Karl Marx’s London

Much is made of Britain’s reputation for providing refuge for people seeking political asylum but many consider such self-congratulation undeserved, pointing instead to Britain’s relative resistance to taking in Jewish refugees before and during the Second World War, to the small number of Vietnamese boatpeople taken in in the 1970s (in comparison with those taken in by the United States and France) and, more recently, to a governmental reluctance to accept refugees from the Syrian civil war. And yet the historical record of political dissidents being given sanctuary in Britain is clear, and this seems particularly to have been the case in the 19th century, when arguably the most famous political dissident, Karl Marx, made London his home for the last 34 years of his life.

In this guest blog, Dr Thomas C. Jones, lecturer in history at the University of Buckingham and producer of the audio walking tour ‘Marx’s London’ (available as a History Workshop podcast), outlines Marx’s passage from poverty-stricken Soho to the then suburban Kentish Town.

Refuge from a reactionary continent . . .

A depiction of jubilant crowds in Berlin at the beginning of Germany’s revolution in March 1848

In the aftermath of the failed European revolutions of 1848, thousands of political exiles sought refuge in Britain. Almost alone in Europe, Britain had no significant immigration restrictions and its maintenance of a free press and rights to free speech and assembly made it particularly attractive to the disappointed revolutionaries streaming out of Europe as reaction spread across the continent. By 1852, some 7,000 radical, nationalist, republican, and socialist refugees from France, Hungary, Poland, the German and Italian states, and elsewhere had arrived, clustering above all in London. In their midst were famous individuals like the Italian nationalist Giuseppe Mazzini, the French socialist Louis Blanc, and the leading light of the Hungarian independence movement Lajos Kossuth. They were joined by many much more obscure exiles, including a thirty-one-year-old philosopher and journalist from the Rhineland region of Prussia in western Germany, Karl Marx. Marx, who had successively been expelled from Prussia, France, and Belgium, was at this time a rising star in the small European socialist movement, having written for several radical publications throughout the 1840s, co-authored The Communist Manifesto with his friend and collaborator Friedrich Engels in early 1848. Like many other exiles, Marx expected revolution to break out again soon and for his stay in London to be temporary. In fact, he would remain for the rest of his life.

1 Leicester Street, London, the former site of the German Hotel.

20 Great Windmill Street, the former site the Red Lion pub.

Marx arrived in London in August 1849 and was soon joined by his wife and childhood sweetheart Jenny von Westphalen and their children Jenny, Laura, and Edgar. The family first stayed in the German Hotel near Leicester Square, a popular destination for Germans in London. Their first flat, in Chelsea, proved far too expensive and they were quickly evicted for failing to make rent. On the suggestion of Heinrich Bauer, another German refugee, they moved to Dean Street in Soho, first to a modest two-room flat at number 64 in May 1850 and then in December to number 28, into a flat they managed to expand to three rooms after about a year.

This put the Marxes at the heart of refugee London. A cheap district with a long history of immigration, Soho was a natural gathering place for exiles after 1848, and many English commentators marvelled at the growing multinational population to be found in the neighbourhood’s tangled streets. One article in Charles Dickens’s newspaper Household Words from 1853 remarked on simultaneously encountering ‘ex-representatives of the people’ from France, German ‘scientific conspirators’, ‘swarthy Italians’, Hungarians with ‘glossy beards and small embroidered caps’, and Poles ‘who have been so long fugitives from their country’. Foreign-language newspapers and bookshops soon sprang up to service this population, as did numerous shops, restaurants, taverns and other meeting places owned and frequented by the refugees.

For the roughly 1,000 German refugees in London in the early 1850s, a key social and political centre was the Red Lion pub at 20 Great Windmill Street. This housed the London branch of the Communist League, a small but international organisation for which Marx and Engels had written The Communist Manifesto. It was also home to the German Workers’ Educational Society, which was founded in 1840 and lasted into the twentieth century. Marx was active in both organisations, arguing politics with his fellow refugees in the former and teaching classes on economics and running a relief committee for poor exiles in the latter. A short walk from Dean Street, the Red Lion was also a welcome social outlet where Marx drank, smoked, dined, and played chess with his countrymen. More generally, the Marxes enjoyed an active social life in Soho, often hosting gatherings of exiled or visiting Germans, frequenting the district’s pubs and restaurants, and taking weekly walks on Sundays to picnic on Hampstead Heath.

The site of Marx’s home at 28 Dean Street.

The ‘blue plaque’ was put up by the Greater London Council to commemorate his residence.

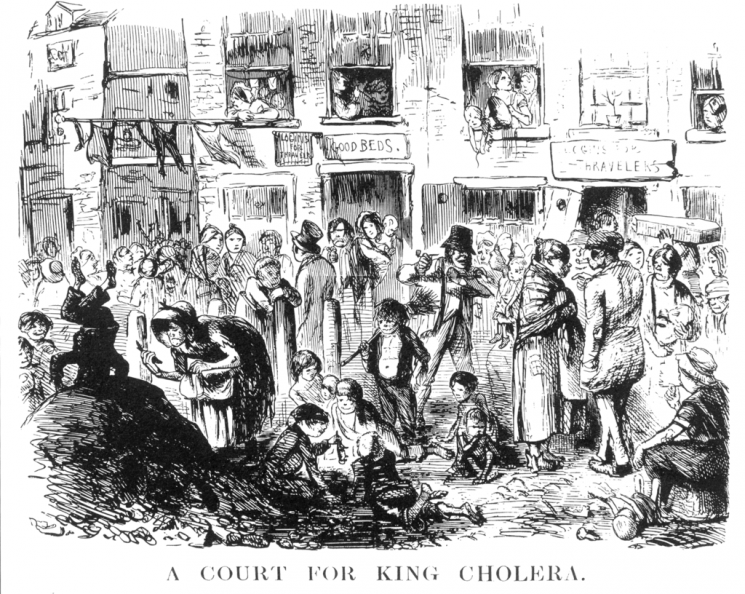

The cartoon ‘A Court for King Cholera’ from “Punch” in 1852, depicting squalor in urban districts like Soho.

A photograph from 1864 of (left to right) Marx and Engels standing and Marx’s daughters Jenny, Eleanor and Laura seated.

The site of Marx’s home on Maitland Park Road, near Kentish Town.

A commemorative plaque set up by Camden Council.

Yet, as the 1850s wore on, the family’s fortunes improved. Marx gained steadier income as a European correspondent for the New York Daily Tribune, the largest newspaper in the world at the time. Between 1852 and 1862 he and Engels, who provided crucial assistance with Marx’s written English, published 487 articles explaining European and global affairs to an American audience, often earning more than £100 a year in the process. In 1856, Jenny received two bequests worth a combined £270. These were substantial sums in that era and allowed the Marxes and their surviving children, Jenny, Laura, and Eleanor, to leave Soho.

In September 1856 they settled in an eight-room house in 9 Grafton Terrace, in Kentish Town. This was a newly urbanised neighbourhood, one of the areas engulfed and developed by the rapid growth of London facilitated by the railways. It therefore had the feel of a building site, and Jenny complained that ‘one had to pick one’s way over heaps of rubbish and in rainy weather the sticky red soil caked to one’s boots so that it was after a tiring struggle and with heavy feet that one reached our house’. Yet these difficulties were outweighed by the benefits of increased space, giving Marx room for a proper study and privacy for the by-now adolescent girls. Indeed, they would remain in the area for the rest of their lives. In March 1864, as Marx inherited a combined £1,500 from his mother and from his friend Wilhelm Wolf, the family moved to a nearby house at 1 Modena Villas. The house’s £65 annual rent and £4 8s property rates (£4.40 in today’s money – but worth a lot more at the time) were substantial and would have given Marx the right to vote even before the widening of the franchise by the Reform Act in 1867, had he been a British citizen.

18 Greek Street, where the International’s General Council met.

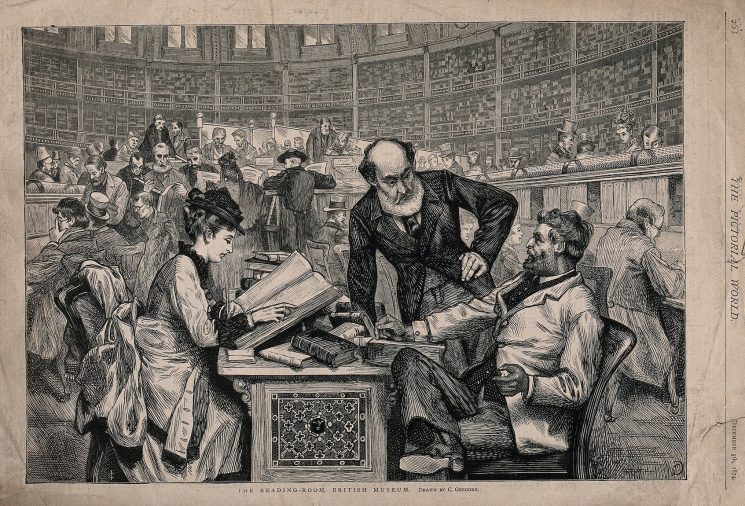

‘The British Museum: the interior of the reading room, in use. Wood engraving by [I.C.] after C. Gregory, 1874’ by Charles Gregory. Credit © Wellcome Collection

Marx’s tomb in Highgate Cemetery, where he, Jenny, their daughter Eleanor, grandson Harry Longuet, and Helene Demuth are buried.