Hold the Line – retracing a 90-year-old journey

The route from south-east Europe to north-west Europe is one taken by thousands of people seeking asylum and refuge from war and persecution. Newspapers constantly present this as a contemporary challenge, but, as this blog illustrates, this is a well-trodden path – for the artist Freya Gabie this route is the basis of a project she hopes will last for several years.

Freya Gabie has just completed an 11-day journey, retracing the footsteps of Pavel Kiprionavitch Kastorny, who, ninety years earlier, in 1929, travelled from Bulgaria to Saint-Louis, France, the last place he is known to have visited but where he is assumed to have started a new life. We’ll come to why she’s done this in a while.

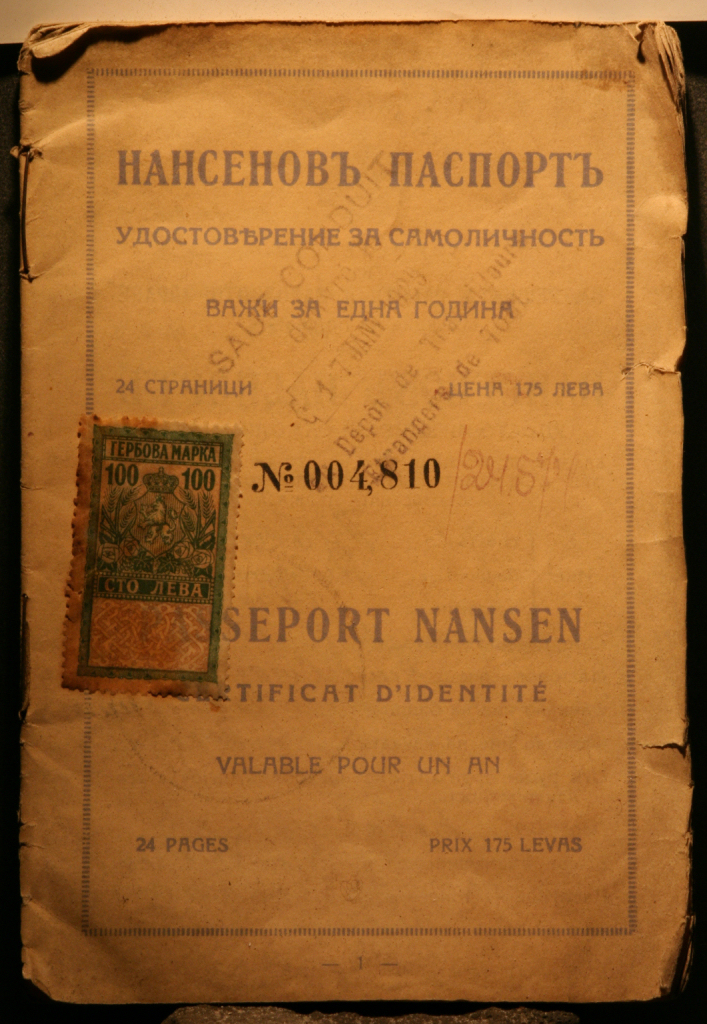

Little is known about Pavel Kiprionavitch Kastorny, except that he was a Russian refugee and that he was able to travel across Europe by virtue of his Nansen passport. And it’s safe to say, paraphrasing Sir Michael Caine, that not many people know about the Nansen passports either.

First, a bit of background.

We live in turbulent times, but it can be reassuring to compare them with previous periods when the world seemed even more chaotic than it does today. By the time the First World War had come to its grisly end, four empires had been destroyed: the German, Ottoman, Russian and Austro-Hungarian. The Russian revolution led to the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people, seeking refuge elsewhere, and whom Lenin then stripped of their Russian nationality; the establishment of new countries in the wake of the demise of the four empires led to further displacement, as did war between Turkey and Greece and the plight of the Armenian population. Estimates of displaced people are hard to come by, but the number of Russian refugees alone is put at 800,000, so the total figure is clearly going to be in the millions.

Many of these displaced people were soldiers, and it wasn’t until four years after the war, in 1922, that the last German and Austro-Hungarian soldiers who had been in Russian captivity, and the last Russian soldiers who had been prisoners of war in Germany were exchanged – 400,000 in total. The credit for this exchange was given mainly to the Norwegian Fridtjof Nansen.

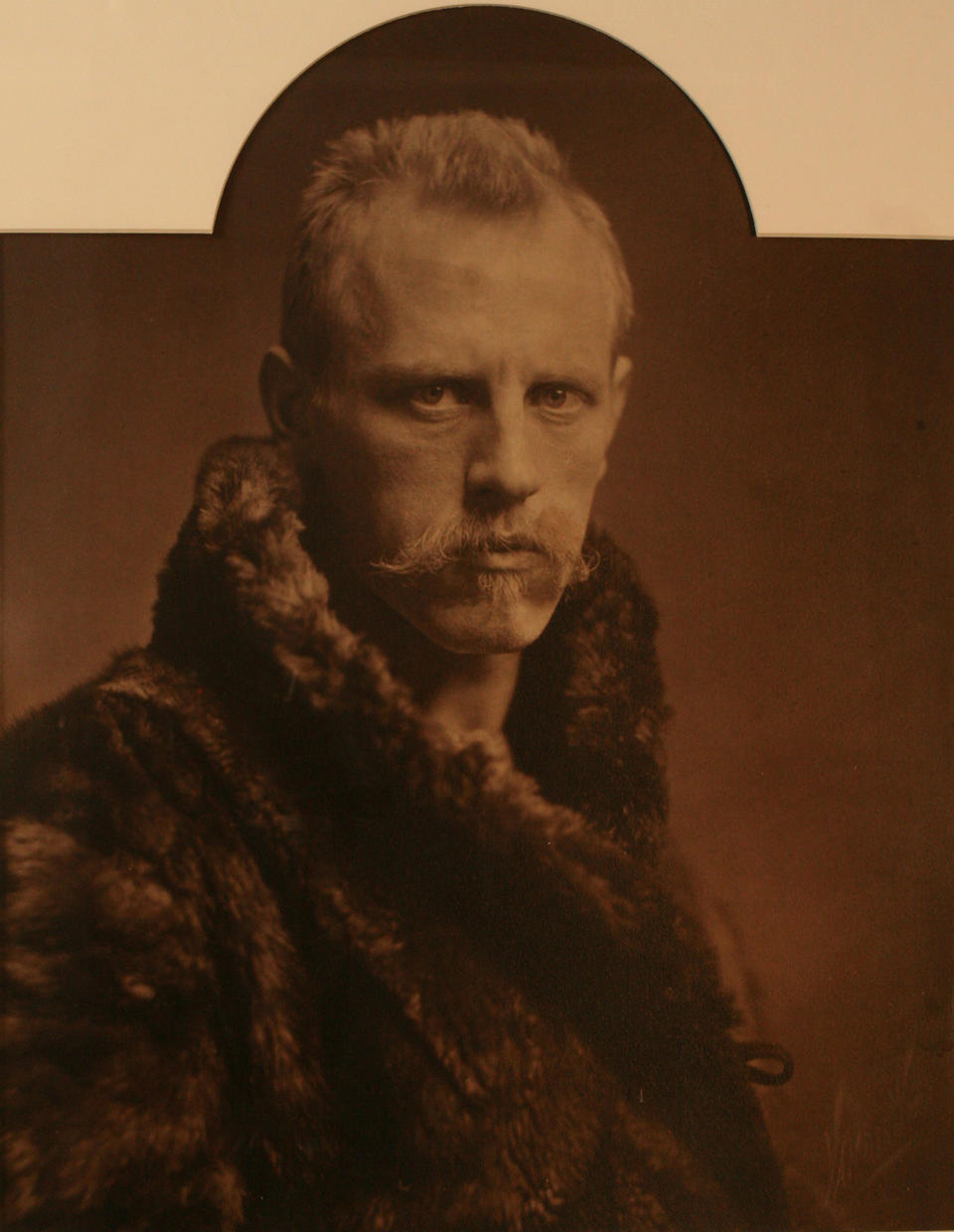

Fridtjof Nansen (1861–1930) in his polar expeditionary days. After an early life of sporting activity and polar exploration, he turned to scientific research, diplomacy and humanitarian work. The last post he held was the League of Nations’ High Commissioner for Refugees. © Fridtjof Nansen Institute

The Norwegians are justifiably proud of Fridtjof Nansen (1861–1930). A champion skier and skater in his youth, he went on to become a polar explorer of international repute before becoming a scientist, diplomat and humanitarian, and the winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. As the League of Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, he convened an intergovernmental conference on refugees in 1922, which led to the introduction of the Nansen passport, a passport that allowed the bearer to cross borders legitimately and which was recognised by 52 countries (and continued to be recognised until the end of the 1930s). According to the Fram Museum (devoted to a ship Nansen built for one of his Arctic expeditions), “Many consider Fridtjof Nansen to be one of the greatest men Norway has ever nurtured”; and his biographer said of him that “[he] is among the few really worthy winners of the Peace Prize”.

Around 450,000 Nansen passports were distributed to displaced people, and the artist Freya Gabie has now identified – and, in the case of Pavel Kiprionavitch Kastorny, retraced – more than 70 of the journeys taken by these people. Her plan is to travel one of these journeys every year for the foreseeable future, following the same route and the same timescale, seeing how the project grows and who joins her.

The Nansen passport used by Pavel Kiprionavitch Kastorny, a Russian refugee who travelled on this passport from Bulgaria to Saint-Louis, France, in 1929. Famous holders of Nansen passports include Robert Capa, Marc Chagall, Vladimir Nabokov, Sergei Rachmaninov and Igor Stravinsky. © Fridtjof Nansen Institute

Freya first came across the Nansen passport in 2016, while spending three months as the artist in residence at USF Verftet in Bergen, Norway. Fascinated by what she discovered, and by the resonance with today’s displaced populations, she began to formulate the project, partly inspired by a marine research expedition she went on aboard the boat Dr Fridtjof Nansen*. Freya explains her interest here:

This idea of connection to places, how one relates and moves between them was an important aspect of the voyage for me – both in the context of my research, the individual historical journeys that I’d traced with the Nansen Passports but also the hundreds of thousands of people today making (or attempting to make) similar journeys for similar reasons.

As Pavel Kiprianovitch Kastorny did ninety years ago, Freya started her journey in Bulgaria. At the time of writing, she has just completed her journey in Saint-Louis. You can follow her journey on her website, where you will also be able to see a map of her journey (created with the help of Michael Horswell from the geography department of the University of West England, Bristol) and the photographs she has been posting as part of her project. We hope that she will be soon posting a blog for us, too, once she is back in the UK.

Freya Gabie’s drawings of stones, collected on her journey across Europe: ‘Throughout the project I have been drawing and replacing the tiny stones I have passed on my path. I like the fact that these small, insignificant pieces of the landscape are free to move across the landmass of Europe, absently kicked along and across borders. Each stone has been given two portraits: one drawing has been sent to people and places across the world connected to the project and the other gathered into an accumulating record of the journey. I have drawn more than a hundred of these stones and hope to exhibit the collection as a legacy to the project.’ © Freya Gabie

This route, from Bulgaria northwest across Europe, is the same that many displaced people today are making from the war-torn countries of the Middle East, a further reason for Freya’s selecting it. For those current displaced people, sadly, there is no Nansen passport to ease them across borders and make their journeys fractionally safer.

*As a measure of the esteem in which Nansen is held, the Fridtjof Nansen Institute – an independent foundation engaged in research on international environmental, energy and resource management politics and law – has an extensive research programme under seven main banners, and there is also the EAF Nansen Programme, which focuses on fishery research.

Freya Gabie studied sculpture at Chelsea College of Art and the RCA, and now works between Bristol and London. Her practice is site responsive: focusing on connection and exchange. She makes objects, drawings and interventions that respond to particular histories, stories and places. Hold the Line is the project described in this blog.

The Fram Museum, a museum based around the boat that Nansen built and which Otto Sverdrup and Roald Amundsen also used on their exhibition, is located in Oslo.

The Fridtjof Nansen Institute, an independent research foundation, is based in Polhøgda, the home of Fridtjof Nansen, in Lysaker, Norway.