Economic migrants or refugees? A core issue at the heart of migration past and present

The Migration Museum Project is blessed with a large team of fantastic volunteers, without whom we would find it hard to function and impossible to run our events and exhibitions. Assunta Nicolini is one such volunteer, and her discussions with visitors to our current exhibition, No Turning Back, have got her thinking about a number of issues that she feels are raised by the display. This blog is the result of her thoughts and discussions around two of the seven moments of the exhibition: the arrival in this country of Huguenot refugees after 1685, and the passing of the Aliens Act in 1905.

No Turning Back: Seven migration moments that changed Britain introduces visitors to powerful artworks and archive images carefully interwoven to create a narrative that brings together past and present. It is within history that we so often find the key to understanding many of the social realities we inhabit today.

Migration is no exception. One of the seven moments shown in the exhibition, the year 1685, holds a particular relevance in the understanding of today’s migration dynamics.It was the year that France made Protestantism illegal, precipitating the arrival in Britain of about 50,000 French Protestant Huguenots. Centuries before the drafting of the Refugee Convention (1951), and with no legal framework in place establishing roles and responsibilities towards people escaping persecution, the term ‘refugee’ was introduced into the English language through the French Huguenots arriving on British soil in search of protection (refuge). It took about three centuries, a series of major humanitarian crises and, ultimately, the horror of the Holocaust for the international community to establish a legal framework aimed at giving protection to people fleeing persecution.

Article 1 of the United Nations’ 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.

The history of the Huguenots in Britain is not, however, just about one of the largest refugee groups to seek safety and protection in this country. Their life experiences were not simply defined by their ‘refugee-ness’; on the contrary, their arrival and settlement offer just as important insights into the realities of migration.

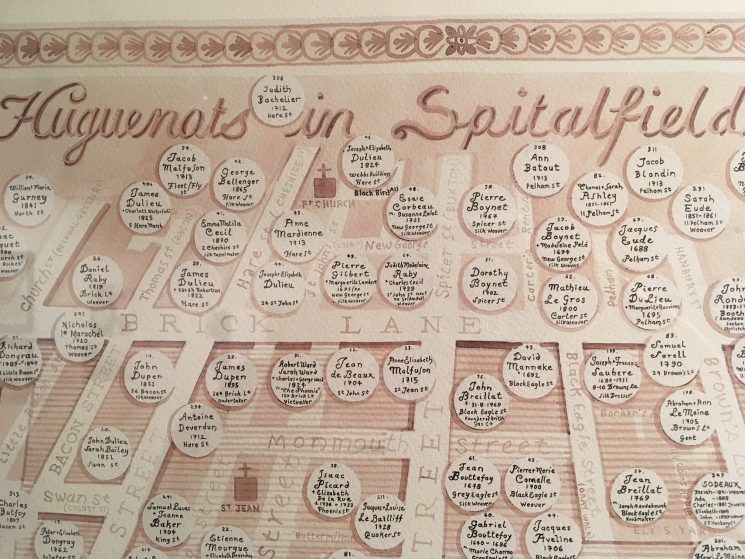

In the exhibition, Adam Dant’s delightful map representing this historical moment takes the curious eye of the visitor through a detailed drawing of the streets surrounding East London’s Spitalfields Market. Surnames of French origin are circled to indicate where the Huguenots were to be found. As visitors adjust their eye to these several locations, they then notice a further, more crucial detail. Surnames are accompanied by ‘professions’, mainly artisanal, such as weavers, clockmakers and silk merchants.

A detail from Adam Dant’s ‘Huguenots in Spitalfields’. A range of professions are readable in these circles, for example: ‘silk weaver’, ‘undertaker’, ‘victuailler’, ‘reed maker’ and ‘gent’. © Adam Dant

Such detail is crucial as it allows the visitor to expand their understanding of who these people were, beyond the one-dimensionality of their ‘refugee-ness’. Being given protection in Britain was not the end of the Huguenots’ ‘migration journey’ – settling and restarting their lives, as well as providing for their families, was just as important. Historical archives tell us that, although the Huguenots left France clandestinely and at short notice, taking little with them and with limited time for planning ahead, they were nevertheless aware that certain destinations were better than others. London, for example, offered not only protection but also great opportunities for employment and hence a better place to settle.

You don’t need to be an expert to spot the striking similarities with contemporary experiences of migration. Today’s refugees are no different from those of centuries ago – like them, they are human beings who, in order to have a life beyond survival, need to work. Obvious though this point is, the current obsession in the media and parliament is the apparent distinction between ‘refugee’ and ‘economic migrant’.

It is possible, however, to make such complexity simple, and to offer an accessible understanding of such migration dynamics. Migration experts have been drawing attention to the fact that immigration statuses – the classification of refugee, migrant or asylum seeker, for example – are never fixed but on the contrary are dynamic and mobile.1 Rigid legal categories labelling individuals either as migrants or refugees have become increasingly obsolete, as they fail to reflect the personal and global realities of contemporary migration.2 The stories of refugee-migrants themselves consistently show that people might start their journey as refugees but, like the Huguenots, become economic migrants later on. Scholars have widely recognised that contemporary migration is defined by its mixed nature and by continuity, rather than an opposition between forced and voluntary migration (see this video for Dr Nicholas van Hear’s clear outline of this matter).

The overlapping and mobility between immigration statuses is an aspect that was overlooked at the the time the Refugee Convention was drafted. Understandably, soon after the Second World War, the concern of the international community was focused predominantly on making sure that persecuted people would be protected outside their home countries. Economic migrants, on the other hand, could not benefit from a specific legal framework protecting their rights, since the ‘voluntary’ dimension of their migration implied they took responsibility for their own protection.

In recent decades, however, a greater emphasis has been placed on additional legal frameworks aimed at correcting the shortcomings of the Refugee Convention, in particular those based on International Human Rights law. A rights-based approach can in fact not only provide a framework for the protection of economic migrants but also enhance refugees’ protection, while at the same time establishing the universal human right to seek asylum.

Despite the availability of different legal frameworks governing migration and ‘refugee-ness’ today, there is no agreed position in policy making, advocacy and public opinion. Public opinion is characterised by narratives of ‘good and bad’ refugee-migrants, of ‘deserving and undeserving protection’, and of ‘inclusion and exclusion’. Refugees are mostly perceived as victims, but the moment they display willingness to economically improve their lives they are automatically seen as economic migrants and hence as undeserving of protection and support.

Satire on the Aliens Act – drawing of Britannia turning away a group of refugees who have just disembarked at a port, 1906. Part of the Migration Museum Project’s ‘No Turning Back’ exhibition. Image courtesy of the Jewish Museum.

Far from being new, this narrative partly finds its roots in another pivotal migration moment shown in the exhibition – 1905, when the Aliens Act was passed in Britain, the first legal framework regulating migration and based on the notion of ‘desirable’ and ‘undesirable’ immigrants. The Aliens Act was the result of rising nationalism based on disproportionate fear about newly arrived refugees, mainly Jews, and migrants of Asian origins. A satirical drawing from the time, showing Britannia saying ‘I can no longer offer shelter to fugitives; England is not a free country’, aptly describes the feeling of rejection felt by Jewish refugees. Another pamphlet from the archives directs the visitor’s attention to the fact that rejection was felt not only by refugees but also by immigrants, with trade unions attempting to dismantle the unfounded belief that migrants were competitors in the job market and bad for the British economy. Through the various details of this migration moment, the visitor is also encouraged to think about the importance of keeping labour migration channels open to refugees today.

History reminds us that looking at migration through rigid binaries of ‘desirable’ and ‘undesirable’, ‘deserving’ and ‘economic’, risks reinforcing a dangerous divide that often underpins much of public opinion and policy making. What we witness today and the stories that migrants and refugees tell us bear a profound resemblance to the past and urge us to consider that a refugee-migrant should not be seen as a threat but rather as an asset to Britain and host countries in general.

1 See, for example, Schuster, L (2005) ‘The Continuing Mobility of Migrants in Italy: Shifting between Statuses and Places’. Oxford: COMPAS and Bloch (2011)

2 Zetter, R (2007) ‘More labels, fewer refugees: remaking the refugee label in an era of globalisation’, Journal of Refugee Studies, Volume 20, Issue 2, 1 June 2007, 172–192, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fem011