Archives

3 December, 2017

The Migration Museum Project is blessed with a large team of fantastic volunteers, without whom we would find it hard to function and impossible to run our events and exhibitions. Assunta Nicolini is one such volunteer, and her discussions with visitors to our current exhibition, No Turning Back, have got her thinking about a number of issues that she feels are raised by the display. This blog is the result of her thoughts and discussions around two of the seven moments of the exhibition: the arrival in this country of Huguenot refugees after 1685, and the passing of the Aliens Act in 1905.

No Turning Back: Seven migration moments that changed Britain introduces visitors to powerful artworks and archive images carefully interwoven to create a narrative that brings together past and present. It is within history that we so often find the key to understanding many of the social realities we inhabit today.

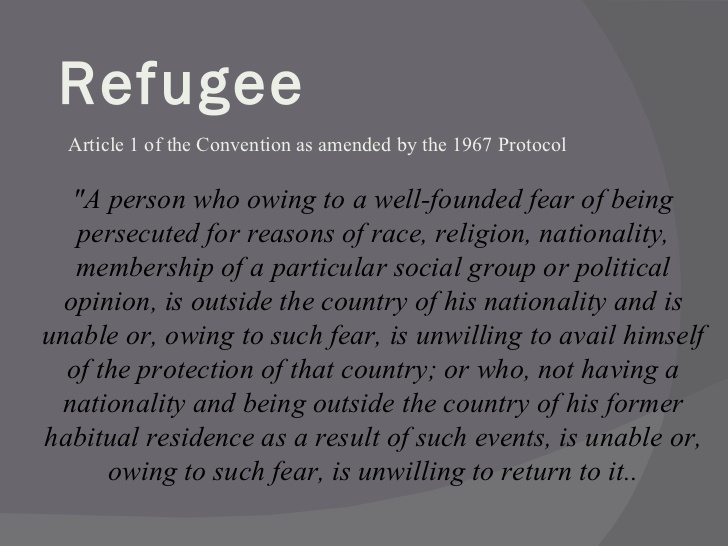

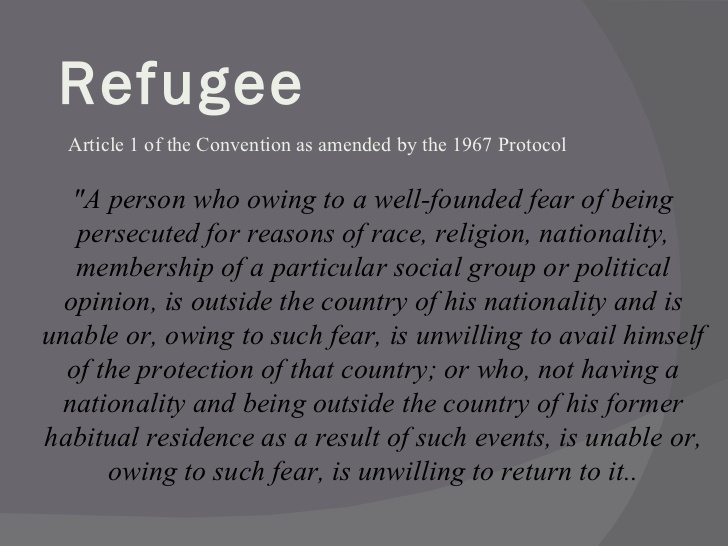

Migration is no exception. One of the seven moments shown in the exhibition, the year 1685, holds a particular relevance in the understanding of today’s migration dynamics.It was the year that France made Protestantism illegal, precipitating the arrival in Britain of about 50,000 French Protestant Huguenots. Centuries before the drafting of the Refugee Convention (1951), and with no legal framework in place establishing roles and responsibilities towards people escaping persecution, the term ‘refugee’ was introduced into the English language through the French Huguenots arriving on British soil in search of protection (refuge). It took about three centuries, a series of major humanitarian crises and, ultimately, the horror of the Holocaust for the international community to establish a legal framework aimed at giving protection to people fleeing persecution.

Article 1 of the United Nations’ 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.

The history of the Huguenots in Britain is not, however, just about one of the largest refugee groups to seek safety and protection in this country. Their life experiences were not simply defined by their ‘refugee-ness’; on the contrary, their arrival and settlement offer just as important insights into the realities of migration.

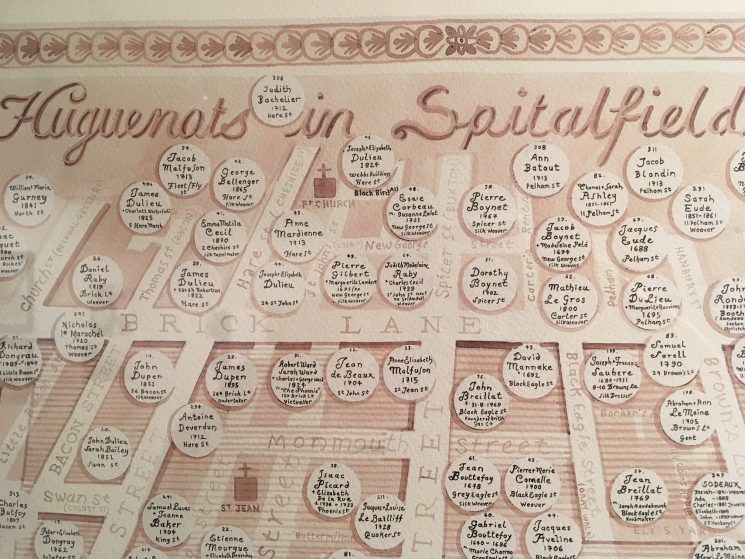

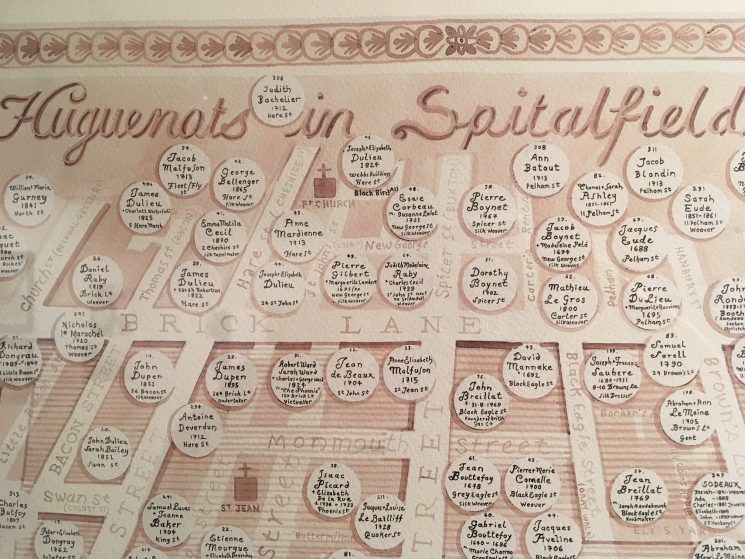

In the exhibition, Adam Dant’s delightful map representing this historical moment takes the curious eye of the visitor through a detailed drawing of the streets surrounding East London’s Spitalfields Market. Surnames of French origin are circled to indicate where the Huguenots were to be found. As visitors adjust their eye to these several locations, they then notice a further, more crucial detail. Surnames are accompanied by ‘professions’, mainly artisanal, such as weavers, clockmakers and silk merchants.

A detail from Adam Dant’s ‘Huguenots in Spitalfields’. A range of professions are readable in these circles, for example: ‘silk weaver’, ‘undertaker’, ‘victuailler’, ‘reed maker’ and ‘gent’. © Adam Dant

Such detail is crucial as it allows the visitor to expand their understanding of who these people were, beyond the one-dimensionality of their ‘refugee-ness’. Being given protection in Britain was not the end of the Huguenots’ ‘migration journey’ – settling and restarting their lives, as well as providing for their families, was just as important. Historical archives tell us that, although the Huguenots left France clandestinely and at short notice, taking little with them and with limited time for planning ahead, they were nevertheless aware that certain destinations were better than others. London, for example, offered not only protection but also great opportunities for employment and hence a better place to settle.

You don’t need to be an expert to spot the striking similarities with contemporary experiences of migration. Today’s refugees are no different from those of centuries ago – like them, they are human beings who, in order to have a life beyond survival, need to work. Obvious though this point is, the current obsession in the media and parliament is the apparent distinction between ‘refugee’ and ‘economic migrant’.

It is possible, however, to make such complexity simple, and to offer an accessible understanding of such migration dynamics. Migration experts have been drawing attention to the fact that immigration statuses – the classification of refugee, migrant or asylum seeker, for example – are never fixed but on the contrary are dynamic and mobile.1 Rigid legal categories labelling individuals either as migrants or refugees have become increasingly obsolete, as they fail to reflect the personal and global realities of contemporary migration.2 The stories of refugee-migrants themselves consistently show that people might start their journey as refugees but, like the Huguenots, become economic migrants later on. Scholars have widely recognised that contemporary migration is defined by its mixed nature and by continuity, rather than an opposition between forced and voluntary migration (see this video for Dr Nicholas van Hear’s clear outline of this matter).

The overlapping and mobility between immigration statuses is an aspect that was overlooked at the the time the Refugee Convention was drafted. Understandably, soon after the Second World War, the concern of the international community was focused predominantly on making sure that persecuted people would be protected outside their home countries. Economic migrants, on the other hand, could not benefit from a specific legal framework protecting their rights, since the ‘voluntary’ dimension of their migration implied they took responsibility for their own protection.

In recent decades, however, a greater emphasis has been placed on additional legal frameworks aimed at correcting the shortcomings of the Refugee Convention, in particular those based on International Human Rights law. A rights-based approach can in fact not only provide a framework for the protection of economic migrants but also enhance refugees’ protection, while at the same time establishing the universal human right to seek asylum.

Despite the availability of different legal frameworks governing migration and ‘refugee-ness’ today, there is no agreed position in policy making, advocacy and public opinion. Public opinion is characterised by narratives of ‘good and bad’ refugee-migrants, of ‘deserving and undeserving protection’, and of ‘inclusion and exclusion’. Refugees are mostly perceived as victims, but the moment they display willingness to economically improve their lives they are automatically seen as economic migrants and hence as undeserving of protection and support.

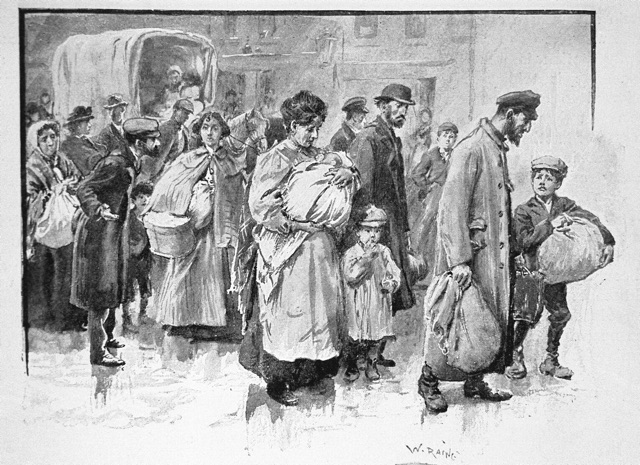

Satire on the Aliens Act – drawing of Britannia turning away a group of refugees who have just disembarked at a port, 1906. Part of the Migration Museum Project’s ‘No Turning Back’ exhibition. Image courtesy of the Jewish Museum.

Far from being new, this narrative partly finds its roots in another pivotal migration moment shown in the exhibition – 1905, when the Aliens Act was passed in Britain, the first legal framework regulating migration and based on the notion of ‘desirable’ and ‘undesirable’ immigrants. The Aliens Act was the result of rising nationalism based on disproportionate fear about newly arrived refugees, mainly Jews, and migrants of Asian origins. A satirical drawing from the time, showing Britannia saying ‘I can no longer offer shelter to fugitives; England is not a free country’, aptly describes the feeling of rejection felt by Jewish refugees. Another pamphlet from the archives directs the visitor’s attention to the fact that rejection was felt not only by refugees but also by immigrants, with trade unions attempting to dismantle the unfounded belief that migrants were competitors in the job market and bad for the British economy. Through the various details of this migration moment, the visitor is also encouraged to think about the importance of keeping labour migration channels open to refugees today.

History reminds us that looking at migration through rigid binaries of ‘desirable’ and ‘undesirable’, ‘deserving’ and ‘economic’, risks reinforcing a dangerous divide that often underpins much of public opinion and policy making. What we witness today and the stories that migrants and refugees tell us bear a profound resemblance to the past and urge us to consider that a refugee-migrant should not be seen as a threat but rather as an asset to Britain and host countries in general.

1 See, for example, Schuster, L (2005) ‘The Continuing Mobility of Migrants in Italy: Shifting between Statuses and Places’. Oxford: COMPAS and Bloch (2011)

2 Zetter, R (2007) ‘More labels, fewer refugees: remaking the refugee label in an era of globalisation’, Journal of Refugee Studies, Volume 20, Issue 2, 1 June 2007, 172–192, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fem011

21 October, 2016

We went on a walk last Sunday, along with about 130 others.

It started in the cold, grey and wet, at a time when many of us would still be, if not in bed, certainly doing nothing much more energetic than turning the pages of a Sunday paper and slurping coffee. It ended in glorious early-evening light, with a rainbow over the Serpentine and, if not actual gold at the end of the rainbow, then the next best thing – cakes and prosecco.

Somewhere over the rainbow … Looking east from the Lido café in Hyde Park, the end-point of our Imprints walk. © Faiza Mahmood

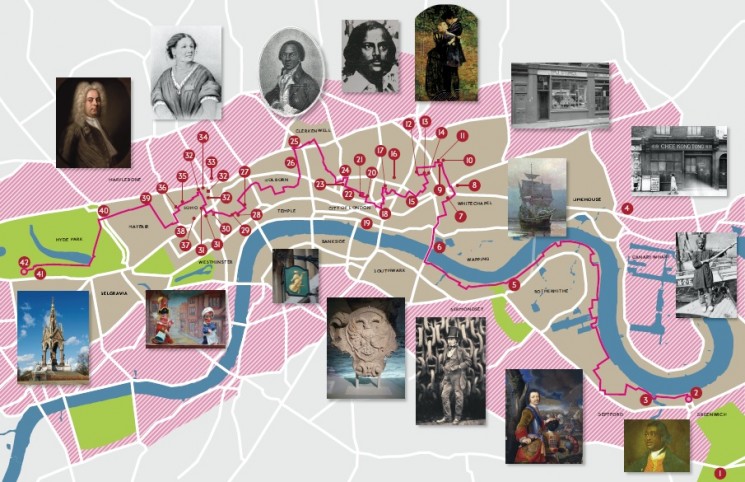

It started in Greenwich, where so many migrant stories have started in the past – George I prominently among them, borne to his disembarkation at the Old Royal Naval College aboard the ship Peregrine, but also, though much less regally, Ignatius Sancho, born on a slave ship and later a lobbyist for the abolition of the slave trade. It ended in Hyde Park, just short of the Albert Memorial, flamboyant statue to one of the most-loved migrants of the nineteenth century and the inspiration for the cluster of museums and institutions – Albertopolis – that now draw so many visitors to our capital.

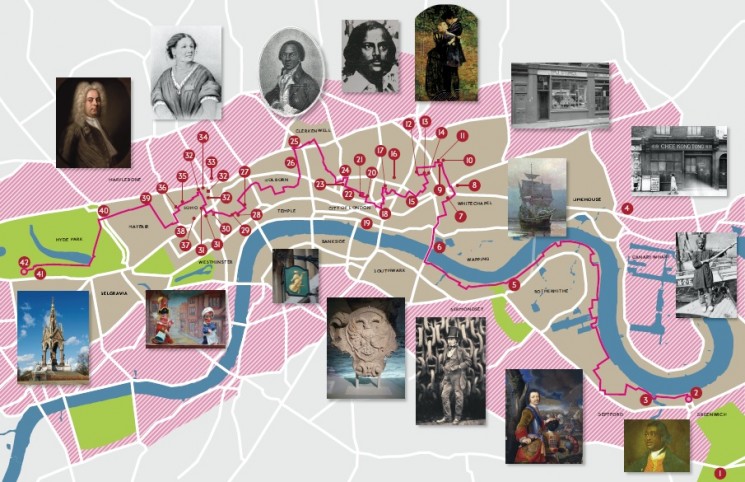

The outline of the route the Imprints walk took through London. © Brandingbygarden

Not all migrants migrate from east to west of the city, of course, but it’s a useful hook to hang an event of this kind on. It’s certainly a long walk, that walk from arrival to establishment, and not all migrants make it with equal success, happiness and good fortune. And it was a long walk, literally, on Sunday, a full 15 miles and counting, which not all participants made with equal success, happiness and comfort of foot. But the overwhelming majority of those who started the walk completed it, and there was a sense of euphoric satisfaction in Hyde Park at the end of the day that may have had something to do with the prosecco on offer, or possibly with the sheer relief of the walk now being at an end – but which was mostly down to the sense of fulfilment and enjoyment of a day spent in good company, learning something about the myriad migration stories that make up the history of London, and of the multiple layers that make each street and region a palimpsest of the migratory experience: whether it’s the Brick Lane Jamme Masjid mosque, in a building that had previously been a synagogue and was, before that, a Huguenot chapel; or the building in Old Jewry, now housing the visa office for the People’s Republic of China but almost eight hundred years previously the site of the first synagogue in this country; or 25 Brook Street, home to George Frideric Handel in the 1700s and the more raucous stomping ground of Jimi Hendrix in the 1960s.

The Jamme Masjid mosque in Brick Lane – previously a synagogue and, before that, a Huguenot chapel. Spectacular minaret sadly not shown. © Aditi Anand

Divided into groups of 10 to 15, each led by an incredibly well-versed volunteer guide and supported by one of our magnificent volunteers, we walked along the south bank of the Thames to Tower Bridge, meandered through the East End, Brick Lane and Spitalfields, wandered through empty and storm-soaked streets in the City, rising again into Clerkenwell and Holborn – passing through the world of clockmakers, jewellers, lawyers and artists, before moving westwards through Covent Garden, Soho, Kensington and Mayfair. In Postman’s Park, Bill Bingham (our very own Ian McKellen) appeared out of nowhere, surprising us with a rendition of Shakespeare’s Thomas More speech (‘Grant them removed, and grant that this your noise / Hath chid down all the majesty of England … ’), delivered (in theory) in the early 1600s to quell riotous discontent at the arrival of the Huguenots. We stopped along the way to hear the story behind particular buildings, or about individuals who had lived in that area, or whole movements of people; and in-between we talked to each other about our own stories, about plans for the Migration Museum Project, about how our country would change in the wake of the recent referendum decisions.

Emily Miller, the MMP’s education manager, in Chinatown with Isabel Morrison. © David Wigram

We liked it so much we are already planning to do it again next year – at least once more in full length, and maybe on a number of other occasions, in a shorter form. And already we’re thinking, if this works so well in London, why wouldn’t it work just as well in any number of other cities: Newcastle, Manchester, Glasgow, Liverpool, Belfast, Bristol, Leicester? Get in touch with us if you want to help us plan how to extend it.

Oh, and we raised hugely important funds for the MMP’s work, too. Our target was to raise £20,000 to enable us to continue delivering exhibitions, events and education work in schools as we build the case for a permanent Migration Museum for Britain. At the time of writing, we are still a little short of our target – the equivalent of finding ourselves in Regent Street, when we need to be in Hyde Park. If you would like to help us reach our target or destination, please go to our MyDonate page.

And, just in case you can’t quite take our word for it, have a look at what some of the walkers had to say about the experience:

Epic day with informed guides – great fun despite the rain!

What a fab day! Like walking through a spread of London’s amazing history!

A wonderful way to explore London and discover how migration is a fundamental part of the city’s identity.

Amazing experience, informative and enlightening. Highly recommend it

I enjoyed seeing so much of London in one go, and learning about all the little histories and significances that would have gone unknown otherwise.

I loved the content and it’s great to have the map as a momento. Lots of highlights that I have been boring my nearest and dearest with: Mayflower pub selling US stamps – Rotherhithe tunnel used to have shops! – De Hems pub history … and of course the wonderful performance in Postman’s Park, a speech which I didn’t know and now love.

Very interesting, and I learned lots! Like the fact that it was easier to be black than Catholic in Tudor England! It made me think about things in a totally new way – I hadn’t thought of Paul Reuter as a German immigrant to London before!

We went on a walk last Sunday. It was a huge success, raising funds and fun in equal measure. Why don’t you come on the next one we organise?

The first Imprints: London Migration Walk took place on Sunday 16 October 2016. Huge thanks to our team of volunteer guides, all of whom were mines of information, wit and inspiration – and to the volunteers who supported them. Without you, this project would be struggling! But the biggest thank you goes to the 130 participants who so good-naturedly and energetically gave up their Sunday to support us on the walk, and did so without complaint, even when the skies emptied their load on us in the early afternoon. Thank you, thank you, thank you. Here’s to the next one!

3 August, 2016

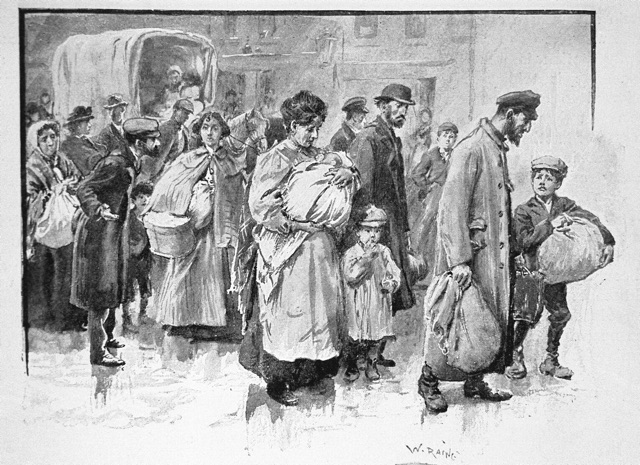

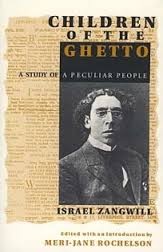

What was the attitude of the Victorians to immigration, particularly Jewish immigration? What was the mood of the country leading up to the passing of the Aliens Act in 1905? And what parallels are there between the experience of immigrants then and now, one hundred years later? The focus of this guest blog is Israel Zangwill and his late-19th-century book Children of the Ghetto; Nadia Valman, who has created an app that allows people to explore the Spitalfields area through the medium of the book, flags up a surprising number of parallels between the two periods.

Children of the ghetto

Israel Zangwill’s 1892 novel Children of the Ghetto is a landmark publication in English literature: the first Victorian novel to offer an insider’s perspective on immigrant lives in London. It offered the reader a wide social panorama, including rabbis, schoolteachers and philanthropists, garment workshop bosses and machinists, socialist organisers and poets, immigrant parents and English-born children. Published to great acclaim at a time of rising popular feeling against immigration, the novel aimed to make a significant political intervention by fostering understanding of a mostly voiceless migrant population.

Zangwill was in a unique position as a writer. He had lived most of his childhood in Spitalfields, the area of east London where tens of thousands of Jews, fleeing pogroms, expulsions and economic restrictions in the Russian empire, had settled during the 1880s and 90s. As a teacher at the Jews’ Free School there, he worked among the children of immigrants, most of whom entered school speaking no English. But as a graduate of London University who had moved to Bloomsbury and renounced religious practice, he also observed the Spitalfields Jews at a distance. His novel documented the close ties felt among people who, he wrote, had been forced to live in isolation for centuries, and could not easily shrug off the weight of that history.

Children of the Ghetto blasted onto the literary scene in the year of a general election in which immigration was a hot political topic. Back in the early 1880s, there had been widespread sympathy for the plight of Jews escaping persecution and destitution, and large protest meetings in cities all over the country condemned the Russian pogroms. Soon, however, attention turned to the social impact of immigration. Spitalfields, often referred to as the ‘Jewish colony’, attracted the fascinated gaze of sociologists and journalists. ‘My first impression on going among them,’ wrote Mrs Brewer in the Sunday Magazine in 1892, ‘was that I must be in some far-off country whose people and language I knew not. The names over the shops were foreign, the wares were advertised in an unknown tongue, of which I did not even know the letters, the people in the streets were not of our type, and when I addressed them in English the majority of them shook their heads.’ Others reacted with antagonism rather than bewilderment. The anti-immigration campaigner Arnold White declared that, unlike Christian refugees to England, Jews formed ‘a community proudly separate, racially distinct, and existing preferentially aloof … A danger menacing to national life has begun in our midst,’ he warned, ‘and must be abated if sinister consequences are to be avoided.’

As with other immigrants before and since, the Jewish immigrants of the 19th century introduced new tastes and refinements to London.

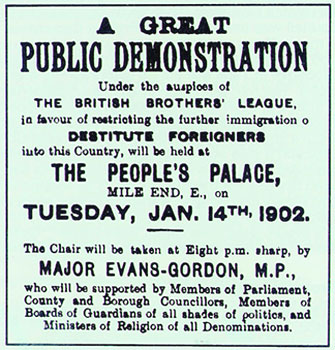

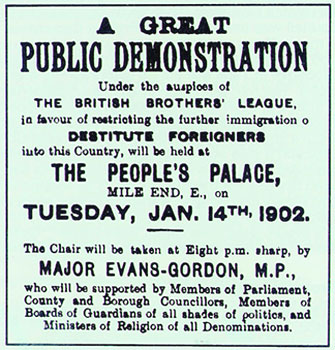

By the early 1890s a group of Conservative back-benchers were increasing pressure on the government to control immigration. The failure of their efforts in the following years has been attributed by some to the impact of Children of the Ghetto. But rising unemployment and discontent at the end of the decade provided the opportunity for two East End Conservative MPs to form the British Brothers League, which aimed to galvanise local support. A mass rally in January 1902, held at the People’s Palace, Mile End Road, was advertised as a ‘great public demonstration in favour of restricting the further immigration of destitute foreigners into this country’.

The British Brothers’ League was formed in 1902 to campaign against immigration; it was organised on vaguely paramilitary lines. Dribbling into obscurity in 1923, the League was in many respects the precursor of the British Union of Fascists, which had a significant and unsavoury presence in the 1930s.

It was partly in response to this popular hostility that the first immigration restriction act for a century was passed in Britain – the Aliens Act of 1905. The Act, while retaining the right to asylum on political or religious grounds, gave government inspectors power to ‘prevent the landing of undesirable immigrants’, including ‘invalids’ and ‘paupers’ – those who could not show that they were capable of supporting themselves – and thus excluded not only the sick and elderly but also those who arrived destitute, often having been conned or robbed of their assets on the journey.

There are many resonances between popular anti-immigrant feeling then and now. In the early 20th century, it helped to channel and defuse Eastenders’ anger at their chronic poverty and insecurity. Jews were accused of lowering the standard of living with ‘sweatshops’ – small workshops characterised by poor working conditions, long hours, low pay and seasonal fluctuation, and of causing the housing shortage that had led to extreme over-crowding. Yet in fact both problems were rife in the East End long before the Jews’ arrival. Hostility to immigrants came from pervasive lack of understanding about the real economic causes of local unemployment, such as trade depressions, mechanisation, and competition from manufacturers in the provinces.

In this context, there was considerable pressure on Israel Zangwill to produce an uplifting account of Jewish Spitalfields, countering misconceptions and demonstrating how Jewish immigrants were contributing positively to the economy and living pious, law-abiding lives. That pressure is evident in aspects of the immigrant subculture that he deliberately left out of the novel: the gang violence, the prostitution, and gambling clubs.

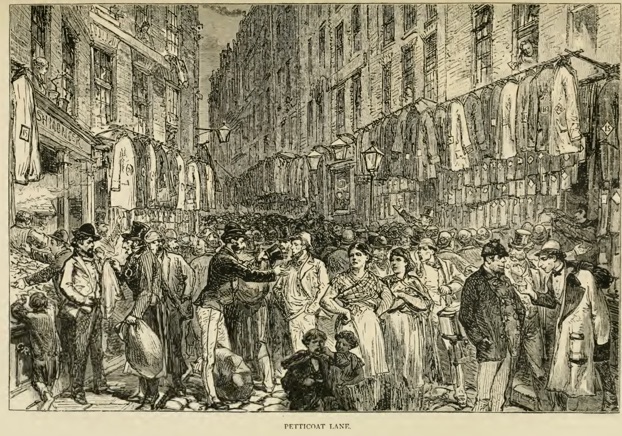

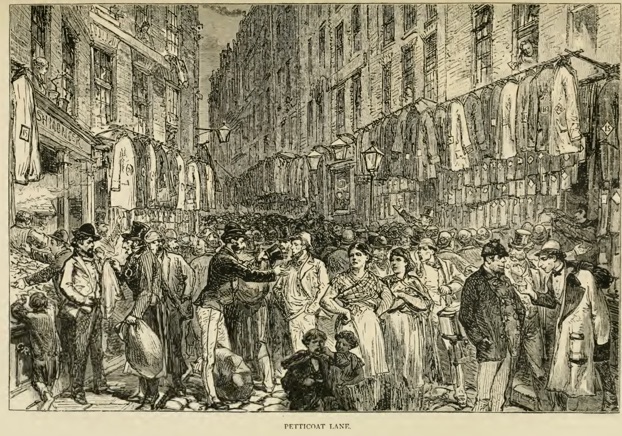

Nonetheless, Zangwill took a bold stand against a number of contemporary stereotypes. Petticoat Lane market, for example, at the heart of the immigrant area, was invariably associated in the Victorian press with danger and dodgy dealing, but it has a very different meaning from Zangwill’s perspective. He describes Petticoat Lane as a place where Jews of all social classes congregate to experience the smells and tastes that remind them of their roots.

Petticoat Lane, 1878.

‘The Lane was always the great market-place,’ he writes, ‘and every insalubrious street and alley abutting on it was covered with the overflowings of its commerce and its mud … The famous Sunday Fair was an event of metropolitan importance, and thither came buyers of every sect … A babel of sound, audible for several streets around, denoted Market Day in Petticoat Lane, and the pavements were blocked by serried crowds going both ways at once.’ In his account of the market, Zangwill emphasises its vitality and vulgarity. The distinctive dynamism of immigrant culture, for him, was precisely what was valuable about it. But the market was far from being a ‘ghetto’: it was here that Jewish culture was shared with ‘buyers of every sect’. Unusually for a Victorian novelist, he regarded London’s multiculturalism as an asset to be prized.

Petticoat Lane, 2015.

Zangwill also broke new ground in depicting the diversity of contemporary Jewish life. Although it would have been easier to advocate for Jewish immigrants by representing them as a cohesive community with shared needs and aspirations, he instead drew the novel’s dramatic scenes from the conflicts of class, religion and generation that fissured it. He intended, he wrote, ‘to exhibit clearly that the Jew, like the Englishman, cannot be summed up in any single, or indeed in any score, of types’. Children of the Ghetto explores divisions among Jews who are wealthy and poor, orthodox and secular, immigrant and English-born, men and women, parents and children. This was a fractured, deracinated population – uncertain of its future, at a moment of critical change.

It’s this complexity that I want to convey in Zangwill’s Spitalfields, a smartphone app that uses Children of the Ghetto as the basis for a walking tour of the Spitalfields area. The app brings to life the dilemmas that beset immigrants and their children in the context of fierce debates about migration from more than a century ago. Like the novel, the app’s narrative follows the story of Esther, a London-born ‘grandchild of the ghetto’, her routes between soup kitchen and school, attic home and marketplace and her changing relationship to Spitalfields. Many of the sites where Zangwill stages the novel’s key scenes are still extant, offering a series of physical settings where the app augments extracts from the novel with related visual and aural materials from the period. And I’m able to use the unique capacity of mobile digital technology to immerse the listener in Spitalfields’ past while remaining attentive, or becoming more attentive, to its present, as you walk through a streetscape shaped by more recent histories of migration.

Perhaps the most remarkable fact about Children of the Ghetto is that it became a bestseller following its publication and was repeatedly reprinted for several decades. Written in the context of widespread confusion about immigration, the novel opened up a little-known world to the reading public. But Victorian readers found more than novelty in its pages: they also encountered the story of a daughter rebelling against her father’s authority, a father striving to understand his son’s lack of interest in his family’s traditions, a woman longing for the warmth and security of her childhood home. Readers discovered that the struggles of Jewish immigrants in Victorian London were not so different from their own.

Nadia Valman is Reader in English Literature at Queen Mary, University of London. She researches and teaches the literature of east London, where she also leads guided walks. She wrote and curated the free downloadable smartphone app Zangwill’s Spitalfields.

6 November, 2015

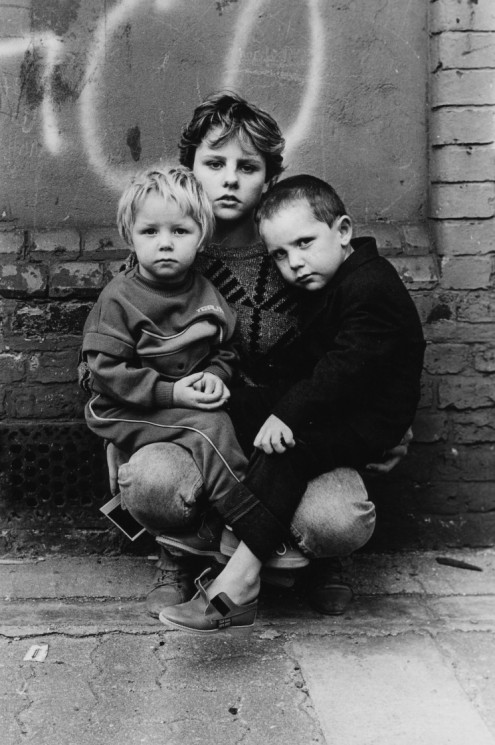

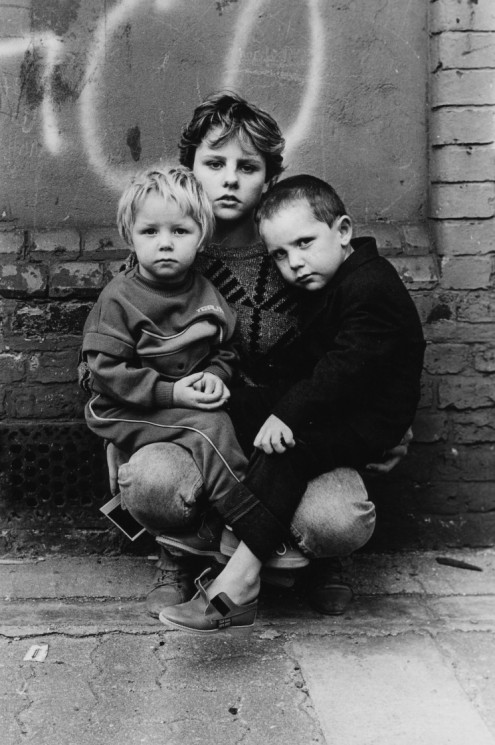

A weird coincidence occurs shortly after Colin O’Brien and I sit down for a coffee in Hackney PictureHouse, just across the road from where his photos formed part of the Migration Museum Museum’s first exhibition of 100 Images of Migration at Hackney Museum. A young man, George Nelson, sits down at our table and, spying the books Colin has laid out in front of us, apologises for intruding on our conversation – but he has to show us the image he has open on his phone. It’s the front cover of Colin’s book, Travellers’ Children in London Fields, which George (a photographer himself, it emerges) has just been recommending to a contact. There follows a conversation in which George expresses his admiration for Colin’s work, and Colin, generous and courteous as ever, asks questions about George’s work. Throughout it all, Colin seems completely unfazed by the coincidence or the praise, making no big deal about either.

The cover photo for Colin’s “Travellers’ Children in London Fields”, 1987 – ‘I took many pictures over a period of three weeks and they took me into their confidence. It was only when I started to print the images that I realised what an amazing set of photographs they were.’

Making no big deal about it is not a bad way of summing up Colin’s approach to his work. He’s certainly made no big deal about it in terms of money, though he is entirely without bitterness on that account. ‘When I was starting out,’ he says, ‘there were two routes open to you if you wanted to make it big as a photographer. You could become a war photographer, as Don McCullin did, but I was too scared to do that; or you could do a David Bailey and become a celebrity photographer – but I just wasn’t interested in that world.’ In fact, Colin never became a photographer as such, not in the professional sense. All his photography was done in the margins of his working life, which was spent as a media resources technician for the ILEA and the GLC, and at the London College of Printing. For two hours or so every day, though, he would walk the streets with his camera, taking photographs of people who interested him.

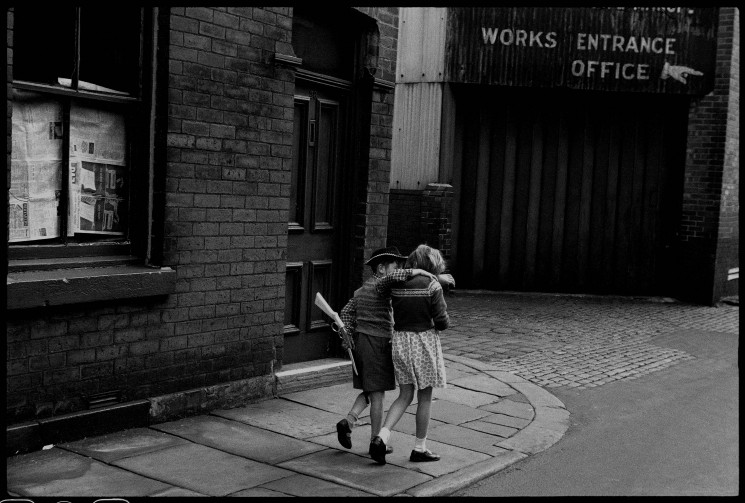

Cowboy and Girlfriend, Bolton, 1960 – ’Because I kept very bad records in the old days I thought that the picture had been taken in London, but a very nice lady wrote to me and told me that it was taken in Bolton. She named the very street, long since been demolished – she said Bolton was now a mess! It has probably been one of my most liked images.‘

He’s been taking photographs almost all his life. His Uncle Will gave him a box camera when Colin was eight years old (one of the photographs he took with this camera is in 100 Images: ‘Raymond Scallione and Joe Bacuzzi’, two boys posing with Italian magnificence on the bonnet of a black Ford in 1948), he had a Leica at the age of 14, has had more than 30 exhibitions in the course of his lifetime and is still – now well into his 70s – taking photos, both digital and film, and processing and printing his work in the traditional way in a darkroom.

Hatton Garden, 1948 – ‘Raymond Scallione and his friend, Joe Bacuzzi, pose for me in this photograph taken when I was eight years old.’

In theory he’s retired but he has provided the photographs to more than 50 of the famous Spitalfields Life blog, he has just completed a new exhibition called London Life (beautifully recreated in a book published by Spitalfields Life and available on their site) and he has a new project lined up, on West End life, which he is undertaking with a young photographer, Alex Pink. You get the impression that Colin is not putting the lens cap back on his camera any day soon.

Burgess Park Lake, Old Kent Road, 1984 – ‘I’d photographed these girls before. They sat on a bench beside this man who had been following them around and, when I raised my camera again, each of them pulled a funny face and poked their tongues out.’

Brief snippets of his life emerge in the course of our talk. Although he has no trace of an Irish accent (apparently one emerged somewhat unexpectedly, and to the great amusement of his friends, in the course of an interview on the Robert Elms radio show), he is proud to describe himself as of Irish extraction, his grandparents having moved to England from Ireland in the late 19th century. His childhood was spent in London during what he calls the ‘threadbare years’, the last years of the war and the half-decade that followed. His adolescence was mostly playing football in the park with an impressive roster of future writers (Bill Naughton, Frederic Raphael and Brian Glanville among them), and he celebrated narrowly missing out on national service by ‘bumming around’ in his 20s. He had the opportunity to photograph the Beatles before they were famous (he used to take photographs for Dick James, the music publisher who took over Northern Songs) but turned it down, because he was too busy – or maybe, I wonder, because he had a foretaste of their future fame, and wasn’t interested. And all the time he was doing what inspired him, the real job his 9 to 5 job allowed him the time and space to do (when he wasn’t studying for a degree and a masters): taking pictures on the streets of London, capturing the passing scene of an ever-changing city.

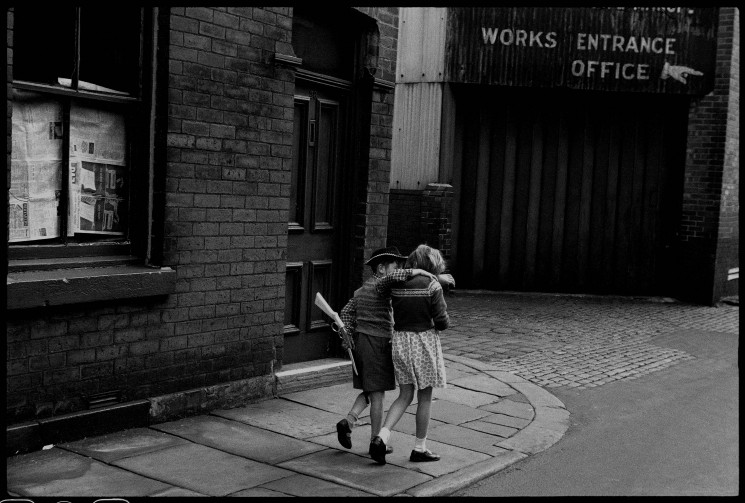

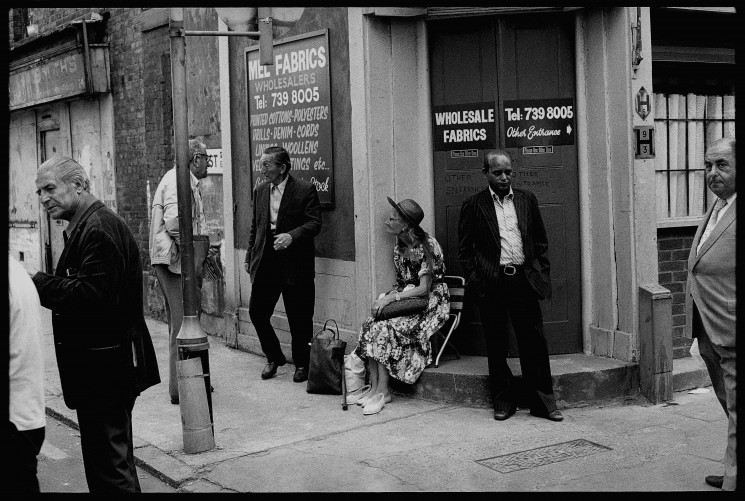

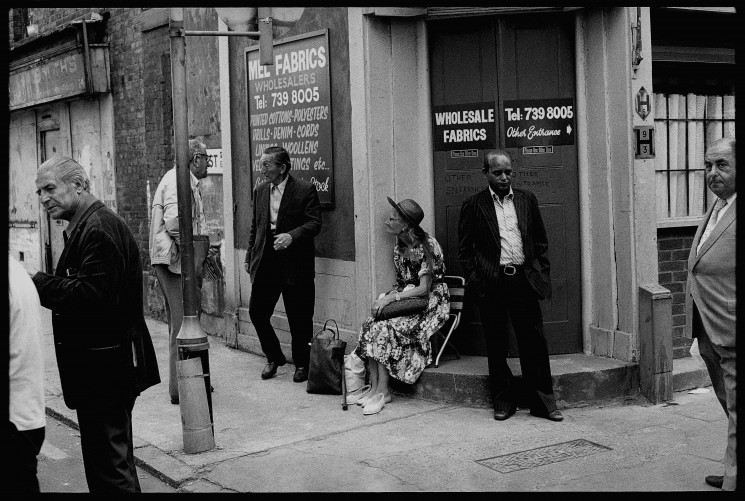

Comings and Goings, 1986 – Corner of Bacon Street and Brick Lane, Spitalfields

It’s clearly not the money that motivates him. Most of his exhibitions and publications he has paid for himself. And he’s not, as we’ve seen, interested in fame. His photography is an act of kinship similar to his involvement in community projects and campaigns such as the fight to save the Marquis of Lansdowne or the attempt to prevent the development of Norton Folgate. Something similar motivates him to continue taking his camera out on the street – an insatiable curiosity for, and an empathetic engagement in, other people’s lives. I’m guessing here, because this grandiose kind of phrase isn’t likely to be what Colin would say. His account would be something along the lines of ‘I just like people’, and maybe it is just that. Certainly there appears to be no distance, literally and metaphorically, between Colin and his subjects: his photos are imbued with a rare warmth and generosity.

Wandsworth, 1973 – ‘These boys knew how to make good use of old pram wheels!’

Ah yes, that generosity. The books he’s brought with him are for me – an act of unassuming kindness on his part that touches me deeply. When I am flicking through the books later, making notes for this blog and trying to work out why his images have such emotional heft, it is this I come back to: his generosity, his engagement in other people’s lives, his sense that nothing divides us – we are all in this together.

Junction of Clerkenwell Road and Farringdon Road, 11 June 1962 – ‘I read later that a child died in this accident. There was a rumour that the traffic lights malfunctioned, and all turned green at the same time.’

Colin O’Brien’s photos can be viewed on his website, colinobrien.co.uk. His latest book, London Life, is published by Spitalfields Life Books and is available from all good bookstores and on the Spitalfields Life site.