background to the project as well as presenting some of the posters produced by his students.

Migration Museum Project

—

What does it mean to leave everything behind to start again? What happens when the problems of victimisation, lack of work, or exploitation – the very reasons that compelled one to migrate in the first place – are experienced in a newly adopted country?

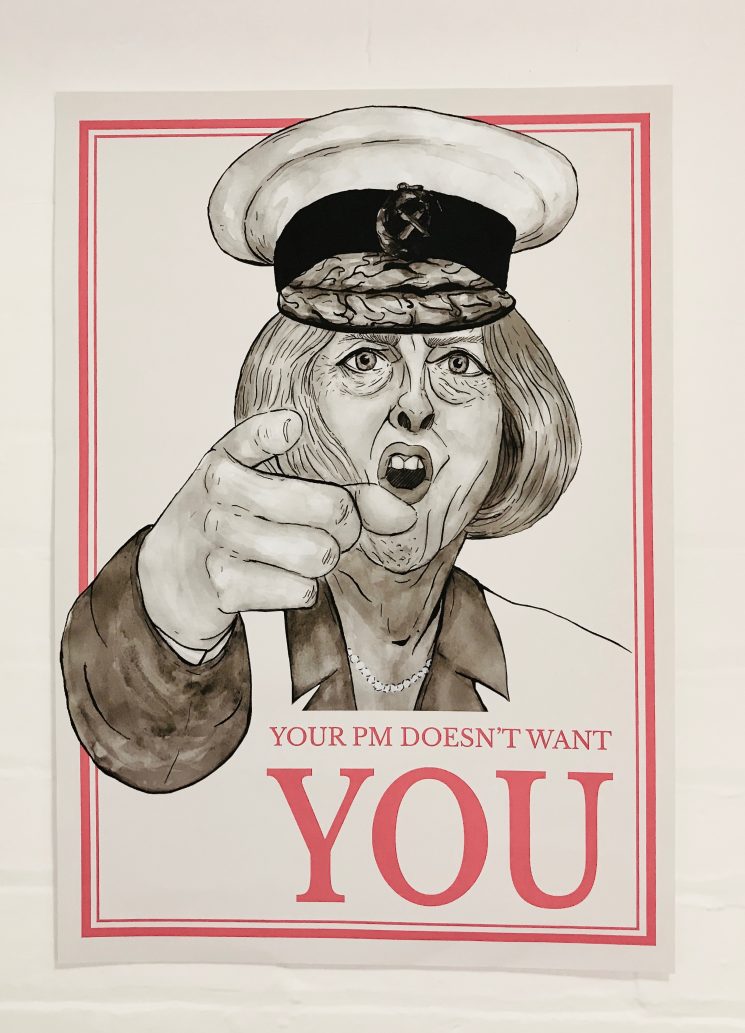

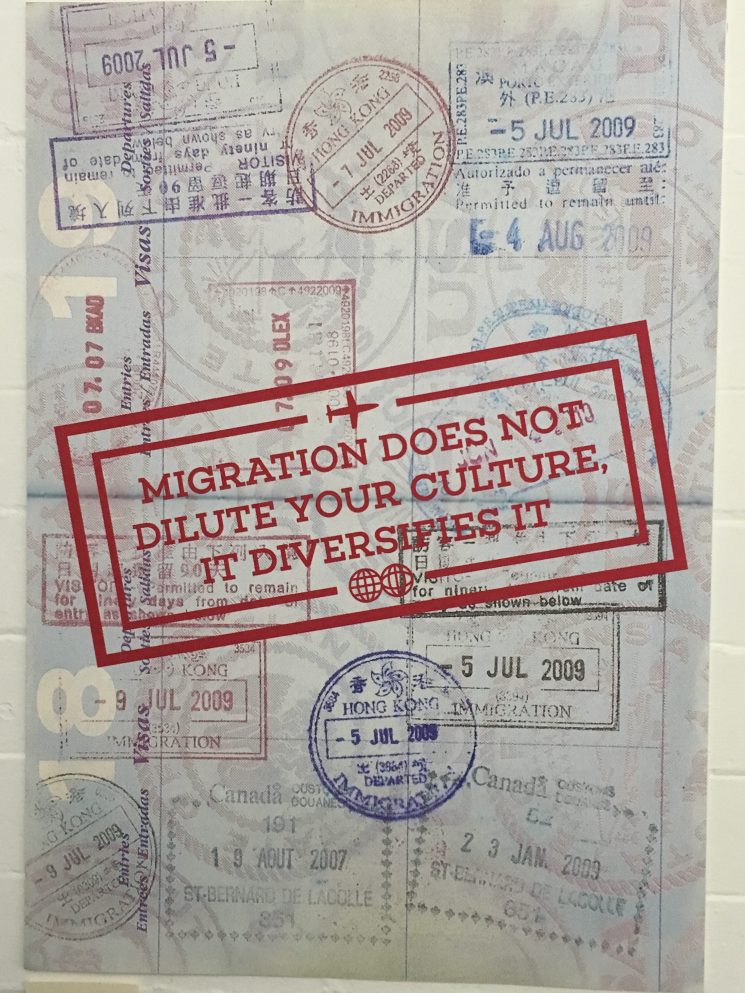

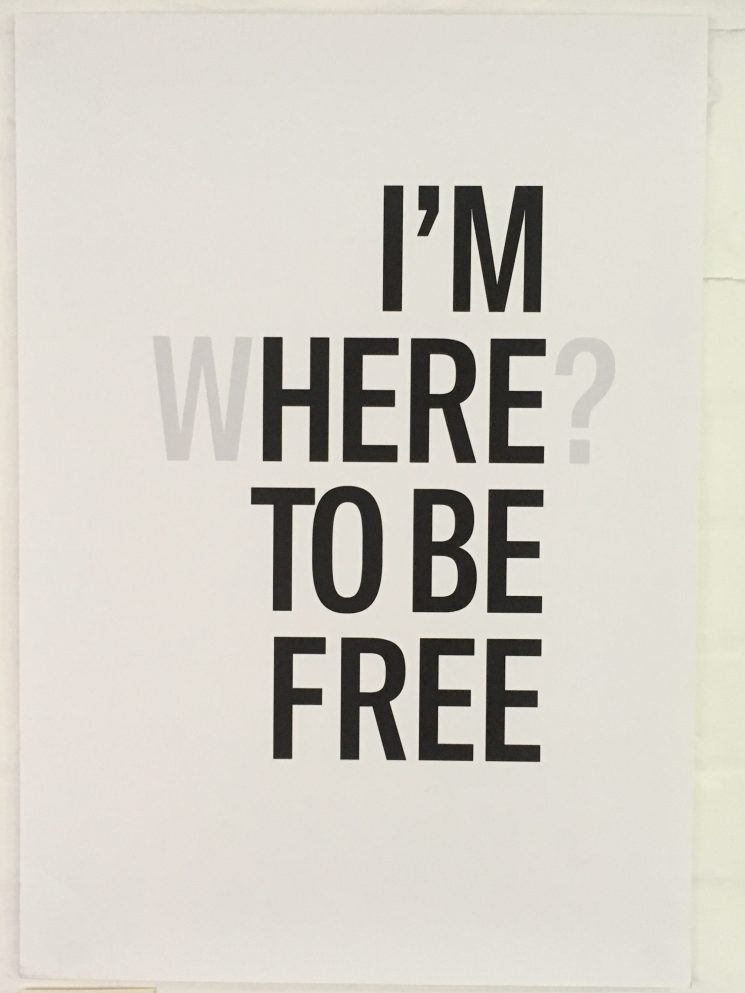

Faced with the question of ‘What does migration mean in the UK today?’, second year University of Hertfordshire (UH) graphic design and illustration students were tasked with representing such issues in a single poster. Working individually, the project ran for two months and was part of a larger brief where the students also wrote essays addressing a range of ethical issues in design.

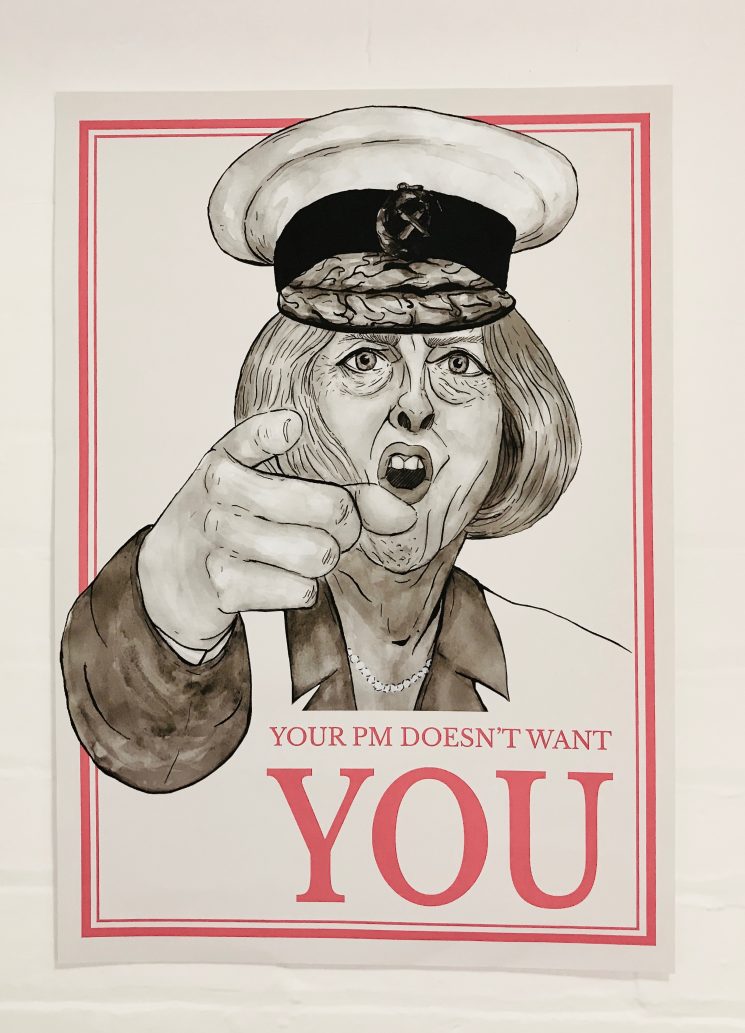

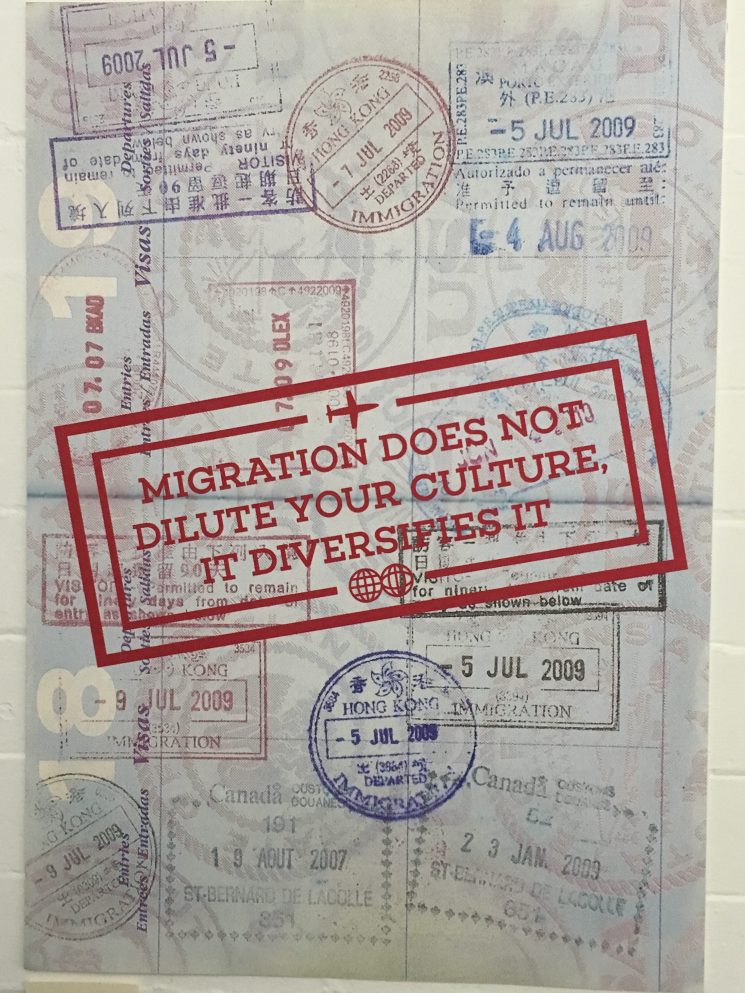

The brief for this work was intentionally broad. And as can be seen from this selection, the outcome was a wide range of responses, from the personal and autobiographical, to news stories, to designs that touch on the aims and ambitions of the Migration Museum itself.

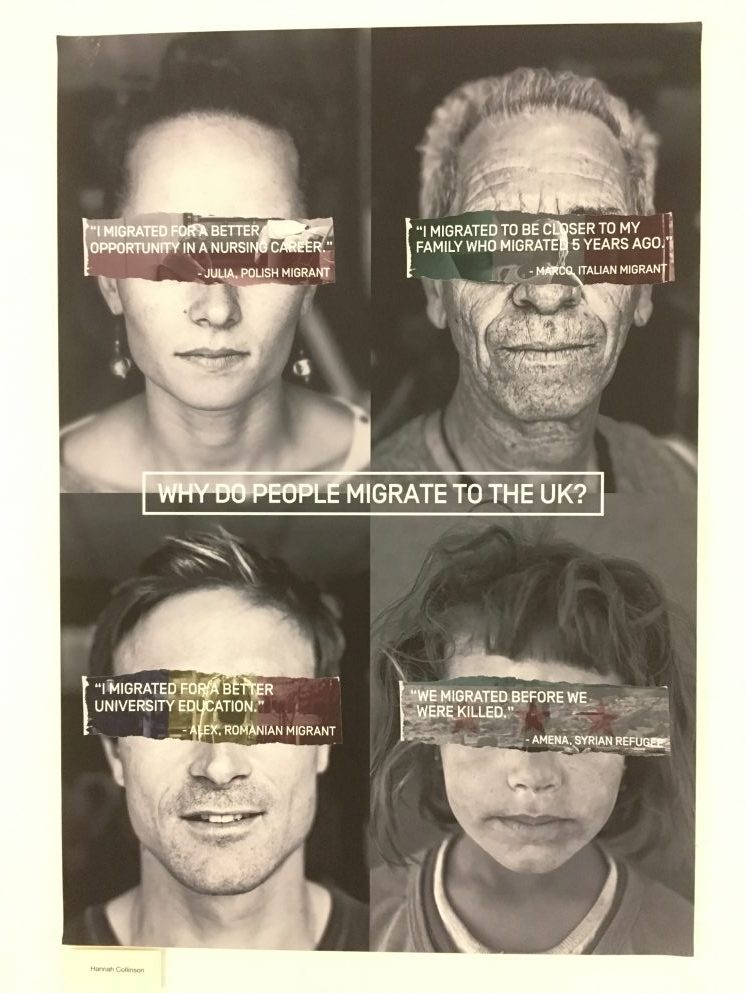

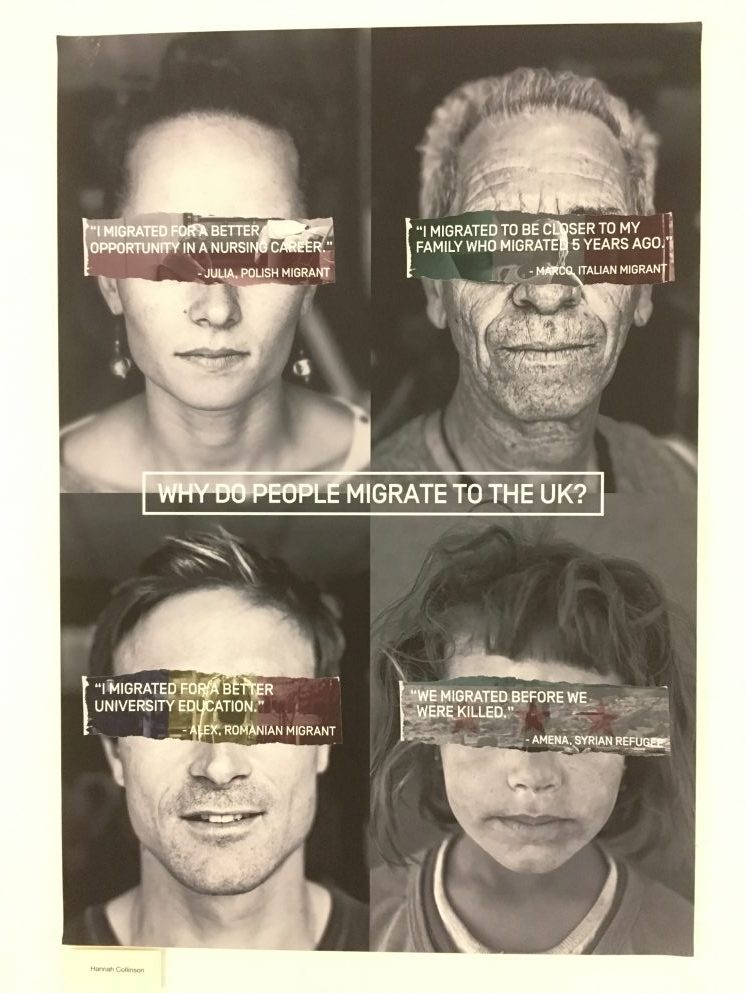

Hannah Collinson

Many UH students are either migrants themselves, or the children/grandchildren of migrants. As such, for some, the project opened a space to speak to family members about their migratory experiences. For others, it was a chance to respond to the dominant tabloid narratives of ‘othering’ that have been so prevalent in recent press coverage of the current ‘migration crisis’.

In this digital age, one can often forget how the poster has long been a vehicle for the dissemination of (mis)information about the subject of migration. Whether as government propaganda, or grass-roots campaigns seeking to challenge the mistreatment of migrants, the poster has the ability to condense a complex range of issues into a single graphic space. As many of these student designs reveal, it still remains a powerful visual tool.

Kerry William Purcell is Senior Lecturer in Design History at the University of Hertforshire and Associate Tutor in Cultural Theory at Birkbeck, University of London

A selection of these posters is currently on display along the stairwell and entrance corridor to the Migration Museum at The Workshop, 26 Lambeth High Street, London SE1 7AG. We are open Wed–Sun 11am–5pm (late opening until 9pm on the last Thursday of each month).

Click here for more information on how to find us

—

Danielle Spokes

Vivian Phang-Xin-Yuan

Michael Gillerton

Rahmel Hewitt-Powell

Victoria Plum

Marta Płaczkowska

22 January, 2018

If you find yourself anywhere near Croydon between now and April 2018, go and visit the Gujarati Yatra exhibition, which is nestled away in the Museum of Croydon and occupies the stairwell, corridor and café of the Clocktower building in which it is housed.1

This exhibition tells the story of the double diaspora of the Gujarati people, many of whom left the westernmost state of India in the 19th century to develop the trade and the industry of ports in the east and south of Africa, before being forced in the 1970s to leave their African homes and communities to find refuge in the UK and other countries. Anyone only partially familiar with the story of this population will find plenty of treasures in the exhibition, which is dominated by the oral and video testimonies of Gujaratis living in Croydon (host to one of the largest Gujarati communities in the country) and other parts of London and the UK, and by objects and artefacts loaned by ordinary people and by academics and historians. These oral histories and personal testimonies clearly shaped the narrative of the exhibition.

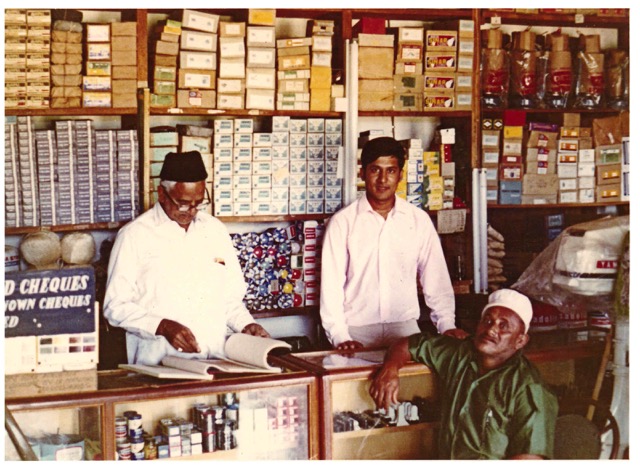

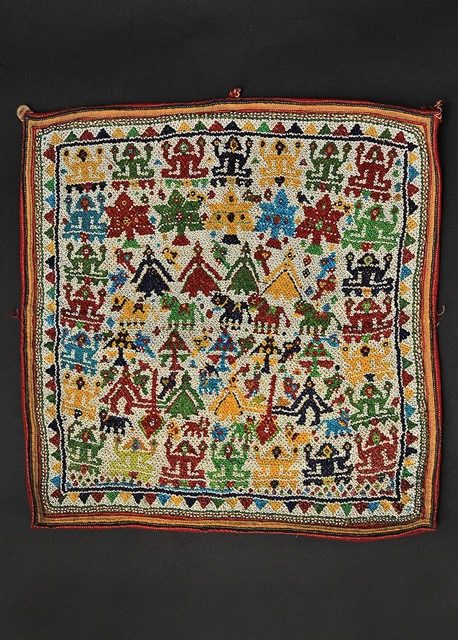

Dukawallah in Uganda.

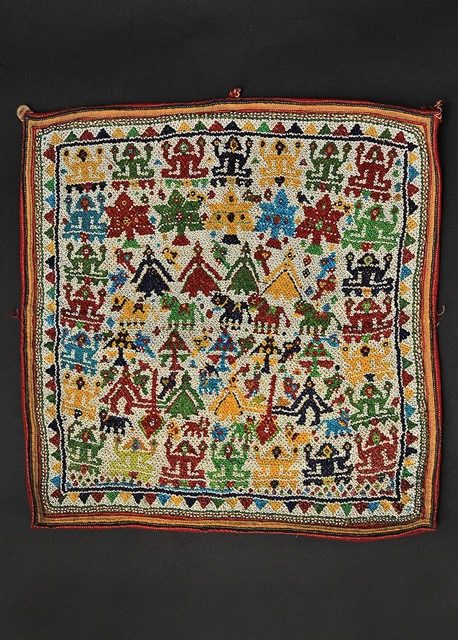

A vibrant display of textiles, metalwork and other materials captures the resilience and the creativity of these displaced Gujarati communities, and shows both how they strove to preserve the art, language, food, literature and religion of their people and also how these were in turn adapted by the countries to which they migrated. It shows how the ‘dukawallah’, who established shops and stores along the east African train line, went on to set up corner shops and stores in Britain and other Western countries, in the process contributing to the change in shop opening hours that eventually led to Sunday trading. It demonstrates how the culture of the people shrugged off differences in religion and belief (the state of Gujarat, while predominantly Hindu, also had significant Muslim, Sikh, Jain and Zoroastrian populations) and how indeed these differences often refashioned cultural templates, which you can see in particular in the evolution of different textile forms. And it reveals – through its stories of everyday racism, the Grunwick strike and the extraordinary success of certain individuals – aspects of migration and settlement that will be familiar to people from different cultural backgrounds.

Beaded square piece.

Intriguingly, from the Migration Museum’s point of view, many of the decisions made by the two curators of the exhibition, Rolf Killius and Lata Desai, match decisions made in our own exhibitions – and vindicate the approach! Not only have almost all the artefacts on display been loaned to the exhibition by ordinary citizens, but the examples of embroidery and other stitchwork adorning the walls downstairs in the cafe area are also all the product of people who have attended the workshops run as part of the overall exhibition. Many of these pieces have been produced by people who had not stitched anything before attending the workshop. In addition, the oral testimonies that accompany the individual displays represent precisely the kind of spoken record that we aim to develop in our own Migration Museum.

Rajkot Patodu sari.

Gujarati Yatra has received Heritage Lottery Funding allowing it, after April, to migrate to a digital format so that it will be available for a further seven years as an online collection. All oral history interviews, the edited films, photographs and texts will go online on a dedicated website: www.gujaratiyatra.com

The whole display is a wonderful, colourful, affirmative account of the ability of a people to navigate its double diaspora and to keep intact its spirit and its sense of cultural identity. We urge you to go and see it!

1As part of the same exhibition, Croydon Now Gallery showcases oral histories and travelling objects (to 14 April 2018), and there is a sari exhibition in the Clocktower atrium (to 26 February 2018) and an embroidery exhibition in the Clocktower Café (to 27 January 2018).

Gujarati Yatra is open until 14 April February in Croydon Now Gallery, and a season of events has been woven around its six-month residency – family days of art and crafts, talks, film screenings, literary events and dance productions – all designed to show how the Gujarati identity is maintained in the UK. The curators are currently contacting other museums and community organisations in order to tour the exhibition to other places in the UK.

26 March, 2019

Boys playing with discarded pram wheels, 1988.

21 December, 2017

The festive season is upon us. According to experts commenting on the subject in magazines and newspapers, it could equally be called the arguing season. A friend in an early Christmas party bemoaned the arrival of her in-laws, bringing with them different opinions on Brexit and other political issues that, sooner or later, led to uncomfortably heated confrontations.

And just two days ago, what started as a really interesting discussion in our house – on why so many men failed to recognise that rape and wolf-whistling were on the same continuum, on the way in which power relationships skewed jokes and banter, on whether it was ever acceptable to use racial identity to comic effect – morphed into one of those confrontational exchanges from which at times it feels there’s no coming back.

© Scott and Borgman

And it got me thinking, in an end-of-year valedictory fashion, why it was that discussions, arguments and debates these days so quickly became polarised, and the position taken by the opposing individuals so firmly entrenched. (And is it just ‘these days’? Was it always like this?) What starts out as an exchange of views transmutes into an exchange of fire, and people’s positions end up ludicrously exaggerated – as Hella Eckardt’s recent blog illustrated, in relation to Roman Britain. People at either end of the spectrum insist on the absolute truth of their position with a strident vehemence that doesn’t represent the reality – which is that all of us, bar the most extreme fanatics, recognise the possibility of alternative positions even when firmly convinced of our own. But rather than examine the evidence, listen to whether the other speaker brings something new to the debate that might cause us to reconsider, it suddenly seems more important at any cost to win this argument, to prove that our position is right and the other’s wrong.

Is this failure to discuss and the associated need to win spawned by the structure of our institutions? The adversarial position is hard-wired into our legal system, for example, and also into Parliament (at least, certainly the House of Commons); it used to, and may still, be at the heart of university research and debate; and it’s of course the basis of all sporting activity. It’s clearly not unique to the UK (the US displays it in spades) but is it uniquely Anglo-Saxon, or European, or Western? Are there countries and cultures where winning an argument is less important than hearing what everyone has to say?

These questions lie at the heart of what we are attempting with the Migration Museum. If our concern was to win the argument (whatever that might be) or show other people the error of their ways, we would, rightly, be doomed to failure and unworthy of support. But what we are wanting to do is to create a space where people can debate issues of paramount importance without automatically taking up tired and predictable positions and seeing who can shout the loudest. Our strapline – all our stories – was chosen to reflect both the fact that if you scratch the surface of anyone’s family history in Britain, you will find a migration story, but also, crucially, the recognition that everyone has a say in this matter and all have a right to be listened to, even if some might find their views unacceptable.

It’s not a new year’s resolution, because it’s been the nub of what we’ve been doing since the beginning, but listening and allowing the spectrum of opinions to be heard without it all descending into the weary Twitterati scrimmage of rancour and animosity – that’s what we’ll continue to do in 2018. With Brexit, Trump and other factors casting their divisive, polarising shadow, it seems more important than ever. So, if you’re raising a glass over this festive period, here’s to listening, not fighting.

To all our readers and followers, have a really good break over the festive period, and see you again in the New Year.