What have EU nationals ever done for the UK’s heritage sector?

In this guest blog Olivia Bridge considers the contribution EU nationals have made to the museum sector, and what impact the UK’s withdrawal from the EU may have on the culture and heritage industries.

Artists and, more generally, people working in the culture and heritage industry have always been conspicuous for their mobility, travelling across borders to follow the best opportunities, the biggest influences, the wealthiest patrons. The UK has benefited from this creative traffic as much as any other country, with many of the fixtures of its artistic heritage turning out to have been born outside the country: George Frideric Handel, Walter Sickert, Lucien Freud and Frank Auerbach, to mention just a handful of artists and musicians, and Prince Albert, heavily responsible for some of the UK’s most famous museums (the Science Museum, Natural History Museum and the Victoria & Albert Museum). Ironically, both what constitutes the UK’s cultural heritage and also the means by which that heritage is communicated to the world at large are the responsibility in large measure of people born outside the UK.

George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) by Balthasar Denner c. 1726. Handel is considered one of the greatest composers of the Baroque period. Born in Germany, he lived in England for more than 50 years, taking on British nationality, and was influential in the development of the Royal Opera House in London; his philanthropy was also a significant factor in the creation of the Foundling Museum.

That connection continues to this day. Currently, 4.6 per cent of employees in UK art institutions are EU nationals – a figure that rises as high as 15 per cent in some of the larger museums. In the field of archaeology, Europeans represent the majority of the workforce on certain projects (nearly 60 per cent, according to the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists). Research suggests that this state of affairs is largely because there is too little homegrown talent to perform these roles: a report by the Education Policy Institute found that the proportion of students in the UK opting for an arts-based subject in 2017 dropped to its lowest level in a decade. Numbers of students studying archaeology have been in steady decline since 2008, forcing departments at universities in Birmingham, Bangor and Manchester to consider axing their courses altogether.

Archaeological dig in Derry, Londonderry. © Kenneth Allen – geograph.org.uk/p/3674363

Over the last few years, the contribution of EU nationals to the arts and heritage sector has been in steady retreat. The most recently published figures show net EU migration is at its lowest level in the past five years and, according to Bernard Donoghue, the director of the Association of Leading Visitor Attractions, the last six months have witnessed a ‘brain drain of skilled workers in the culture, science and design sectors’. Recruiters in these sectors are becoming concerned over their access to talent, citing as worrying signs the departure of a number of iconic artists, curators and museum directors with international reputations in anticipation of Brexit (both the Tate Modern’s chief curator, Sheena Wagstaff, and director, Chris Deacon, for example). Most famous among these, perhaps, is the previous director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Martin Roth (sadly, now deceased), who quoted the EU referendum as a ‘personal defeat’ before returning to Germany in 2016. Such concern is borne out by a report by Historic England, which estimated that the UK will over the next few years be short of between 25 per cent and 64 per cent of archaeologists desperately needed to carry out more than 40 major infrastructure projects such as High Speed 2 and Crossrail.

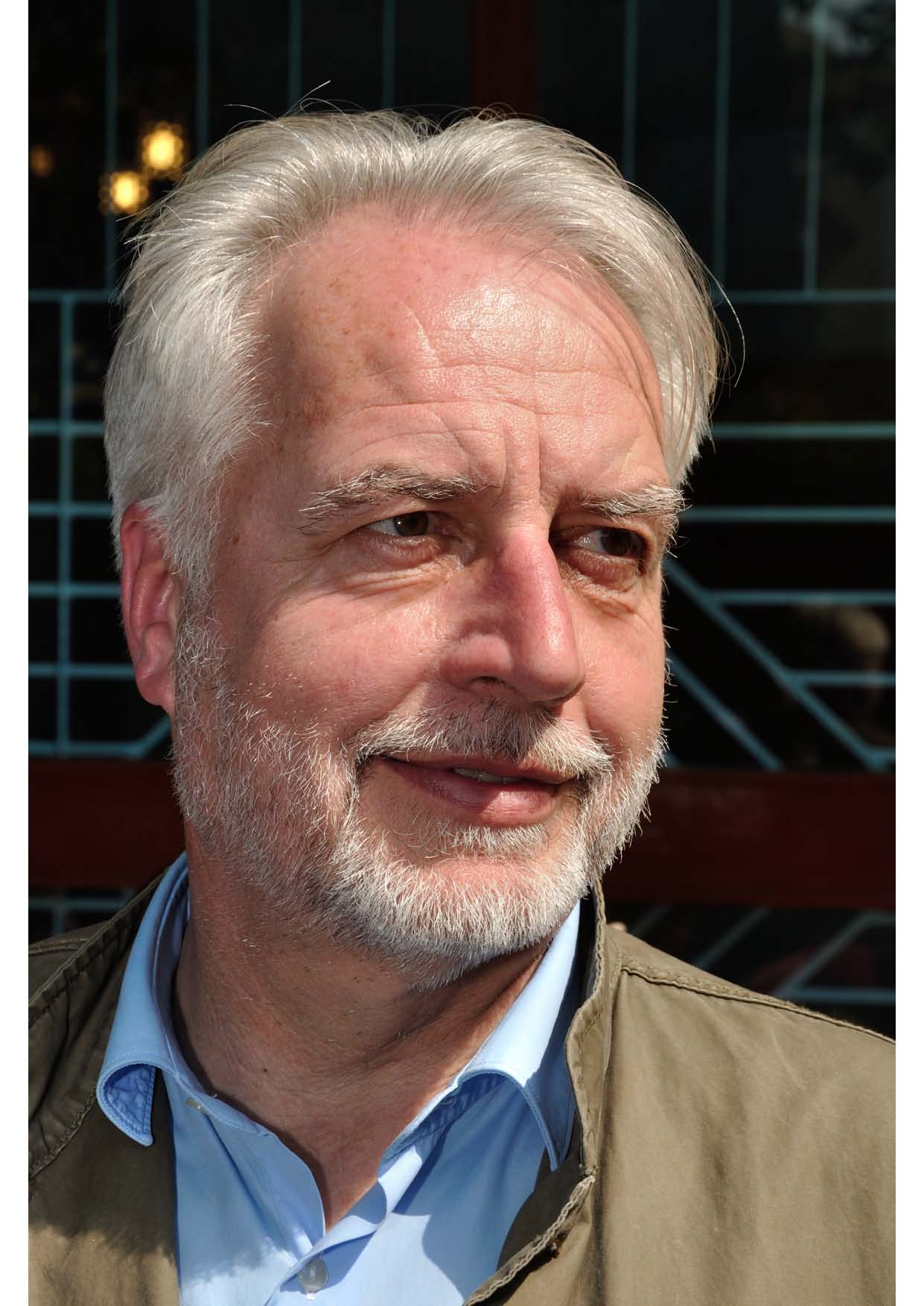

Martin Roth (1955–2017), previous director of the Victoria & Albert Museum and distinguished friend of the Migration Museum. This photograph was taken at a conference on ‘Strategic Transformations: Museums in 21st Century’ in Kolkata organised by the National Council of Science Museums, India in 2014. © Biswarup Ganguly

The uncertainty surrounding the future relationship of the UK’s arts and heritage sectors to the EU is likely to be of particular concern to the EU nationals already living and working in these sectors in the UK. It was some relief, therefore, when the UK government released its White Paper in July 2018; the document blueprinted the UK’s future relationship with the EU and laid out a UK–EU Culture and Education accord, significantly valuing the importance of a ‘continued mobility of talented individuals’ after Brexit and maintaining that ‘the UK will always be a European country that advocates cultural diversity as part of its global identity’. In line with these sentiments, non-British EU nationals currently living and working in the UK have been promised Settled Status if they apply for it before 2021, so for the time being the recruiters need not worry.

There are, however, legitimate concerns about the future. One is that the UK government has decided to apply the same immigration criteria to EU migrants as it currently does to all other migrants – despite warnings from many leading organisations such as the Confederation of British Industry (CBI). Under the government’s proposed Brexit deal, artists, museum technicians and guides, curators and archaeologists who seek to work in the UK will need to apply for a Tier 2 visa once the UK leaves the EU. This is likely to have a considerable impact on museums and heritage centres, but the ‘best and brightest’ might also find themselves entirely ineligible for this visa. As a basic requirement, Tier 2 visas are granted to workers who earn over £30,000 a year, which would rule out many EU artists, curators and archaeologists from a future career in the UK. To make things worse, there is a cap on the number of Tier 2 visas issued every year (the figure is currently 20,700), which means that priority is usually granted to the highest-earning workers, such as technology experts and business owners.

The potential prospect of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit in recent months has served to deter migrants – and recruiters – further. After Brexit, employers will need to apply for a Sponsor Licence if they want to hire from the EU. The CBI argues that sponsor licences will bury smaller institutions, which will struggle to meet the administrative and financial costs of this system, since ‘most businesses would not consider job applicants who would require a Tier 2 visa to work in the UK because of the prohibitively expensive and time-consuming process of being a licensed sponsor, applying for a visa and paying relevant fees and charges’.

The Seven Sisters in Sussex, often used as a stand-in for the White Cliffs of Dover – falling off the edge of them a scenario that few people are promoting in the run-up to 29 March 2019. Photo by DAVID ILIFF. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

The CBI report paints a bleak picture for the arts and culture industry, warning that, without major reforms to the visa system for EU citizens and some rapid development of homegrown talent, our museums will be unable to continue to benefit from the range of artistic expertise that has been their strength up to now. There are silver linings for the industry, though. One of them is – surprisingly – a devalued pound. The Office for National Statistics reveals that tourism to the UK has risen by 4 per cent since the EU referendum, bringing in more than 39 million visitors. A further plummet in the pound will likely drive this trend further, hiking up visitor numbers and arguably increasing local budgets for museums, attractions, heritage centres and exhibitions up and down the UK.

A further silver lining is that Creative Europe – the arts and culture industry’s funding lifeline – has extended its commitment to the UK until the end of 2020. And even in the event of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit (and immediate withdrawal from the funding scheme), the Home Office has in the White Paper assured the arts industry that the government will fill any holes in funding lost by Creative Europe.

Whether these turn out to be genuine silver linings or merely a clutching at straws will become apparent only in time. For the sake of the vibrancy of the UK’s arts and cultural sectors, internationally renowned and the envy of many other countries, it is to be hoped that the Holbeins, the Handels, the Freuds and the Roths of the future will continue to see the UK as the hotbed of artistic talent it has been for so many centuries.

Olivia Bridge is a content writer and political correspondent at immigration law firm Immigration Lawyers London.