Archives

27 February, 2016

Last year we were fortunate to contribute to a major exhibition, Adopting Britain, at the Southbank Centre, exploring 70 years of migration to the UK. Among the wonderfully varied projects featured in the exhibition, a set of photographs from Northern Ireland caught our eye. Beautifully composed against a simple dark backdrop, highlighting the diversity of people living in Belfast, the images and themes from the Belonging Project resonated strongly with us. We are delighted to feature some of the photographs from the project, which is a collaboration between the Migrant Centre NI and photographer Laurence Gibson. Laurence shares the idea behind the project below.

“I am a Vietnamese refugee. I was in this ship, which carried 295 passengers. The vessel maximum capacity was supposed to accommodate a hundred passengers only … the condition on the ship was horrific. There was no fresh water and a suffocating odour filled out the whole ship. Sometimes, when sea waves hit the ship, there was no shelter and we all got soaked.” Photograph of San Dinh © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

The Belonging Project came about when I was working with a journalist on a story on modern-day slavery. On contacting the Migrant Centre of Northern Ireland, I met with Jolena Flett. It became quickly apparent through our conversation that there was much more to migrants’ stories than abusive working conditions, although these are important to highlight. Jolene asked me to consider whether the story we were running represented anything ‘new’ to the public’s front page. The phrase that kept on coming up in conversation was “these people are human beings” – with the current crisis and migration from Syria, I think this is often forgotten.

After the meeting with Jolena I went away to think about how better to portray the lives of migrants coming to our country. Having grown up in Northern Ireland, I have seen an enormous change in the population, with new cultures coming in. It’s fantastic. I came up with the concept of the Belonging Project as a way of personalising the topic of migration, to remind the public that migrants are not a cohesive group aiming to invade the country and assimilate the population.“I had a good life in my home country,” “I cried for the first two weeks,” “I was heavily pregnant with no way of communicating to the doctors and nurses that surrounded me,” “When I am in Portugal, I miss Northern Ireland; when I am in Northern Ireland, I miss Portugal.” These reflections are vital to humanising the individuals who choose to move to our country.

All of our participants have experienced migration but in very different ways, with each having their own reason for moving to Northern Ireland. The common assumption in the UK that migration is a shift from a poor situation to a much-improved one is really quite presumptuous. We have recorded many stories of individuals who left happy lives with supportive friends, family, and jobs to move to uncertain situations. Why did they leave? In some cases, their partner or parents needed to move for study or work. Or perhaps their decision was shaped by the encouragement of friends who were already in Northern Ireland. Their reasons for moving are varied, from fleeing conflict to simply looking for a better life for their family. Let’s start treating these people as individuals and not numbers on a government statistics table. Just like those of us born here, migrants are not all good and not all bad. But before we batten down the hatches, let’s find out who they really are.

Public education is obviously paramount to our mission, but there are many seemingly smaller effects that aren’t so obvious. The simple act of allowing people to tell their stories and celebrate them in a public context is an enormous opportunity. From very humble beginnings of five portraits in a makeshift gallery space in the Migrant Centre offices, we have gone to a touring exhibition around Northern Ireland, and even to the Southbank Centre in London as part of their Adopting Britain exhibition. Libraries NI have provided a vital role in providing us with exhibition space in the community around Northern Ireland, having been the organisation to first discover us in our makeshift gallery almost two years ago. Currently, the Belonging Project is looking into the possibility of working in conjunction with a local boxing academy to show boxing as a cross-cultural unifier between migrant and non-migrant communities. I am so pleased to see the project continuing in a new and sustainable direction.

Laurence Gibson is currently based in London and specialises in partnering with a variety of charitable and commercial organisations to produce innovative still photographic series, often with audio accompaniments. http://laurencegibson.co.uk/

If you would like to see the Belonging Project in person, upcoming events include portrait exhibitions at the Belfast Waterstones bookstore from 25 February to 3 March and UNISON Northern Ireland from 1 to 11 March. More information on the project is available on their website: http://www.thebelongingproject.org/

“What helped me a lot was football: it basically helped me integrate into the local community because I was playing for local teams and getting to meet people. There’s no language barrier in football: everyone turns up and runs behind the ball and kicks it. There’s no, “You have to speak English”. It’s a great tool to break barriers.” Aruna, Guinea Bissau & Portugal/Northern Ireland © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

“My mother used to read this, to me and my younger brother … this has very strong memories of my childhood, and when I felt happy and safe with my family. It’s important for me to pass it on, some of the information and storytelling, to friends and friends’ children – that is why I kept it all these years.” Cornelia, Greece/Northern Ireland © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

![“The object which I brought today is called mbira, it’s a Zimbabwean musical instrument which was made during the early 1880s. It’s a cultural musical instrument, played at cultural celebrations, gatherings, and also can be recorded with any genre of music. This object is important to me because it reminds me [of] back home and [because] it’s a true instrument of Zimbabwe, only made in Zimbabwe” –Everson, Zimbabwe](http://migrationmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/everson-zimbabwe.jpeg)

“The object which I brought today is called mbira; it’s a Zimbabwean musical instrument which was made during the early 1880s. It’s a cultural musical instrument, played at cultural celebrations, gatherings, and also can be recorded with any genre of music. This object is important to me because it reminds me [of] back home and [because] it’s a true instrument of Zimbabwe, only made in Zimbabwe.” Everson, Zimbabwe © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

“So I came over to Broughshane up north. I just fell in love with the place. Just felt home. One of my children said, ‘Mommy, this feels like home.’ That was very touching because that was like a message to say – this is what your children want. You know, follow your dreams, follow your children’s dreams.” Maria, Angola & Portugal/Northern Ireland © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

“I didn’t bring much with me when I left Portugal. I didn’t bring much. I put a tile in the suitcase I brought with me; I have it here, with the emblem of the city of Beja. I brought these tiles with the emblem of the city where I was born.” Luis, Portugal/Northern Ireland © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

“I remember apartheid like yesterday; the thing that clings to me even why I think about it is the smells. The tear gas smells that always caught the back of your throat and the sounds of the sirens.” Nandi, South Africa/Northern Ireland © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

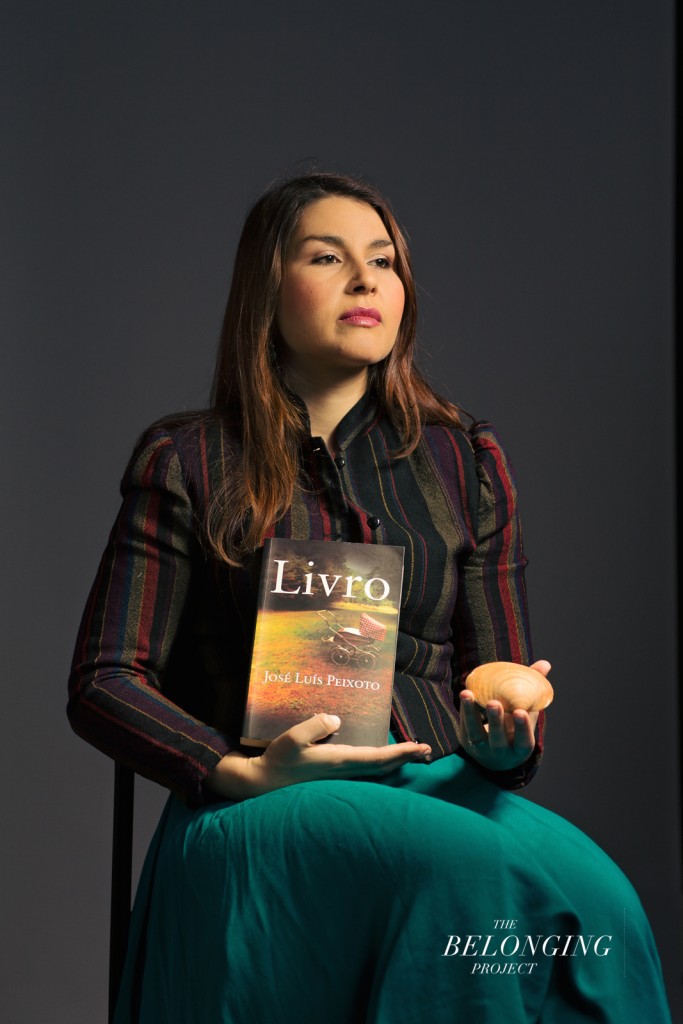

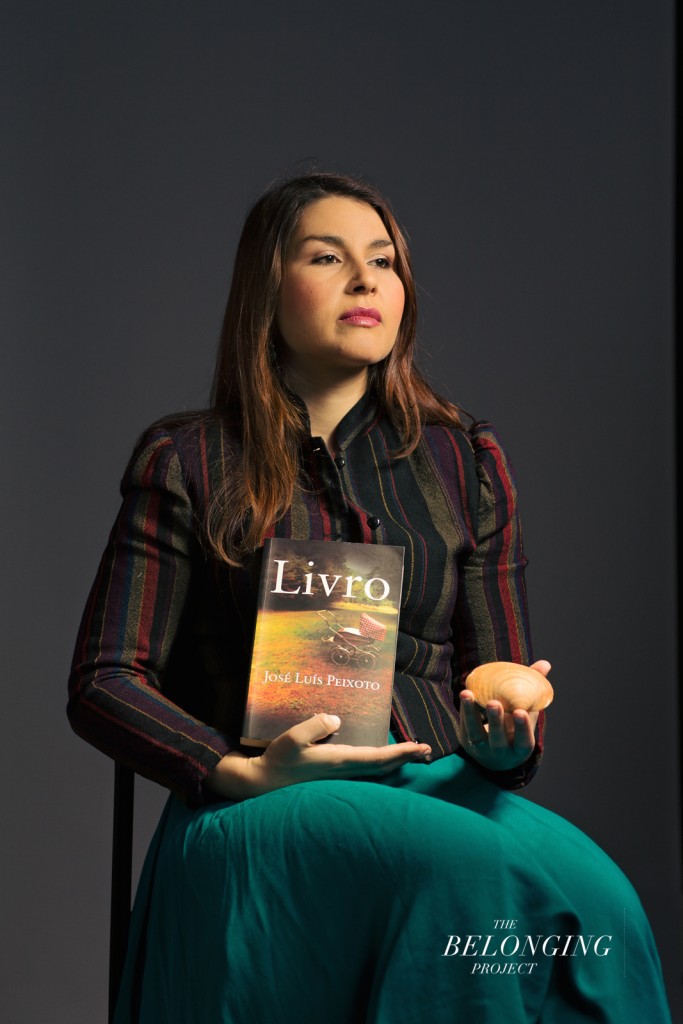

“I brought a book which is from one of my favorite writers in Portugal … it tells this story which is quite different from my own story, but nevertheless the feelings of a migrant person are the same, which is: you feel always split between two worlds and two countries, and if you’re there you want to be here, and if you’re here you want to be there. That’s very much in the book, and I relate to that.” Raquel, Portugal/Northern Ireland © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

“As a migrant, I think every migrant would like to feel loved, accepted and appreciated in the country that they go to. And I too wanted to feel loved in the country that I came to, in Northern Ireland. And yes, I am different – my language is different, my colour is different, my values are different, my culture is different. But love me anyway.” Sangeetha, India/Northern Ireland © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

![[Why did you choose Ireland?] "I don’t know- maybe Ireland chose us" –Plamena, Bulgaria/Northern Ireland](http://migrationmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/plamena-bulgaria.jpeg)

[Why did you choose Ireland?] “I don’t know – maybe Ireland chose us.” Plamena, Bulgaria/Northern Ireland © Laurence Gibson, all rights reserved

Lampedusa’s boat “graveyard”. When this photo was taken, more than 50,000 people had arrived by boat. All the boats come from Libya after a journey that lasts between two and four days. This is just the last leg of a migration journey that sometimes lasts years. Once on land, migrants are identified by the police and kept inside the CPSA (Centro Primo Soccorso Accoglienza, or first aid centre) for a few days and then redirected into another centre, where they can stay longer while their futures are being decided. Some of them get asylum and others are sent back home. © Christian Sinibaldi

The journey is an essential part of the migration experience, but where does it begin and where does it end? Long before a person steps on a plane or boat, a set of cultural cues, laws and regulations have already influenced that journey. And arrival in a new place is hardly the end, for gaining the legal right to settle is a prolonged journey in itself.

To delve deeper into these questions, the Migration Museum Project recently hosted a panel discussion in partnership with Garden Court Chambers, London. The evening featured Kathryn Cronin, head of chambers at Garden Court; Robin Cohen, principal investigator, Oxford Diasporas; and David Chirico, barrister at 1 Pump Court. All spoke about different aspects of the migration journey.

The talks were complemented by an exhibition of images by Christian Sinibaldi and Chris Barrett, photographers documenting the experiences of migrants in Lampedusa and Calais, respectively. A selection of these images are featured below.

The Journey in Cultural Perspective

The idea of the ‘journey’ has permeated migration narratives throughout history. As Robin Cohen explained in his rapid survey, literature is filled with stories of great journeys, from Don Quixote’s quest for adventure to King Arthur’s search for the Holy Grail. Religious texts from the Islamic, Jewish and Christian traditions also feature long journeys in search of promised lands.

Journeys have carried varied connotations depending on the political and cultural context. During the project of nation building in the 19th century, arduous journeys served to confirm the heroic and pioneering nature of the migrants making them. In more contemporary times, similar sea journeys by migrants seeking asylum in Europe dominate headlines, but are tainted with associations of illegality and criminality.

On a more personal level, journeys have a powerful effect on the formation of identities. Professor Cohen argued that journeys are transformative because they allow you to meet new people, who may be ethnically and generationally different from you, and these encounters often result in a new, shared identity.

Journey Controls – past and present

In today’s world it is hard to imagine a time when the movement of people was largely unregulated, yet Britain’s immigration procedures until the 19th century were indeed relatively relaxed. “In the debates of the free movement arrangements in the EU, we tend to forget that the first significant free movement arrangement was the British Commonwealth,” Kathryn Cronin explained. Any person who was born or naturalised in the British Commonwealth was free to move anywhere within its member nations. This primarily served to assist those moving out of Britain, to places such as Australia, to establish new lives and to transport slaves and indentured workers to various parts of the Commonwealth. All of the mechanisms for journey control we have today essentially began in the 19th century, as an unintended consequence of Empire.

Kathryn Cronin argued that the decline of this free trade system started because Chinese and Indian subjects of the British Empire wanted to migrate freely. This led to carrier sanctions, i.e. fines on sea captains carrying Chinese or Indian subjects, and quotas on ships coming from parts of Asia. Individual countries developed strategies to regulate migration through policies such as the “single journey” in Canada, whereby entry was permitted to those who entered the country without stopping anywhere else. If you came from India, you would certainly have to stop somewhere in between and would therefore be denied entry at the port of arrival. In Australia, a policy allowed officials to test immigrants in any language of their choosing, leading to cases where, for example, a left-wing anarchist German immigrant was tested in Scottish Gaelic!

Fast forward to the establishment of the European Union, where mechanisms of journey controls continue to define which migrants are welcome and which are not. The Dublin Regulation, in particular, today plays an important part in deciding how EU member nations examine applications from asylum seekers. David Chirico explained that, according to the Dublin Regulation, the first place where you land is generally the place responsible for your asylum case. In the present context, this means Greece, Italy, Turkey, Bulgaria, Cyprus and Malta. While well intentioned, this arrangement also allows many European countries to divest themselves of responsibilities for migrants, which in turn has led to the ‘crisis’ we face today.

The Legal Journey

David Chirico, who represents several asylum seekers in Britain, shared the stories of some who, having made the journey to Europe, nonetheless find themselves in limbo, thrust into another long journey for legal status. H, an Iraqi Kurd, is one such person. His brother was murdered in front of him by ISIS, and he lost contact with his parents. His family members arranged for him to come to Europe, and he travelled in a van to Bulgaria.

“His first experience of safety in Europe was being pulled out of a van, forced to lie flat on the road, while Bulgarian police officers fired bullets over his head, prodded at him with the end of a gun, kicked him. He was then put in a police cell with 15 other people for three days, allowed to use the toilet once a day. After three days he was told some things in Bulgarian, which he didn’t understand. He signed something that was an asylum claim. He was then locked up for two months with 20 people with one toilet between them. After two months, he was put out on the streets of Bulgaria, where he managed to re-contact his agent, whom he paid to take him somewhere safer. Two weeks later he was detained in the UK. He was released and is now living with his cousin, who doesn’t let him out of his sight because he thinks he will kill himself. He is visibly falling apart. He doesn’t know if the worst thing that happened to him was losing his whole family in Iraqi Kurdistan or living in limbo in the UK.”

These journeys, Kathryn Cronin explained, in addition to being traumatising events for the people making them, are very significant in the legal case of the refugee. “In order to represent clients, we need to have a sense of where they’ve come from. For those of us representing trafficking victims, refugees, the journey is everything.” Officials seek to discredit asylum seekers if they are seen to have taken the wrong path to the country where they are seeking asylum. And if a person cannot fully recollect the journey, they are taken to be lacking credibility.

Robin Cohen questioned whether these migration policies are meant to actually control migration or are performative, i.e. they are only meant to pretend to control migration. An equal number of migrants are involved in a performance, he argued, deciding which narrative works and which doesn’t because they feel the need to have a script. “It’s a high level of performance and low level of reality.”

The panelists touched upon many facets of the migration journey in the context of personal identity, immigration controls and legal procedures, which were further explored through a screening of Sue Clayton’s film Hamedullah: The Road Home. Sue Clayton joined us to answer audience questions about the film, which charts the forced removal to Kabul of a young Afghan who had sought asylum in the UK, in his own words and pictures.

We plan on exploring many of the themes brought up during this discussion through events and exhibitions this year. Please join our mailing list at http://eepurl.com/tfpRP to receive updates.

Migrant camp in Calais © Chris Barrett

Sign posted in Calais © Chris Barrett

Migrant settlement in Lampedusa © Christian Sinibaldi

© Christian Sinibaldi

© Christian Sinibaldi

Our last blog looked at the huge exodus of British citizens in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, when 2 million people left the UK to seek new lives in Canada, the USA, Australia and elsewhere. Emigration continues to be an important part of the migration story in Britain, and currently an estimated 5 million British citizens live abroad. That’s 7–8 per cent of the UK population. The European country with the largest British population is Spain, with an estimated 700,000 British emigrants.

Charlie Clift is a British portrait photographer living in London. He has dangled CEOs upside down, got shouted at by political leaders, waded up to his chest in floodwaters, smeared paint on art dealers’ faces and poured pints for dogs. All of it to make great photographs. He’s worked with the likes of The Sunday Times Magazine, The Independent, Samsung and AXA. His project Brits Abroad, featuring portraits of British emigrants living in Europe, was born out of a desire to change the current immigration debate in the UK by reminding people that Brits are immigrants, too.

Simon owns a Caribbean themed bar on Fuengirola beachfront and enjoys the relaxed lifestyle of the area. He moved to Spain for medical reasons, because the warm climate helps alleviate his arthritis. © Charlie Clift

My interest in migration came from a frustration with the way migration into the UK was being talked about in the British media. Instead of viewing it as a human subject, it is often spoken about using statistics and stereotypes – when in fact every person’s journey to a new country is unique and personal. I wanted to show this to a British audience and couldn’t think of a better way to do this than to look at the lives of British people who had moved to live abroad. Every person I photographed lived a different life in Spain: some did live the stereotypical ‘retired and moved for sunshine’ type of lives, but many did not – from those who struggled to speak Spanish, and therefore to integrate, to those who had married Spaniards and brought up a family there. Each was a unique story.

Before setting off to Spain I started asking just about everyone I met if they knew a Brit who lived in Spain. This led me down a lot of interesting paths. Of course, once you start to find people in the area, they recommend others who may be interested in taking part in the project. I also thought of certain things which were really British and researched to see if they existed in Spain – for example, I found the Javier Bowls Club when I looked for the very British hobby of lawn bowls. Eventually – after many hours on Skype, on Google and talking to people – I found a wide group which I thought would show the diversity of the Brits in Spain.

For almost all of my sitters, moving abroad was the biggest change they have ever experienced in their life. It is not something people do lightly and is often something that defines them and which they feel is an important part of their character. I also found there was a unique ‘Britishness’ running through all the people I photographed, regardless of how much they had integrated into the Spanish way of life. I don’t think people lose their origins – it is part of who we are and will always be with us.

People often talk about migration into the UK and forget that Brits are immigrants too. I hope that by showing these people’s stories I will make people think twice about immigration into the UK, or at least see the discussion from a different viewpoint.

With a referendum about Britain’s membership of the EU on the way I thought there would be no better time to remind everyone in the UK just how many British people are living in Europe – so I am currently expanding the project to include many other EU countries. I’ve just got back from Denmark, Sweden and Estonia, and I hope to add four or five more countries in early 2016. By the end of the project I will have a body of work showing the massive variety of lifestyles that exist within Europe that I hope will help people see migration from a new angle.

Francesca was born in Spain and is schooled in the Spanish education system; she is also a British citizen. She enjoys chocolate ice-lollies from the Iceland store that her mother occasionally visits to purchase British goods. © Charlie Clift

Sean runs a traditional British fish and chip shop by the beach in Fuengirola. The majority of his customers are British holiday makers or expatriates and he serves chips made from imported British Maris Piper potatoes. © Charlie Clift

Carole regularly plays bowls at the Javea Green Bowls Club, which consists almost entirely of British members. She loves living in Spain and doesn’t want to move but is frustrated that she can no longer vote in British parliamentary elections. © Charlie Clift

Reggie works at an English language newspaper that her husband owns. She likes the Spanish pace of life but has not learnt to speak the language and thus struggles to integrate with locals. © Charlie Clift

David Salgo is a musician who retired to Spain. He enjoys living in a typical Spanish village and plays golf regularly with friends, many of whom are also expatriates. © Charlie Clift

David is a sculptor who works in his home in the mountains. He moved to Spain 46 years ago after learning to speak Spanish on a long motorcycle trip through South America. © Charlie Clift

Paul runs an English language newspaper called The Courier from an office in Torrevieja. He moved to Spain to escape the busy life he had in London working for News International. © Charlie Clift

Joyti lives and works in a community project in the desert named Sunseed Desert Technology. She enjoys living a sustainable life and move to Spain because it is where the project is based. © Charlie Clift

Stacey runs a charity to care for and re-home unwanted dogs. Her house is full of donated goods to sell to raise money. In her spare time she plays darts in a local expatriate league and looks after her four cats. © Charlie Clift

Linda works cleaning holiday villas to pay her bills and rent. She likes being able to have an outdoor life 8–9 months of the year but misses being able to watch her grandchildren grow up in England. © Charlie Clift

Charlie Clift’s photography may be viewed on his website – charliecliftphotography.com –where there is more information on his Brits Abroad project.

1 December, 2015

The four panellists for ‘Migrant Haven’ (l to r): Stanislas Yassukovich, Kathleen Burk, Caroline Shaw and David Kynaston

What contribution have migrants made to the City of London, the financial powerhouse of the United Kingdom? And what role do they continue to play in shaping London’s financial institutions?

These questions were the focus of our latest Great Minds event, City of London: Migrant Haven, hosted by Schroders on 16 November 2015. The event chaired by eminent historian David Kynaston featured historical and personal perspectives on migrants who have left their mark on the City from the 17th century to the present day. The panel of speakers consisted of Caroline Shaw, Archivist at the Schroder Archive; Kathleen Burk, Professor of Modern and Contemporary History at University College London; and Stanislas Yassukovich, widely regarded as one of the architects of the international capital market and previously CEO at European Banking Group.

18th and 19th Century City of London

David Kynaston, author of the four-volume series The City of London, highlighted that the City has always been open to people coming from abroad to work, but that migration truly picked up pace in the late 17th century. This is reflected in the history of the Bank of England, a quarter of whose original board of directors at its founding in 1694 were of Huguenot heritage – including the first Governor of the Bank, John Houblon.

Sir John Houblon was a Huguenot who served as the first Governor of the Bank of England

By the early 18th century, the City of London was a visibly cosmopolitan financial capital. Joseph Addison wrote in The Spectator in 1711,

THERE is no place in the town which I so much love to frequent as the Royal Exchange. It gives me a secret satisfaction, and in some measure, gratifies my vanity, as I am an Englishman, to see so rich an assembly of countrymen and foreigners consulting together upon the private business of mankind, and making this metropolis a kind of emporium for the whole earth … sometimes I am justled among a body of Armenians: sometimes I am lost in a crowd of Jews; and sometimes make one in a group of Dutchmen. I am a Dane, Swede, or Frenchman at different times; or rather fancy myself like the old philosopher, who upon being asked what countryman he was, replied, that he was a citizen of the world.

According to David Kynaston, the 19th century City of London owes much to three game changers, all of them German Jewish immigrants: Nathan Rothschild, Ernest Cassel and Siegmund Warburg. The latter was instrumental in the development of the Eurobond, which marked the City’s revival as international financial centre. Commenting on the overwhelming internationalism in Canary Wharf today, Kynaston also left us with a provocative question about a potential downside to all this migration:

Has there been a ‘Wimbledon-isation’ of the City, i.e. rather like the tennis tournament, we provide the venue but we no longer provide the champions?

The German Connection

Caroline Shaw, Archivist at the Schroder Archive, explored the contributions of the Hanseatic Schroder family to the UK banking system in the 19th and 20th centuries. Schroders was founded in London by two brothers, Johann Friedrich and Johann Heinrich Schroder, in the early 1800s and their strong links to Germany were a significant factor in the firm’s early development. But, by the mid-19th century, the firm diversified into areas – including bond issuing and, more interestingly, taking on agency for the distribution of Peruvian guano – that were less dependent on the German connection and made it one of the most prominent merchant banks in the City.

The First World War brought the ‘nationality’ of the firm into question – the senior partner of the firm, Baron Bruno, was in immediate danger of internment as an enemy alien and the firm in imminent danger of seizure as enemy property. Not only that, but £4 million, more than the firm’s entire capital, was tied up in obligations accepted on behalf of German and Austrian clients.

The outbreak of the First World War brought the German origins of Schroders into sharp relief.

Schroders was deemed ‘too big to fail’, and the Bank of England lobbied intensively to save the firm. Despite the anti-German sentiment of the war years, Schroders had by that point “entered into the City’s cosmopolitan embrace, and was part of the City’s flows of commerce and capital”. As Caroline Shaw argued,

[Schroders] may indeed have been ‘too big to fail’ but I think we can also usefully see it as having been ‘too integrated to fail’.

Era of American Dominance

Kathleen Burk identified the deregulation of financial markets under the Thatcher government – also known as Big Bang – as the moment in history that opened up an era of dominance of American firms in the City. This had a profound effect on the working culture of the City, leading to longer work hours, shorter lunches and shakier marriages! The Americans were also instrumental in supplanting relationship banking with transactional banking (although the former did not completely disappear) and upending specialisation in markets and financial products with one-stop banking supermarkets.

The aggressive expansion of American business in London required more space for trading rooms and offices, leading first to the building of Broadgate in the mid-1980s, followed by the development of Canary Wharf – the consequence of which being that a large chunk of the City is now outside the City. Finally, Professor Burk argued that the American dominance emphasised, and accelerated, the position of the City of London as separate from the rest of the country, always looking outwards to ensure its survival. With the economic decline of the UK in the 20th century there was a danger that New York would take over. However, the Eurodollar market attracted American money in huge quantities so that, while New York City remains the financial capital of the United States, the City of London, partly due to its dominance in foreign exchange, is now the financial capital of the world.

Kathleen Burk on the American influence: “It could be argued that the influx of American firms, American money, and American business culture saved the City’s bacon.”

A Cosmopolitan Capital

Stanislas Yassukovich, a veteran of the Eurobond market who started in the City in 1961, spoke of his family’s personal experiences in London. He recalled that his Russian émigré father marvelled at the cosmopolitanism of the City of London in the first half of the 20th century. He credits this cosmopolitan culture as a significant reason why London was able to surpass Paris and Amsterdam as the financial capital of the world. Those cities were much more insular, whereas London not only welcomed individuals and skills but also integrated the cultures and ethos of migrants into the City. “Immigration is a key factor to London’s success,” said Yassukovich. He also acknowledged the changing nature of the City and particularly the erosion of its village-like feel, which has historically also made the City cohesive and successful.

Stanislas Yassukovich considers the characteristics that allowed the City of London to thrive.

The panel also engaged in a lively question-and-answer session with the audience that touched on topics such as migrants’ reception outside the City in the places they lived and the UK’s relationship to the EU. At a time when migration is a constant feature in the news, the panel discussion illuminated the long and continuing history of migrants’ contributions to London’s thriving financial institutions.

![“The object which I brought today is called mbira, it’s a Zimbabwean musical instrument which was made during the early 1880s. It’s a cultural musical instrument, played at cultural celebrations, gatherings, and also can be recorded with any genre of music. This object is important to me because it reminds me [of] back home and [because] it’s a true instrument of Zimbabwe, only made in Zimbabwe” –Everson, Zimbabwe](http://migrationmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/everson-zimbabwe.jpeg)

![[Why did you choose Ireland?] "I don’t know- maybe Ireland chose us" –Plamena, Bulgaria/Northern Ireland](http://migrationmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/plamena-bulgaria.jpeg)