A new brochure and a cloud’s silver lining

We’re putting the finishing touches to our new brochure (our sixth, by my reckoning), which we hope to have ready in paper form and as a pdf on our website in the next few weeks. It’s always an interesting process: taking stock of how far we have travelled and how much we have done, re-examining some of the arguments we put forward in support of our cause previously, seeing how much our current aims coincide with those with which we started five years ago. It’s incredibly humbling, too, to see how much what we have achieved has depended on the partnerships and unsung contribution of volunteers, linked organisations, supporters both individual and corporate.

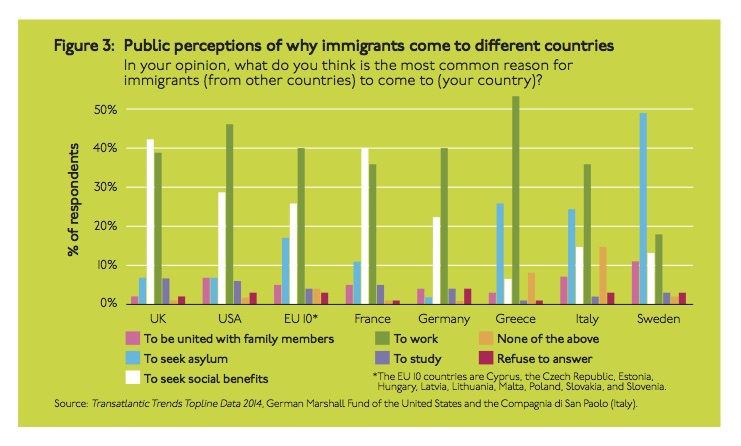

One of the largest chapters in the brochure sets out the case for a migration museum, building on the latest research and reflecting a changing climate in the country’s attitude to migration. Much of the evidence here surprises me every time we revisit it for a new edition of the brochure – the facts, for example, that the UK, statistically, is more cynical about the reasons immigrants come to our country (more than 40 per cent of those surveyed saying they do so to seek benefits) than all other European nations, or that there is a greater divide in our country than all others between those who are young and degree-educated and those who are older and not university-educated in terms of people’s opinion of the impact of immigration on the economy. And then there is the statistic that in some ways lies at the heart of what the Migration Museum Project has been about from the word go: the fact that more than three-quarters of the population see immigration a ‘problem’ nationally, but less than one third see it as a ‘problem’ in their local area.

One of the tables used in our forthcoming brochure; this shows the UK public to be more likely than that of any other country surveyed to think that immigrants come to this country to seek social benefits © Transatlantic Trends

This kind of mismatch is not unusual: the misrepresentation of the level of crime, for example, is often used as evidence that the fear of crime dramatically outstrips the reality. But it is nevertheless an interesting illustration of our ability to hold an intellectual or abstract opinion that is at variance with the day-to-day reality of our lives. Making exceptions for people we know and like seems to be part of the basic human condition:

‘I hate all Man City supporters.’

‘But Tim, your best friend, supports City.’

‘Yeah, but Tim’s different.’

or

‘All people from eastern Europe should go “home” now.’

‘What, including Pavel, our Julie’s boyfriend?’

‘Well no, obviously not Pavel. Of course, he can stay.’

It’s not quite the same, but there was an interesting illustration of this basic point – that people feel differently about ‘others’ once they are actually connected to them, through their stories, through meeting them, through living among them – in the BBC three-part programme that earlier this year ‘commemorated’ the 25th anniversary of the murder of Stephen Lawrence. In the first episode of the rather optimistically titled Stephen: The Murder that Changed a Nation, there is a moment (around 48 minutes in) when Doreen and Neville Lawrence become aware of an article about them in the Daily Mail (Monday 10 May 1993), criticising them for associating themselves with a march that had ended in violence (the article’s sub-heading read ‘Activists turn brutal killing of a schoolboy into a political cause.’). The Lawrences and their advisers consider how they should respond, and somebody suggests a phone call to the paper. As they discuss options, Neville Lawrence mentions that he knows someone senior on the paper, having done some plastering work on his new home. This someone senior turns out to be the newspaper’s editor, Paul Dacre, whose telephone number Neville has.

He phones Dacre.

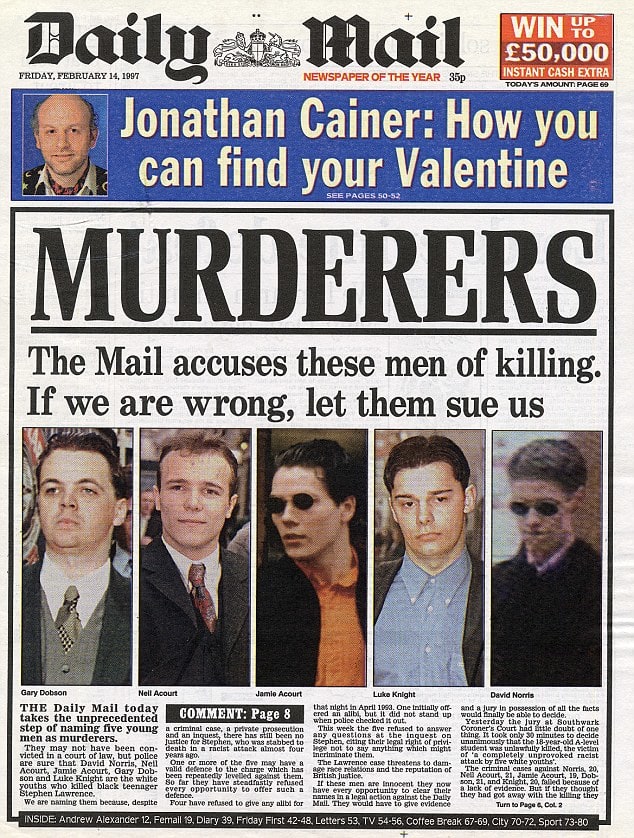

What followed is quite extraordinary. Dacre, who hadn’t realised that Stephen Lawrence was Neville’s son, apologises for the article, arranges a corrective interview that is published days later in his paper and then – four years later, in 1997 – is personally responsible for the Daily Mail’s historic and sensational front page article that names the ‘Murderers’ of Stephen Lawrence and challenges them to sue the paper if they think they have been falsely accused. It was an article that shocked people, both because it dared to say what no other paper to that point had, and because the Mail was the paper that many people would have considered the least likely to run such a story. In one broad stroke, it managed to subvert liberals’ opinions of the Daily Mail while possibly also confounding the expectations of its readers.

The famous front page of the Daily Mail on 14 February 1997, an exact print replica of Paul Dacre’s handwritten layout.

Of course, the story doesn’t have the resolution that we might all have hoped for. Only two of the ‘murderers’ have ever been convicted, and the chances of the others being brought to justice seem increasingly slim. More significantly, of course, there’s no getting over the fact of Stephen Lawrence’s murder. With damning poignancy, Doreen Lawrence talks in the BBC programme of the family’s decision to bury Stephen in Jamaica, ‘because England did not deserve him’. Despite the title of the BBC programme, has the nation in fact changed to the extent that she might have made a different decision now? Huge question marks remain, but it is nonetheless gently reassuring to think that a paper that is regularly pilloried for promoting what people see as a right-wing, xenophobic agenda in this instance so firmly aligned itself in opposition to an act of racist brutality, largely on the basis of the human contact between its editor and the victim’s father. Candidly, in the BBC’s programme, Dacre wondered whether he would have written the piece had he not known Neville Lawrence personally – and ended up deciding that he would not have.

‘Any fool can know,’ as Albert Einstein said. ‘The point is to understand.’