22 January, 2018

If you find yourself anywhere near Croydon between now and April 2018, go and visit the Gujarati Yatra exhibition, which is nestled away in the Museum of Croydon and occupies the stairwell, corridor and café of the Clocktower building in which it is housed.1

This exhibition tells the story of the double diaspora of the Gujarati people, many of whom left the westernmost state of India in the 19th century to develop the trade and the industry of ports in the east and south of Africa, before being forced in the 1970s to leave their African homes and communities to find refuge in the UK and other countries. Anyone only partially familiar with the story of this population will find plenty of treasures in the exhibition, which is dominated by the oral and video testimonies of Gujaratis living in Croydon (host to one of the largest Gujarati communities in the country) and other parts of London and the UK, and by objects and artefacts loaned by ordinary people and by academics and historians. These oral histories and personal testimonies clearly shaped the narrative of the exhibition.

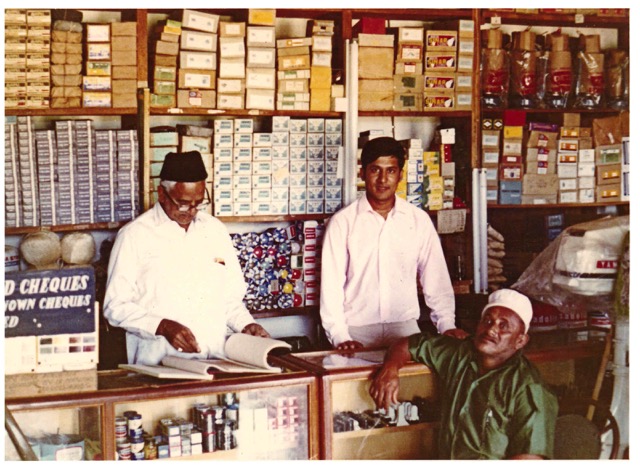

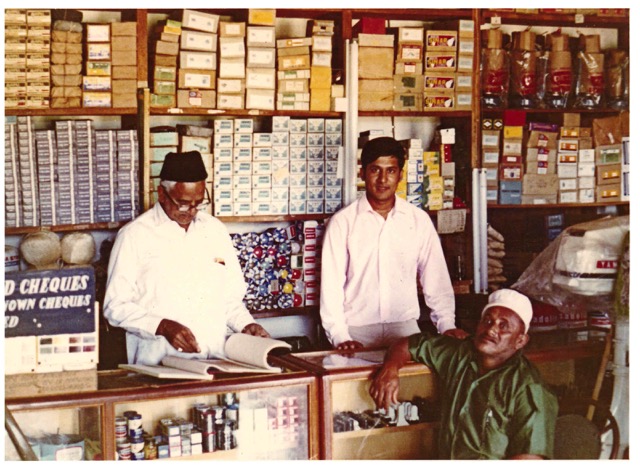

Dukawallah in Uganda.

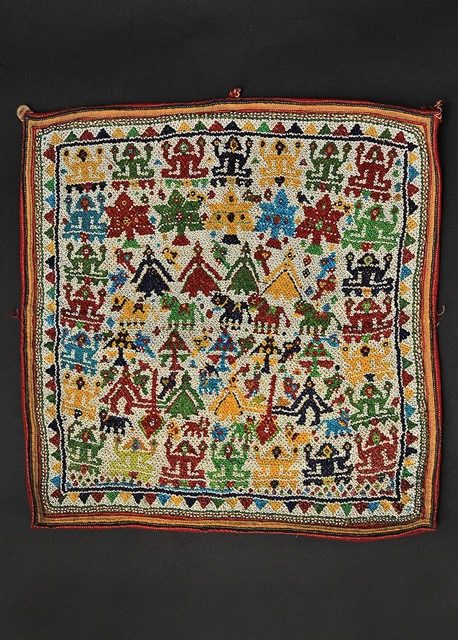

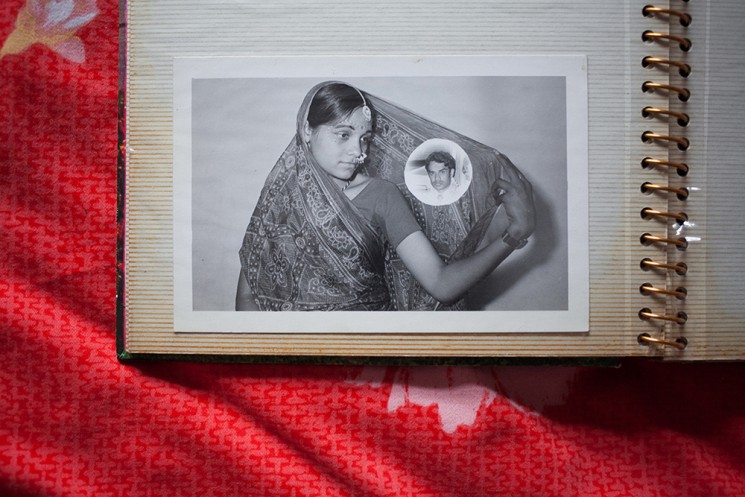

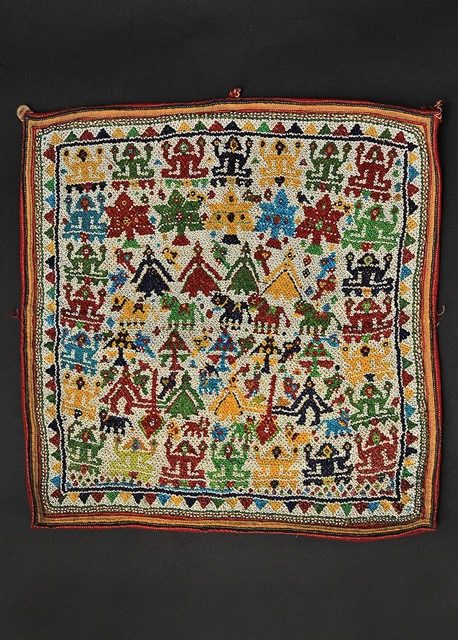

A vibrant display of textiles, metalwork and other materials captures the resilience and the creativity of these displaced Gujarati communities, and shows both how they strove to preserve the art, language, food, literature and religion of their people and also how these were in turn adapted by the countries to which they migrated. It shows how the ‘dukawallah’, who established shops and stores along the east African train line, went on to set up corner shops and stores in Britain and other Western countries, in the process contributing to the change in shop opening hours that eventually led to Sunday trading. It demonstrates how the culture of the people shrugged off differences in religion and belief (the state of Gujarat, while predominantly Hindu, also had significant Muslim, Sikh, Jain and Zoroastrian populations) and how indeed these differences often refashioned cultural templates, which you can see in particular in the evolution of different textile forms. And it reveals – through its stories of everyday racism, the Grunwick strike and the extraordinary success of certain individuals – aspects of migration and settlement that will be familiar to people from different cultural backgrounds.

Beaded square piece.

Intriguingly, from the Migration Museum’s point of view, many of the decisions made by the two curators of the exhibition, Rolf Killius and Lata Desai, match decisions made in our own exhibitions – and vindicate the approach! Not only have almost all the artefacts on display been loaned to the exhibition by ordinary citizens, but the examples of embroidery and other stitchwork adorning the walls downstairs in the cafe area are also all the product of people who have attended the workshops run as part of the overall exhibition. Many of these pieces have been produced by people who had not stitched anything before attending the workshop. In addition, the oral testimonies that accompany the individual displays represent precisely the kind of spoken record that we aim to develop in our own Migration Museum.

Rajkot Patodu sari.

Gujarati Yatra has received Heritage Lottery Funding allowing it, after April, to migrate to a digital format so that it will be available for a further seven years as an online collection. All oral history interviews, the edited films, photographs and texts will go online on a dedicated website: www.gujaratiyatra.com

The whole display is a wonderful, colourful, affirmative account of the ability of a people to navigate its double diaspora and to keep intact its spirit and its sense of cultural identity. We urge you to go and see it!

1As part of the same exhibition, Croydon Now Gallery showcases oral histories and travelling objects (to 14 April 2018), and there is a sari exhibition in the Clocktower atrium (to 26 February 2018) and an embroidery exhibition in the Clocktower Café (to 27 January 2018).

Gujarati Yatra is open until 14 April February in Croydon Now Gallery, and a season of events has been woven around its six-month residency – family days of art and crafts, talks, film screenings, literary events and dance productions – all designed to show how the Gujarati identity is maintained in the UK. The curators are currently contacting other museums and community organisations in order to tour the exhibition to other places in the UK.

23 May, 2016

Kajal Nisha Patel’s photographs have long been favourites of ours and of visitors to our exhibitions. There’s a richness to their colour and a vibrancy in their composition that people love, whether in the slyly provocative ‘Nagar Kitan’ (which Kajal previously called ‘No, this is England’) or ‘The Patriot’ or her shot of a pair of Union Jack socks on the feet of an unidentified model. They are also a wonderful reflection of their location, Leicester, which is one of the reasons why they were used to such winning effect both by BBC Radio Leicester and by the University of Leicester’s School of Museum Studies, when 100 Images of Migration was being re-curated by the School in 2013–14. We’re immensely grateful to Kajal for allowing us to use so many of her images, but, weirdly, she’s almost as grateful to us: she feels that our use of her photos has allowed her to reach audiences and opened up prospects that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise. Whereas I think the strength of her photographs would break down most doors and that we’re ridiculously privileged to have been able to make such use of them.

Nagar Kitan, Leicester, 2011 (previously known as ‘No, this is England’). Leicester’s annual Sikh Vaisakhi parade normally attracts around 30,000 worshippers from all around the UK. © Kajal Nisha Patel

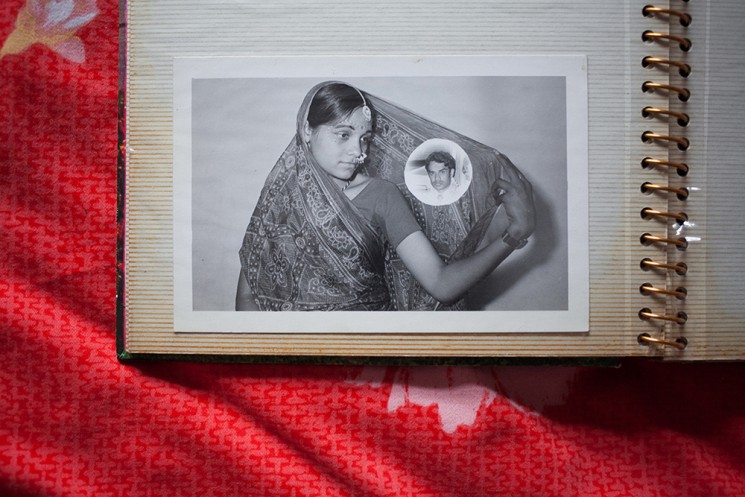

So it’s a bit of a surprise to find, on meeting her in the University of Leicester Union Diner, that she has fallen slightly out of love with photography. Currently the Leverhulme Artist in Residence at the University of Leicester, a position she holds until December 2016, she is looking to develop as an artist in ways that will take her beyond photography to something that is more inclusive and immersive. She worries about the reductive nature of photography: ‘When I’m taking a photograph of a person, there is always a third person present in the portraiture: the person who will eventually be looking at this photograph in an exhibition or an online display of my work.’ It’s the reason she has such nostalgia for found and vernacular photography, pictures that were always solely intended for the people being photographed and the person taking the photo. Any artistry such pieces had, she says, was completely accidental – and the better for that. Continuing this riff, and despite having brought her huge Canon with her to our meeting, Kajal wonders whether from now on her photographs will mostly be taken on her phone, to get back to this idea of vernacular art. To illustrate the point, she shows me a picture she took in the past few days of her father bending down to sweep up around the skirting board in the kitchen. It’s a spectacularly beautiful image – capturing the light and the humanity of a prosaic gesture in exactly the way that her other images do. Kajal, rather ruefully, agrees with me when I say so. ‘Yes, I can see what a good composition it is,’ she says, ‘but that had nothing to do with the reason I took it. I took it because I was moved to see my father – an Indian man of his generation – so comfortably involved in a domestic task that would traditionally be seen as a woman’s duty. That’s what I wanted to show.’

Dad, 2016 (Kajal’s father in the kitchen of his home in Leicester, taken on Kajal’s phone). © Kajal Nisha Patel

Domestic roles, the working lives of women, how women can become emancipated, physically and spiritually, the relationship between mother and daughter, these are Kajal’s preoccupations as she moves into her residency. We talk about the powerful message of the East African Asian migration to Leicester: how the dearth of job prospects for men arriving in the dying throes of Britain’s prowess as a manufacturing nation led to women performing a textile revolution, at the same time transforming the economic fortunes of the city and doing so, ironically, by overturning the standard domestic roles of men and women in their community.

Mum and Dad, 2016. © Kajal Nisha Patel

Kajal agrees but points out that it’s more complicated than that – that women and mothers continue to be oppressed on any number of levels and that, again ironically, for many Asian women becoming wives and mothers represented a kind of emancipation: their new status gave them a role and an arena in which to perform it that they wouldn’t have had if they’d continued to live with their families. Kajal wants to explore this further and to see how these roles led the Asian women of her mother’s generation to develop further life skills, some of them, by any definition, creative skills.

Former factory, Frog Island, 2010. © Kajal Nisha Patel

There’s a neat circularity in what she is trying to do at the moment, too. She says that the arts are not really valued in the Asian community, where knowledge is the highest source of wealth and work is the most potent currency. So she made work her focus, touring around factories to seek out the stories of workers (mostly women), gleefully documenting the story of the 1972 Mansfield Hosiery strike in nearby Loughborough, in which a predominantly Asian female workforce stood up against discrimination in the workplace. ‘Our very own Grunwick dispute, though with less media coverage,’ says Kajal, ‘But it made me feel so proud to find out about it.’ She’s currently producing five films about the strike, looking at the tensions or the balance between the working and the domestic lives of the participants.

Birds, Frog Island, 2010. © Kajal Nisha Patel

Out of work, art. There’s a ‘Yes, but … ’ there, because Kajal has problems with the art establishment: art galleries continue to be elite institutions, with obvious barriers, especially for Asian artists, and it’s still complicated getting BME art shown elsewhere. It’s why Kajal hopes to be working extensively in schools and the workplace, nurturing a sense of self-reliance that she hopes will be politically emancipating, too. There’s a political fire to everything she talks about – whether it’s the connection between climate change and migration, the link between migration and happiness (the key concern of David Bartram, her mentor for her residency), the subject of identity (as big an issue, Kajal maintains, for white British men as it is for British Asian women), the trade relationship between India and Britain. I get so taken up in the conversation that I fail to notice that we are having lunch in an otherwise deserted restaurant at 3pm, which in turn means that I end up missing my train back – something that Kajal seems to feel worse about than I do. As an artist, she works on a very tight budget, and any unexpected expense causes consternation. Though I too am concerned, I feel that I’ve more than got my money’s worth from the day. I’ve found out a lot more about a city that has been a very good friend to the Migration Museum Project, I’ve done so in the company of a photographer who has been one of our most generous supporters, and the chana massala and mattar paneer that made me late for my train were the tastiest I’d had in a long time. All of that more than makes up for the cost of an extra ticket.

There is a ‘Yes, but … ’ for me, too, but it’s not about the train fare. What I wanted to say to Kajal before I left was, yes, of course go ahead and do this work that so fires you and stokes your interests, and for which I know you’ll produce something really special. But there are a lot of people out there who love your photos for their effortless grace and power – so don’t forget to take the occasional photograph, too.

Kajal’s work can be viewed on her website, www.kajalpatel.com (currently under construction); the project for her work as Leverhulme Artist in Residence can be followed at www.kajalpatel.org, and her Twitter feed is .