13 December, 2017

The past is not only a different country; it’s a contested one, too, and nowhere more so than in the extent to which Britain may or may not have been a ‘multi-racial’ society in earlier centuries. As with all debates of this kind, positions quickly become polarised and evidence exaggerated, with each end of the spectrum over-emphasising the historical record to suit its purpose. An example of this phenomenon was witnessed earlier this year, when a BBC cartoon aimed at school children attracted controversy. Hella Eckardt, an academic at the University of Reading whose work was quoted in the ensuing debate, reflects in this blog on both the evidence for a multi-racial Roman presence in this country and the best way of discussing it.

In August 2017, an educational BBC cartoon depicting the story of the son of a black commanding officer on Hadrian’s Wall caused controversy on social media.

A screen shot of the BBC’s “Life in Roman Britain”, with Quintus (right), the son of a Roman commander helping to build Hadrian’s Wall.

The alt-right commentator Paul Joseph Watson attacked the cartoon as a symbol of ‘political correctness’ and ‘rewriting history’, but multiple commentators then pointed out that there is a range of evidence for North Africans in Roman Britain.

The debate widened to consider ethnic diversity in the Roman Empire, and the question of how ‘typical’ long-distance migrants may have been in a province such as Britain. In classic Twitter and infowar style, much of the debate was vitriolic and toxic, clearly indicating that for some commentators the issue was about contemporary political concerns rather than ‘historical truth’. The Cambridge classicist Professor Mary Beard, in particular, wrote a very measured piece about the highly personal and aggressive abuse she received for making the academic case for ethnic diversity.

Reflecting on the controversy a few months on, and writing as one of the academics whose work was cited in the debate, I think it is important to move forward with reasoned debate and informed discussion, rather than aggressive and extreme polemic. It seems to me that there are two main issues: one is about the nature of the historical and archaeological evidence and the other about our ability to communicate these findings, especially when dealing with topics, such as migration or ‘race’, that are politically highly charged.

On the first point it is absolutely incontrovertible that the Roman Empire was characterised by relatively high levels of mobility, and that even in a marginal province such as Britain there would have been contact and interactions between Iron Age communities (themselves of course not uniform) and people from continental Europe, as well as North Africa or the Near East.

The drivers for movement included the Roman army and administration, but also trade and even tourism; in all these cases it would often have been high-status individuals who moved. The flip side of the coin is that the Roman Empire was obviously not a multi-cultural utopia, and conquered populations and slaves were moved against their will.

For Hadrian’s Wall, the place featured in the BBC cartoon, the historical (e.g. accounts of the emperor Septimius Severus, himself from modern Libya, meeting an ‘Ethiopian’) and epigraphic evidence (e.g. inscriptions mentioning officers or units) for an African presence have long been known. More recently, new scientific techniques have added important new information. Isotope analysis examines the chemical signatures preserved in teeth, which essentially reflect the water and food that a person consumed in childhood. The technique is better at excluding local origin than pinpointing specific origins; among the non-locals we can normally only say broadly that an individual came from somewhere cooler or warmer.

The project I led at the University of Reading identified a number of late Roman individuals in Scorton, York and Winchester who appear to originate from cooler areas, such as Germany or Poland, which makes sense, because we know that mercenaries from those areas served in the Roman army.

Another technique measures various aspects of ancient skulls, to establish African or Caucasian ancestry. For example, a 4th-century skeleton from York was identified as the remains of a woman aged 18–23 years, buried with rich grave goods that included both locally available (jet) and exotic (ivory) bracelets as well as an array of other impressive grave goods. Her facial characteristics suggest that she had a mixture of traits common in European (‘white’) and African (‘black’) populations but the results of the isotope analysis are ambiguous – she does not appear to have grown up in North Africa, so may be a second-generation migrant.

Finally, there is DNA analysis, as in the case of the so-called ‘headless Romans’ from York. These were discovered in an unusual cemetery of mainly male individuals, many of whom had been beheaded and some of whom bear injuries from combat. Genome analysis demonstrated that, while most appear to be of broadly ‘British’ descent, one individual may be from the Middle East; he also has an unusual isotope signature.

Reconstruction of the ‘Ivory Bangle Lady’ © Aaron Watson & University of Reading.

All archaeological data have to be interpreted, and it can be difficult to convey the complexities of the material in broad-brush summaries. It is also almost impossible to quantify numbers of incomers – especially given that scientific analysis has so far largely focused on unusual burials, thus potentially skewing the impression we form. While many of the right-wing commentators are focusing on ‘race’ in terms of skin colour, in the Roman world ethnicity was viewed quite differently: factors such as language (did the individual speak Latin or Greek well?), education, wealth, kinship and place of origin were probably more important. Archaeology and the reconstructions of the past we create are characterised by uncertainties, but conveying those complexities adds to our interpretation and allows us to challenge our own preconceptions. It is especially important that school children, who in Britain cover ‘the Romans’ at Key Stage 2, learn that the Roman Empire was not homogenous, but characterised by the interplay of locals and newcomers in wonderfully complex ways.

To convey these latest scientific findings, I have worked with the Runnymede Trust to create a website and learning resource for Key Stage 2 and the Ivory Bangle Lady also features in a new website about the history of migration in Britain aimed at older pupils.

Educational website on Romano-British diversity (http://www.romansrevealed.com/).

In conclusion, while contemporary concerns will inevitably shape what questions we ask of the past, it is clearly wrong to expect straightforward validation for current political points from archaeological evidence. What archaeology can do is to provide an increasingly rich and complicated picture of life, which we as a society can compare and contrast with other societies and different time periods.

Hella Eckardt teaches provincial Roman archaeology and material culture studies at the University of Reading. Her research focuses on theoretical approaches to the material culture of the north-western provinces, and she is particularly interested in the relationship between the consumption of Roman objects and the expression of social and cultural identities.

22 February, 2017

Waiting for the midnight hour

This year marks the 70th anniversary of Indian Independence. On 15 August 1947, ‘At the stroke of the midnight hour,’ as India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, sonorously proclaimed, ‘when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom.’ And so it did, but it awoke too to the realisation that its borders had been redrawn, that the state of Punjab in the west and Bengal in the east had been divided in two, and a new country, Pakistan, created to accommodate a predominantly Muslim population.

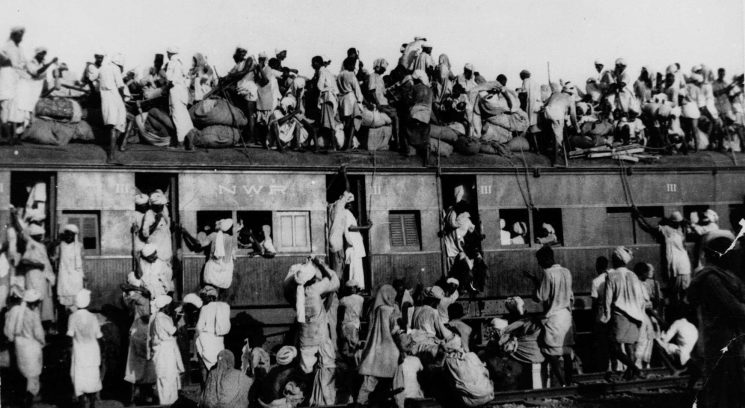

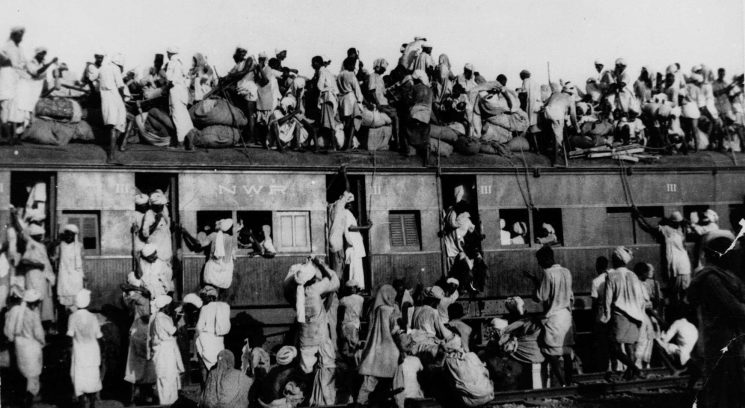

Indian Independence has therefore always been synonymous with the partition of India, with which it coincided almost exactly. The new boundaries of Punjab and Bengal were formally announced only the day before Independence, so that millions of households in those two states woke up to find themselves living in a country that no longer aligned with their religion: Muslims in the southern half of the states having to move north to a new home in Pakistan, Hindus and Sikhs in the northern half having to move south to India. There began what still stands as one of the largest migrations in history, with estimates of between 14 and 16 million people moving across the newly formed borders in the hope of finding sanctuary. Neither the newly created independent governments, nor the British administration in India under its last viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, were prepared or equipped to deal with the scale of this migration, or to contain the religious violence that duly ensued, so the independence of both countries was marked by bloodshed. How many people died in the weeks and months following partition is still unclear: the lowest estimate, given out by the British administration (which had previously pledged there would be no violence), is 200,000 deaths; the highest estimate is 2 million.

Easy to see why ‘celebrating’ this anniversary is particularly problematic.

Easy to see, too, why teaching it in schools – whether in this country or in India or Pakistan – has often appeared too challenging to take on. Families were riven in the process of partition, and many continue to maintain a cloak of silence over the events; where there is discussion, there are so many contested narratives that it feels impossible to present it with sufficient historical detachment. For all these reasons, it’s not surprising that so little is known now about this period of Anglo-Indian-Pakistani history.

Muslim refugees clamber on top of a train leaving New Delhi for Pakistan in September 1947.

Drawing the line

There are signs, though, that this might be changing. Last Wednesday, 15 February 2017, the Runnymede Trust’s report into the Partition History Project (PHP) pilot school programme was presented in the House of Lords to a packed council chamber. The pilot had been delivered in the winter term of last year, a time of heightened sensitivity around the issues of migration as a result of the EU referendum and the US presidential elections. It was delivered in four schools in Luton and Hitchin, with markedly different student populations, all of which, however, even those with a significant proportion of students of Bengali or Pakistani heritage, knew very little about the events. The pilot combined history lessons delivered to key stage 2 and 3 students, and the showing of a play, Child of the Divide by Sudha Bhuchar, which told the story of partition through the experience of one child. The headline results of the report are staggering, with a 70 per cent increase in students’ understanding of the events and clear indications that the use of drama, as a way of exploring an historical event through the prism of one family’s experience of it, had been hugely successful.

Perhaps understandably, teachers felt that teaching the story of partition in two lessons was asking a bit much, and the results of the PHP seem to bear this out. Although students retained a considerable amount of information, there was also some confusion about the circumstances leading up to partition, the identity of the key players in the events, the scale of the displacement that resulted and the nature of the religious groups affected. Two clear messages emerged: first, that teaching the history of partition effectively has to be undertaken in the context of British rule in India and in a broader discussion of Empire; and, second, that the subject of partition has particularly rich potential for a discussion of some of the issues of the day, including community cohesion, migration, religious pluralism and the legacy of Empire. Often these issues are confronted more comfortably through the prism of an event at some historical distance from the present.

The panel prepares to debate in Committee Room 2, House of Lords, Wednesday 15 February 2017. The panel, chaired by Rita Chakrabarti, included Professor Sarah Ansari (Royal Holloway, University of London), Lord Meghnad Desai, Lady Kishwar Desai (Partition Museum), Farah Elahi (The Runnymede Trust), the Reverend Canon Edward Probert (Salisbury Cathedral) and Canon Michael Roden. © Runnymede Trust

Lady Desai, who will be delivering the Migration Museum Project’s annual lecture later this year on partition, spoke from the panel with passion and interest about the process of establishing the first Partition Museum, which is due to open in autumn this year in Amristar. What is clear is that, although there are many who would still prefer partition to go undocumented or certainly uncommemorated, there are even more people who recognise this as their story and who are clamouring to be involved in it.

That same sense emerged from the response of the meeting to the panel’s discussion. Time and again people spoke about how their parents or their grandparents were only now beginning to talk about these events, having maintained a silence for the best part of 60 years, making them – the children and grandchildren of partition – viscerally aware of the division that it had caused in their families and extended families. The worry is, people who lived through these events are now in their 80s and 90s themselves: are we going to be able to capture their first-person records before (morbid thought) they leave us?

But there were a significant number of positives about the project, the report and the meeting, too. It was heartening to hear about the creation of an institution unafraid to commemorate such a complicated period of its country’s history. It was good, too, to feel that in this country there was an appetite for confronting historically contested narratives and encouraging some dialogue around them. It was reassuring, from the selfish perspective of the Migration Museum Project itself, to see how successful the use of drama had been in the pilot’s delivery, since we have long maintained that the human stories of migration have a weight and a pull that ‘objective’ accounts get nowhere near. And it was good, too, at a time when it occasionally feels that people are retreating into themselves and putting up the shutters, to feel that so many people were hungry to discuss these difficult matters and to throw open the curtains and let the light in on what had previously been kept under wraps.

The Runnymede Trust is an independent charity ‘working to build a Britain in which all citizens and communities feel valued, enjoy equal opportunities, lead fulfilling lives, and share a common sense of belonging’. The report mentioned in this blog may be downloaded here; anyone interested in finding out more about the report or about Runnymede is welcome to write to Farah Elahi, research and policy analyst at Runnymede.