Partition, 70 years on – the MMP’s annual lecture at the LSE, 22 November 2017

Tickets for Kishwar Desai’s MMP lecture on the Partition of India are still ‘on sale’ (don’t worry: they’re free – you can book here) on the LSE website. Following the attention given to this turbulent event in the press, on TV and film this year, it will be fascinating to hear how the newly opened Partition Museum in Amritsar, India, has fared – and how the subject is being treated in the Indian and Pakistani media.

Lady Kishwar Desai – the chair of the Arts And Cultural Heritage Trust, which has set up the world’s first Partition Museum at Town Hall, Amritsar, Punjab – will be giving the MMP annual lecture at the LSE on Wednesday 22 November, on the subject of ‘Partition, 70 years on: what have we learnt from the division of India?’

On the Partition Museum’s website, Santosh Bali, one of the people whose oral history is available to listen to, comments that the present generation doesn’t know how the independent states of India and Pakistan came into being or ‘how we got this freedom’. Now in her 80s, she clearly feels that it’s a good thing that these stories are finally coming to public attention, even though the memory of those times still brings tears to her eyes. And Santosh, by her own admission, got off relatively lightly from the whole experience – her family only lost, in her words, all their belongings.

The video is part of the Partition Museum’s oral history collection. Click here to watch the full collection © Partition Museum

But it’s a funny thing, this kind of switch between ignorance and knowledge. If the younger generation in India and Pakistan knows little about the birth pangs of their countries, it is partly because the older generation held back from telling them. There is nothing in this that is particular to the Indian/Pakistani story. Holocaust survivors often went decades before talking of their experience, just as people who had fought in either of the World Wars of the last century found it impossible to talk about their experiences before their final years. It’s a phenomenon well known to psychologists (often called the 50-year rule) and brilliantly evoked in Richard Flanagan’s 2013 novel The Narrow Road to the Deep North:

Immediately after the war it was quickly like the war had never been, only occasionally rising up like a bad bump in the mattress in the middle of the night and bringing him to an unpleasant consciousness. [. . . ] Sometimes, it was hard to believe he had ever really been to war at all.

There came good years, grandchildren, then the slow decline, and the war came to him more and more and the other ninety years of his life slowly dissolved. In the end he thought and spoke of little else – because, he came to think, little else had ever happened.

If the limited knowledge a younger generation has of the previous generation is in part down to the lack of curiosity of one generation and the reticence of the other, there is another kind of ignorance (in the original sense of ‘lack of knowledge’) in terms of the stories and records that find their way into the public domain. A generation grew up in post-war Germany in largely blissful ignorance of its country’s role in the Second World War because there was no mention of it in the books they studied at school, and their parents and older relatives didn’t talk about it. Likewise, generations of young Japanese students grew up in a country where the 1941–45 conflict was a conspicuous blank in all schoolbooks. Who’s at fault for their ignorance?

Thanks to the TV programmes, films and features there have been this year in the press and wider media, the events of Partition are now part of the public domain in the UK in a way that they arguably were not before. My first awareness of Partition, though, was reading Freedom at Midnight (by Larry Collins and Dominique Pierre) in my 20s, a book that mapped the trauma of the period while allowing a (relatively) young British man to retain his faith in the Brits as the good guys. I don’t think I could hold on to that faith now, when so many other historical records provide a picture of the British imperial ‘adventure’ that is the polar opposite of the one I imbibed at school. I feel embarrassed about my ‘ignorance’ now, just as the young generation of the 1960s and 70s in Germany felt embarrassed, and then angry, about their ‘ignorance’ of their country’s past. But I’m not sure I blame myself for my ignorance, and I find it useful to remember that now when I am tempted to criticise others for their ‘ignorant’ views.

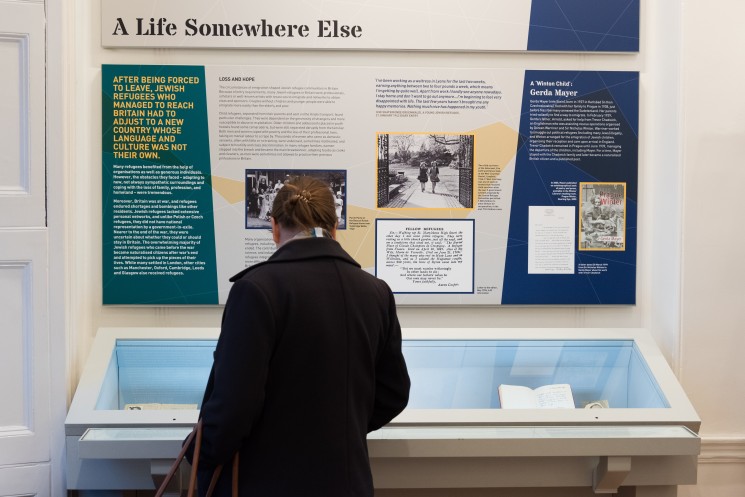

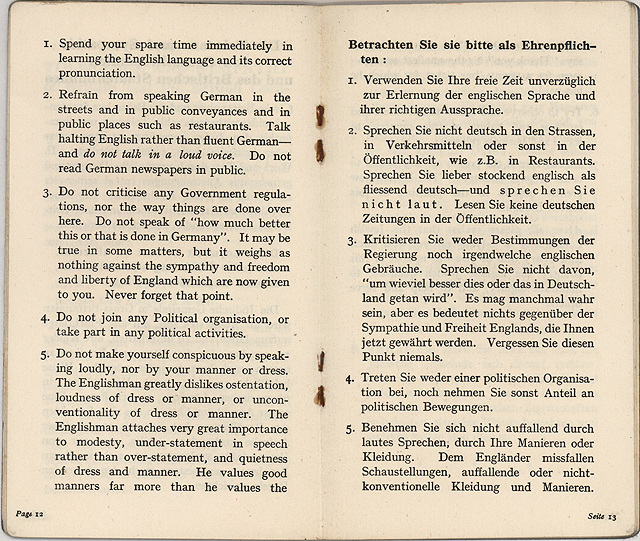

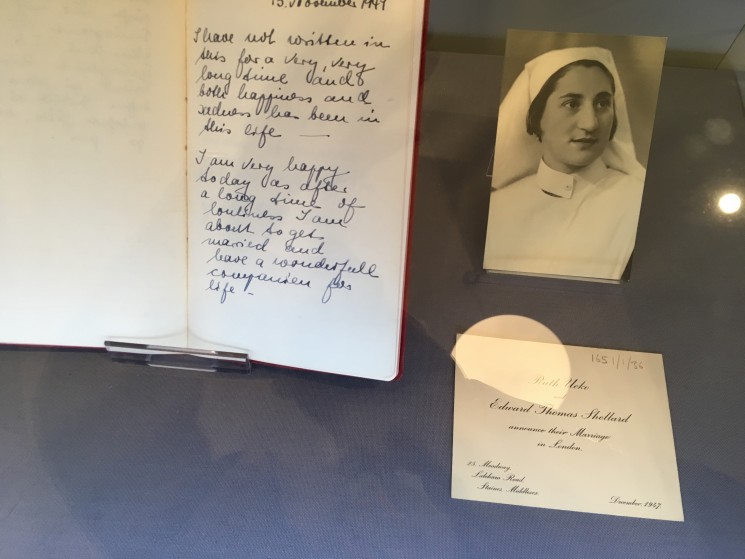

Knowledge is a burdensome thing but it is surely better than ignorance, and it can only be a good thing that the Partition Museum is shining its light on a period in the history of the Indian sub-continent that has for too long been shrouded in darkness. How important, too, if the 50-year rule mentioned above is true, for organisations such as the Partition Museum (and, in this country, the British Library and the Wiener Library, among others) to be gathering the oral testimony of a generation before it disappears.

Why not come along to the LSE on Wednesday 22 November and hear Lady Kishwar Desai reflect on the challenges of setting up this institution to collective remembering and on the differences it has made to the people involved, in one way or another, in the project?

Tickets for Kishwar Desai’s lecture, Partition, 70 years on: what have we learnt from the division of India?, are currently on sale. LSE students and staff are able to collect one ticket per person from the SU shop, located at Lincoln Chambers, 2–4 Portsmouth Street. Members of the public can ‘purchase’ tickets online via the event page on LSE’s website.

For more information and to book tickets, visit the event page on LSE’s website.