Hands-on multiculturalism: learning about everyday diversity in urban England

As Britain’s cities, towns and countryside become more ethnically diverse, it is important that issues of diversity and multiculture are taught in relevant and sensitive ways. In this blog, Katy Bennett and Giles Mohan reflect on their teaching workshop at the Migration Museum Project’s Call Me By My Name exhibition last year and on the research that underpinned it. We will be publishing two further blogs about their workshops with school groups over the next week.

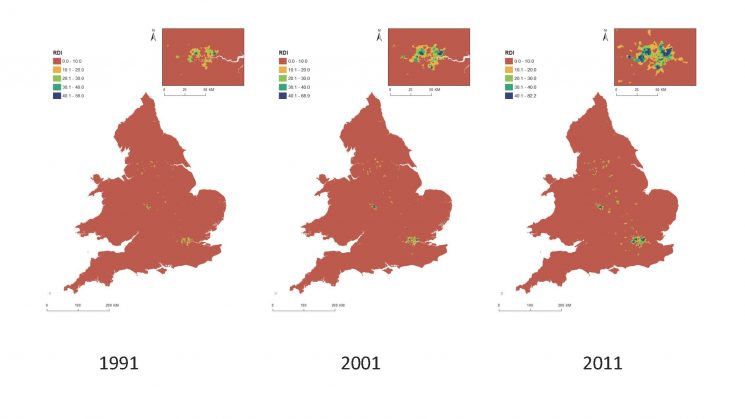

As Britain’s towns and cities become increasingly diverse, teaching about multicultural becomes more and more important. ‘Minority’ groups are found no longer only in large (post-) industrial cities like Manchester or Birmingham but also in smaller urban centres like Boston and Peterborough. The maps show census data which reflects these changes, with the green and blue shadings indicating more diverse areas. The changes from the 1991 map to the 2011 map reveal more areas becoming diverse, and already diverse areas – such as parts of London – becoming even more diverse.

Source: Gemma Catney (2016) ‘The Changing Geographies of Ethnic Diversity in England and Wales, 1991–2011’, Population, Space and Place, Volume 22, Issue 8, 750–65.

The geographies of multiculture have changed and are continually changing, so that all areas, and the schools they contain, need to think about how people engage with cultural diversity and difference. As part of the Migration Museum Project’s Call Me By My Name exhibition in 2016, we ran a teaching workshop to help students think about their own identity and how they identify and relate to others in their daily lives. Our workshop took place in the space of the exhibition, surrounded by photographs, artwork and artefacts that brought into the room personal experiences of migration, refugee camps, loss of home and loved ones and experiences of moving to the UK. Haunting the space were the fake ‘life’ jackets used by migrants and found on beaches, exhibits counting relatives lost in perilous sea crossings and the vulnerability of lives lived in camps, at borders and on the margins of societies.

We began the workshop with Year 8 students by asking them to walk around the room. When we clapped, they had to form into self-selecting groups of four or five (i.e with no intervention from ourselves) and we asked them to draw around both their hands on A4 sheets of plain paper. They then wrote on their left-hand outline words that describe how they see themselves and on their right-hand outline words that they think other people would use to describe them. Next, they were asked to talk in their groups about the words they had used to describe each hand, and how they felt about the words others might use to describe them. After a few minutes of these group discussions, in the course of which we mingled and chatted, a few students stood up to talk about their hand drawings and labelling.

The aim was to open up questions of cultural identity and to think how inadequate words and categories are for capturing complex and shifting identities. One person, for example, labelled themselves as Somalian, from Milton Keynes, and moving from Sweden – and even then they were aware that these labels didn’t really capture who they were but were ways they used to help others position them. When it came to how others might label them, however, they replied ‘African’ or ‘black’. In most cases, there were differences between how people identified themselves and how they thought others would identify them.

We asked the students why they sat with whom they did, because we were also interested in the ways in which groups form. One group of young men were largely of Ghanaian origin and were vocal and confident; other groups were a bit more mixed ethnically and nationally, with only one or two putting themselves forward as spokespeople.

The dynamics of the room were used as a way of thinking about the small-scale geographies of multiculture. While the school body was very mixed ethnically, like many classrooms across the UK, groups sometimes followed particular ethnic and national lines. Most students were used to using ethnic and racial labels like ‘white’ or ‘African’, but were equally aware that these were quite blunt categories which concealed lots of complexity and contradictions.

It is these same everyday ‘micro’-geographies that we explored in a research project called Living Multiculture: the new geographies of ethnic diversity and the changing formations of multiculture in England, which we conducted as part of a team led by Professor Sarah Neal.

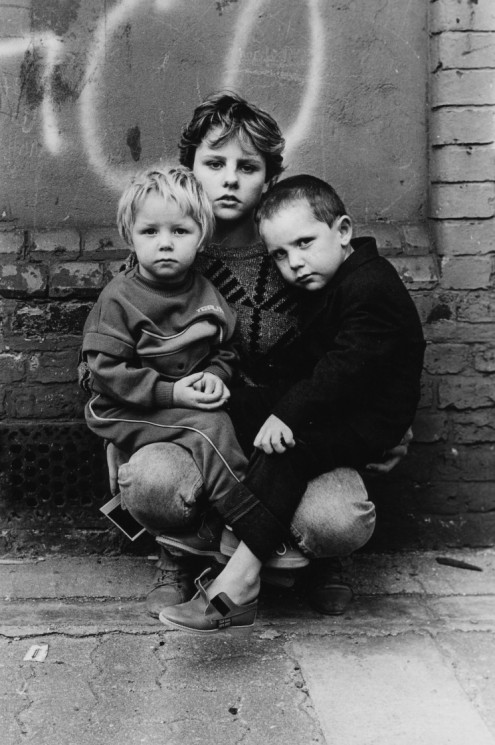

Mural in Hackney, east London. ©Author’s own

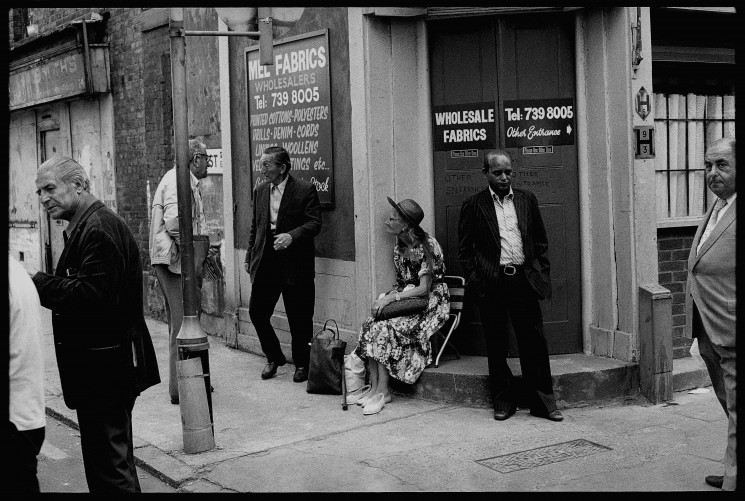

The Living Multiculture project started from the reality of the changing geography of ethnic diversity in contemporary Britain – the patterns shown in the maps above. Places are changing, and we wanted to understand how people understand and live through these changes. We also wanted to examine ‘everyday’ encounters across ethnic difference against the background of the popular image, in the media and among many politicians, that multiculturalism in Britain had ‘failed’ – particularly post-BREXIT – and that cities are riven with segregated neighbourhoods and ethnic and racial tension. It was not that we wanted to turn a blind eye to very real conflicts, but to argue that, for many people, most of the time they rub along. Our main question was ‘How do people live and experience multiculture as part of their everyday lives?’

We studied this question through fieldwork in three areas, each of which represented a different aspect of Britain’s changing ethnic geography.

- Some cities that were already diverse are becoming ‘superdiverse’ with the arrival of new migrant groups. For this group, we chose the Borough of Hackney in London.

- Some ethnic groups that first settled in inner cities are now moving outwards, as their social and economic status improves. For this group, we studied the newly diverse suburb of Oadby in Leicestershire.

- As noted, some large towns and small cities are becoming diverse for the first time – for this, we chose Milton Keynes as an example.

You can find out more on our website and in a new book we have co-authored with the rest of the team, but some of the key findings are:

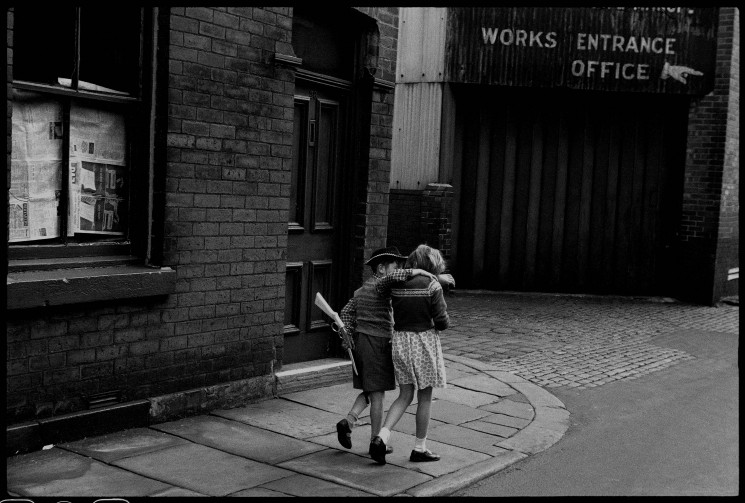

- We studied the places where people gather and mingle – cafes, parks, libraries and colleges. We found that these are important sites for people to be together in quite relaxed and informal ways, even though a lot of thinking and design goes into making them seem informal. For example, in the chain restaurants we studied, it was the informality of the fast-food model that enabled people to rub shoulders in easy ways.

- We also found that ‘things’ and places matter to these relationships. The design of internal college spaces or shopping malls all aided flows of people or encouraged mingling. Mundane things like park benches or car parks were all crucial for allowing people to encounter one another.

- But social skills were also important for living cultural difference. Managing the un/easiness of being thrown together in a room with us and being asked questions about identity involves considerable skills. One such skill students used was knowing how and when to joke with whom. Like some of our respondents, they knew that ethnic labels concealed as much as they revealed, and they could push the boundaries of these labels without generally causing offence. It was this knowing-ness about how to get along with diversity that came through in our workshop and which we explored in our various research contexts.

Drawing around your hands might seem playful, but it opens up a whole series of questions about the micro-geographies of multiculture.

Dr Katy Bennett is an Associate Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Leicester, where she works on questions of social and cultural geography, especially identity, emotion, home, community and multiculture. Professor Giles Mohan is at the Open University and works on international development and migration. Together they were part of a team headed by Professor Sarah Neal called Living Multiculture. Out of this project the team has just published a new book called Lived Experiences of Multiculture: The New Social and Spatial Relations of Diversity, details of which can be found here.