18 October, 2017

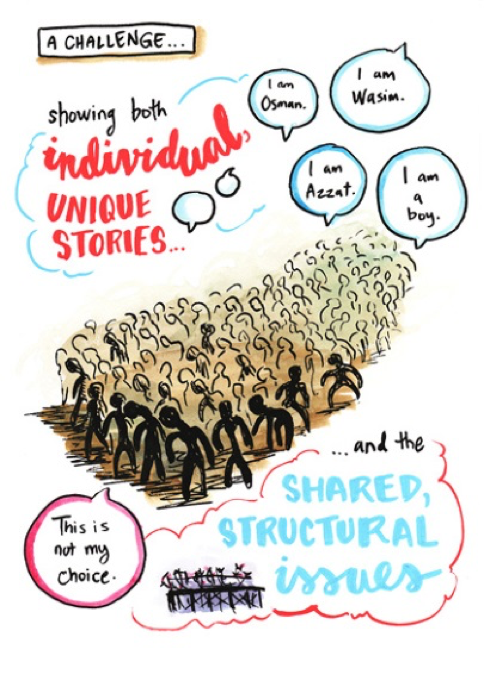

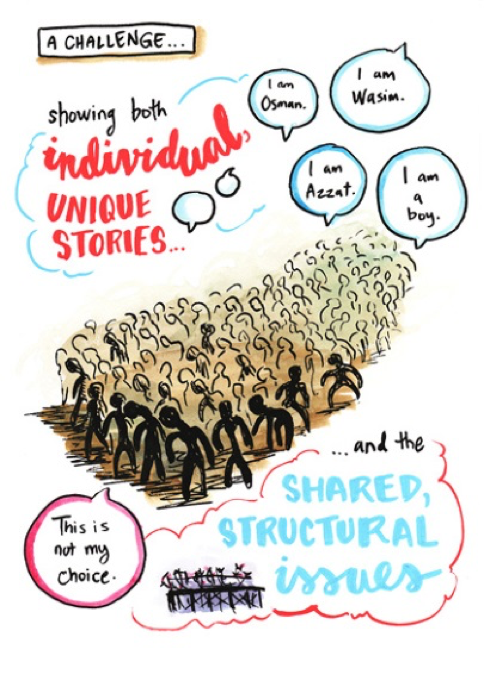

In the second of three blogs on holding workshops with school pupils on the issues of migration, Umut Erel and Elizabeth Newcombe discuss an attempt to introduce pupils to the complexities of the language and the policy issues surrounding immigration, at a time of great global inequality and economic recession.

When holding a workshop for a school from Sussex at the Migration Museum Project’s Call Me By My Name exhibition in July 2017, it was striking to see school pupils becoming passionately engaged with issues of migration. The group of 15 pupils and their teachers arrived on one of the hottest days of the year, having already spent time wandering through London. Emily Miller, MMP’s head of learning and partnerships, started the workshop with an interactive game, using questions and movement in the space of the museum to break the ice and find out how everyone relates to migration. Some of the questions she asked were:

- Do you know someone who has migrated?

- Do you speak more than one language?

- Has anyone in your family migrated?

If our answer to these questions was ‘yes’, we had to take a step forward; if the answer was ‘no’, we were asked to take a step backwards. Soon most of us were concentrated in a tight circle in the middle of the room, and it had become clear that there was a lot of experience of migration, whether personal or indirect.

Drawing by Laura Sorvala.

The workshop then moved on to look at some of the key terms in the migration debate. A young refugee told of his experiences of migration, finding his way around life in the UK and how he now works in arts and education organisations in which he initiates dialogues on the experiences of refugees and migrants. All of us were stunned to hear of the difficulties he had overcome on his journey to the UK in the early 2000s. Some of the pupils shared their personal experiences of the country he came from and the countries he had passed through, which gave the encounter added poignancy.

After this informative and emotionally charged part of the workshop, we changed gears slightly and introduced a more academic take on the issues. Starting with an interactive exercise on global inequalities of income, we began to question the term migrant, pointing out that, when we use the terms ‘migrant’ and ‘refugee’, this does not refer to a legal figure or a dataset, but to a political figure. We discussed how British people living abroad almost always think of themselves as ‘expats’ not ‘migrants’, while Black Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) people who were born and have lived all their lives in the UK are often called ‘second generation migrants’. So, the decision about who counts as a migrant is often framed by assumptions about race, class and nationality.

When discussing migration, we often hear about the need to protect the welfare state from outsiders, but how can we understand the welfare state against the backdrop of global inequalities? We are living at a time of the highest level of global inequality in human history, when the wealth of 67 people is the same as the combined total of the world’s 3.5 billion poorest people, and the poorest 50 per cent of the world have 6.6 per cent of total global income. There are issues with the methodology of these estimates, but it cannot be denied that the world has changed from the 19th century. Today, for most people in the world, what is key to your life chances is the country you live in. The fear for those living in wealthier states is that there are a lot of people who are hard up in the world and that, if you don’t have much, you need to hold on to it.

Photo of the PASAR project’s ‘From Margins to Centre Stage’ workshop, February 2017 © Marcia Chandra.

Migrant families’ exclusion from the welfare state was a topic in another research project – Participation Arts and Social Action in Research (PASAR) – we are currently running with our colleagues Erene Kaptani (Open University), Maggie O’Neill (University of York) and Tracey Reynolds (University of Greenwich). The PASAR project conducted participatory research with migrant mothers affected by the policy No Recourse to Public Funding (NRPF), which means migrants who are subject to immigration control are not allowed to access benefits, tax credits or housing assistance. This policy affects both migrants who have the right to remain in the UK and those who are undocumented. The policy pushes these migrant families – many of whom include young children, who are among the most vulnerable people – to the margins of society through poverty and racism. In a workshop with policy makers, practitioners and activists, we worked with a group of migrant mothers affected by NRPF to enable their collective voice to be heard. To do so, we showed a short theatre piece developed through the research.

Photo from PASAR project theatre scene © Marcia Chandra.

At the schools’ workshop, we watched a short scene from this theatre piece about Elaine’s experience. Elaine had been working for many years for a large supermarket. She needed to take time off every two weeks to sign into the Immigration Reporting Centre, a requirement of the Home Office. Her manager used his knowledge of her vulnerability to bully her and change her onto an unfavourable night shift, even though she had just had a baby. Her union representative’s response was that as an immigrant she should be glad to have a job. She also experienced stigmatisation by fellow workers, who saw her as an ‘illegal’ immigrant. Eventually, she lost her job – unable to pay rent, Elaine, her husband and six-year-old son have for four years now been living in the houses of friends and acquaintances, surviving on their monetary support.

This example shows how racism, anti-immigration policies and austerity intersect. An increasingly hostile climate to immigration has made it more difficult for migrants to find formal and informal employment. As a consequence of increasingly stringent migration regulations, particularly since 2012, more and more migrant families are subject to migration control, prevented from accessing public funds and rendered unable to economically support themselves (Price and Spencer, 2015). In a situation of crisis – through the loss of jobs or accommodation, relationship breakdown or health problems – they cannot draw on the relative safety net of the welfare state to help them overcome these points of crisis and are pushed more and more to the margins of society.

Having watched a short video clip of these theatre scenes with the school pupils, we had an interesting discussion about some of the issues raised by Elaine’s story:

- How can labels such as ‘illegal migrant’ be misleading and stigmatising?

- Why are some people, and not others, allowed to draw on welfare services?

- Should contributions through work be the criterion for deciding whether migrants can participate in the welfare state?

- Should there be other criteria for inclusion into welfare, based on colonial and postcolonial ties?

- Should there be criteria based on shared humanity?

It is hard to summarise the workshop, as it was rich and varied, but it seems to me that this variety of modes of engagement (personal testimony, interactive activities, and audio-visual material and information) has been fruitful in raising many questions, showing the complexity of issues of migration and welfare, and linking conceptual discussions to personal experiences of migration, which are often far richer than those portrayed in public debate. While teachers challenged us as academics to present information in accessible ways, especially for pupils who are still learning English, their feedback was heartening: ‘Our students learnt a lot from the experience both about migration at the human level but also the bigger picture of why these issues are so pressing for the UK at the present time. A great day well spent!’

Reference

Price, Jonathan, and Spencer, Sarah (2015) Safeguarding Children from Destitution: Local Authority Responses to Families with ‘No Recourse to Public Funding’. Oxford: COMPAS.

Umut Erel is Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the Open University. She is Principal Investigator of PASAR, an ESRC-funded research project investigating the opportunities and challenges of using participatory theatre and walking methods for social research.

Emma Newcombe is the Head of External Relations for COMPAS and the Global Exchange on Migration and Diversity. She oversees all COMPAS’s communications work, and also supports the development of the ESRC Urban Transformations project. She has an MA in Migration Studies from the University of Sussex and a BSc in Social Policy from the University of Bristol.

6 October, 2016

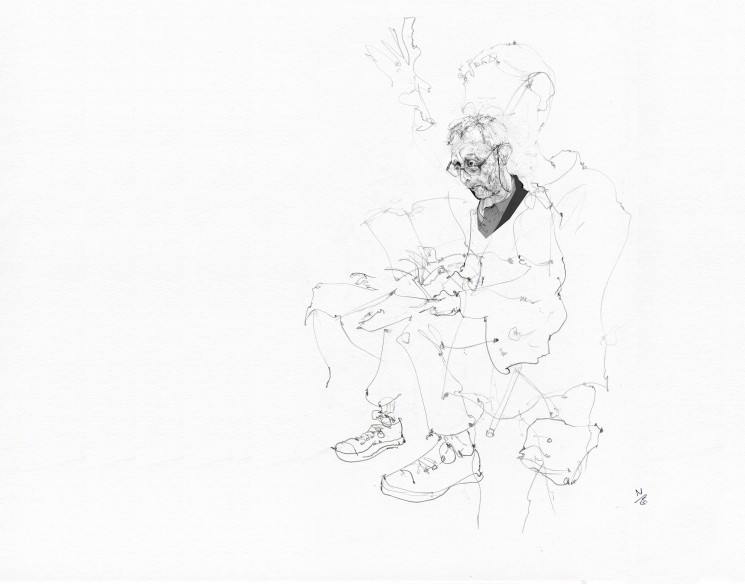

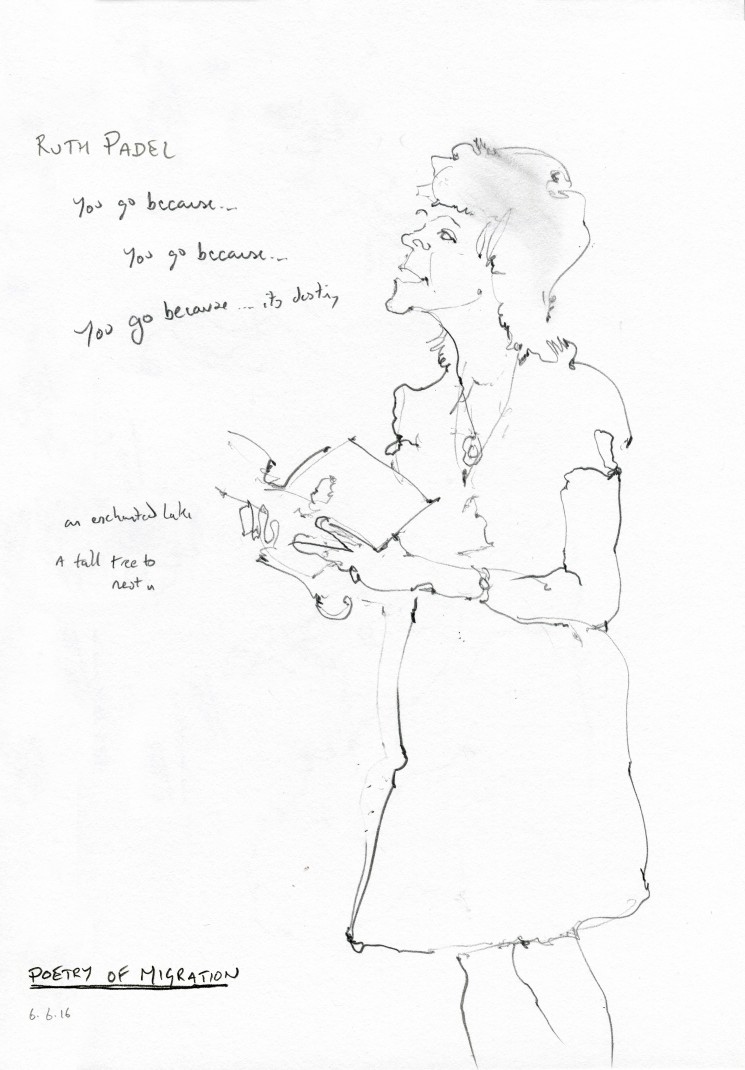

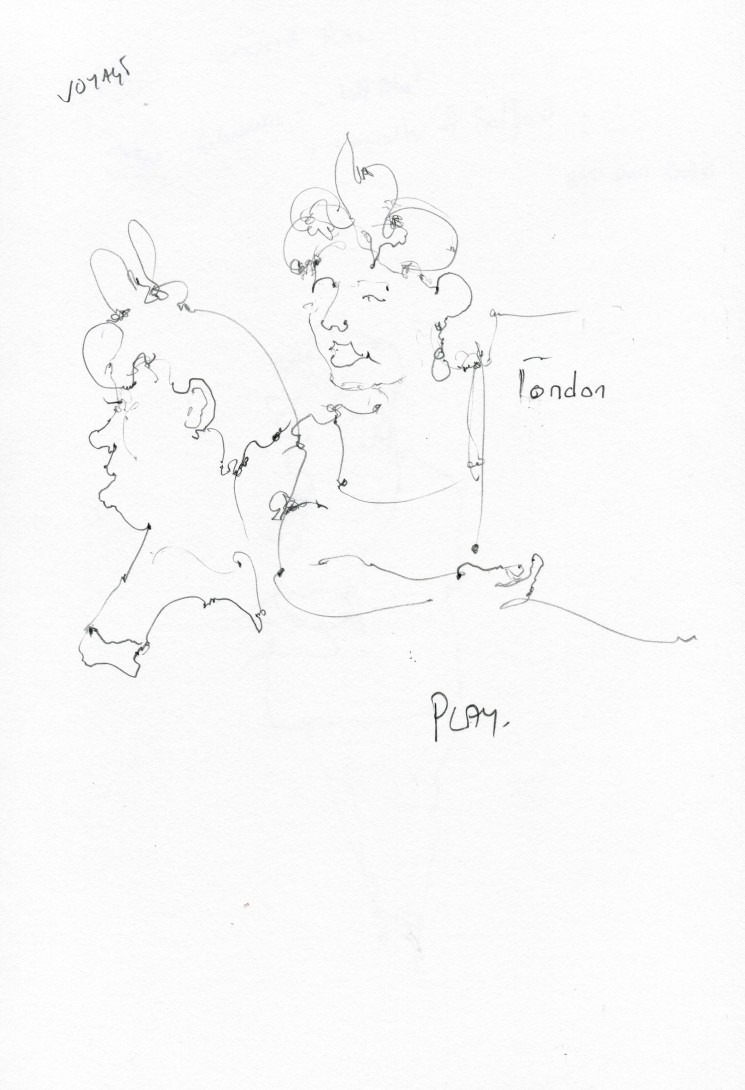

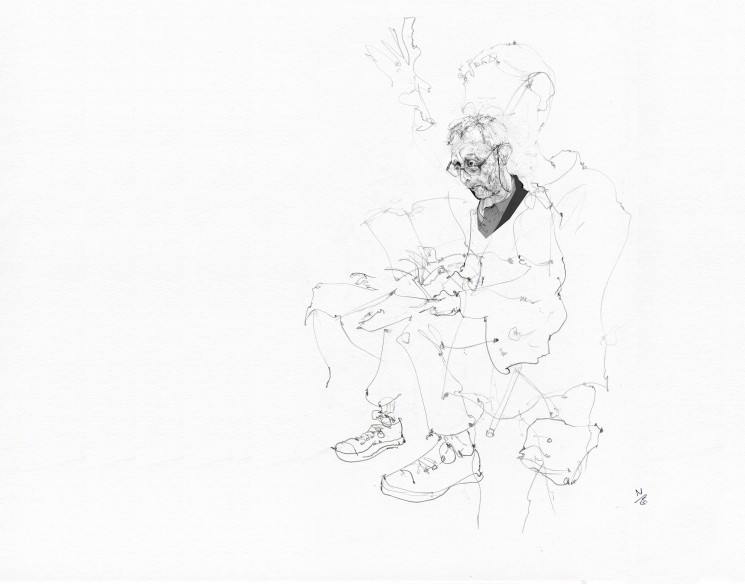

Michael Rosen, compering the ‘Poetry of Migration’ event at Londonewcastle Project Space earlier this year; drawing by Nick Ellwood.

One of the first events we held in the course of our three-week residency at Londonewcastle this summer (where more than 4,000 people visited our exhibition Call Me By My Name: Stories from Calais and Beyond) was the ‘Poetry of Migration’ on Tuesday 6 June. Michael Rosen (distinguished poet, writer, entertainer – and distinguished friend of the Migration Museum Project) compered the event, at which Ruth Padel and Jackie Kay were fellow guest speakers.

When we’d advertised the event, we had also asked people to let us know if they would like to present their own poems, so the evening was less about studious, respectful listening to the panel poets – though it was that, too – and more about participation. People presented their poems from the floor – Sophie Herxheimer, PJ Samuels, Antoine Cassar, Nadia Faydh and Elizabeth-Jane Burnett among them – and the audience expressed the full range of response you might have expected from an evening of poetry based around the theme of migration: tears, laughter, some anger, some despair. As a curtain-raiser for the exhibition itself, it was perfectly judged.

Nick Ellwood, the artist behind the panel drawings of Jungle residents in the middle room, sat in the audience and drew portraits of some of the performers. We’ve reproduced his drawings in this blog, together with some of the poems read out by the people he was drawing. It’s a rich combination: one of the artists we were privileged to work with for the exhibition producing beautiful sketch drawings of some of the incredibly talented writers we were thrilled to have perform at the event. We hope you enjoy this memento of the evening.

Ruth Padel

Purple Ink

She has waited three years for this. Too ashamed

to even half-tell the young woman in spectacles

tapping a purple biro on a desk

exactly what the soldiers did to her, each versatile

in his turn, she gets wrong Date your mother was born

and sees a stamp the colour of desert night descend on her file.

The Prayer Labyrinth

She went looking for her daughter. How many

visit Hades and live? Your only hope

is the long labyrinth of Visa Application

interviews with a volunteer from a charity

you’re not allowed to meet. You’ve been caught:

by a knock on the door at dawn

or hiding in a truck of toilet tissue

or just getting stuck in a turn-stile.

You’re on Dead Island: the Detention Centre.

The Russian refugees who leaped from the fifteenth floor

of a Glasgow tower block to the Red Road

Springburn – Serge, Tatiana and their son,

who when the Immigration officers

were at the door, tied themselves together

before they jumped – knew what was coming.

Anyway you’re here. Evidence of cigarette

burns all over your body has been dismissed

by the latest technology. You’re dragged

from your room, denied medication

or a voice. You can’t see your children,

they’re behind bars somewhere else.

You go on hunger strike. You’re locked

in a corridor for three days without water

then handcuffed through the biopsy

on your right breast. You’ve no choice

but to pray; and to walk the never-ending path

of meditation on not yet. Your nightmare

was home-grown; you’re seeking sanctuary.

They say you don’t belong. They give you

a broken finger, a punctured lung.

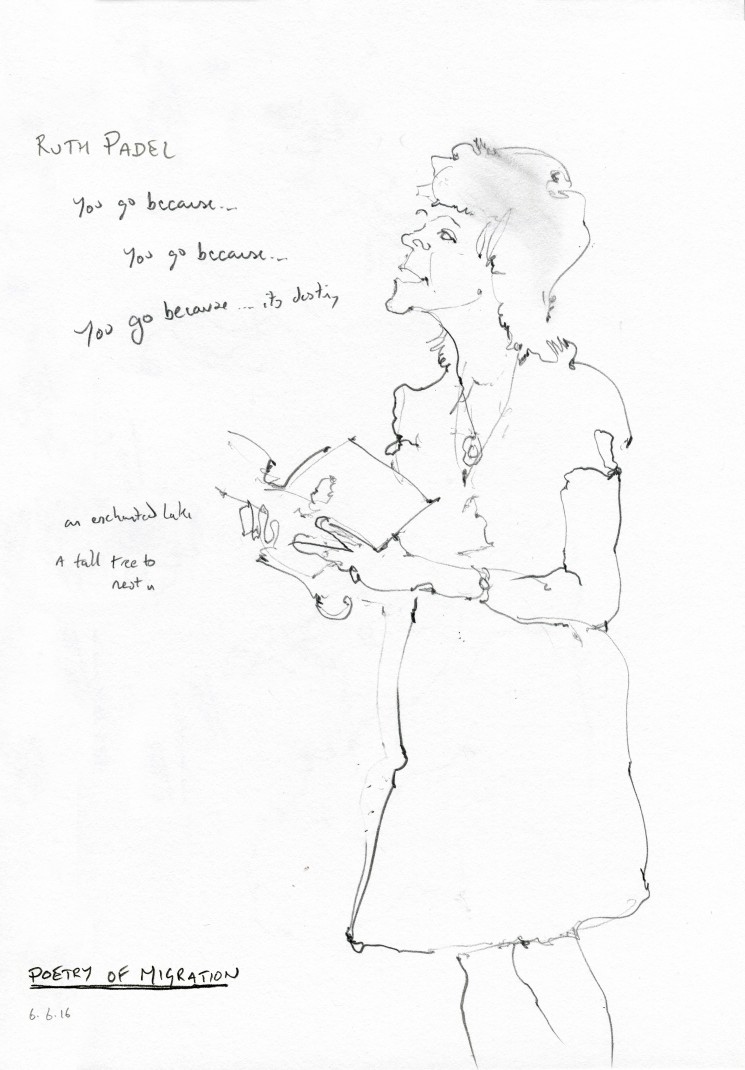

Ruth Padel, reading her poem ‘Time to Fly’; drawing by Nick Ellwood.

Time to Fly

You go because you heard a cuckoo call. You go because

you’ve met someone, you made a vow, there are no more

grasshoppers. You go because the cold is coming, spring

is coming, soldiers are coming: plague, flood, an ice age,

a new religion, a new idea. You go because the world rotates,

because the world is changing and you’ve lost the key.

You go because you have the kingdom of heaven in your heart.

And the kingdom of hell has taken over someone else’s heart.

You go because you have magnetite in your brain, thorax, tips

of your teeth. Because there’s food over the hill

and there’ll be gold, or more likely bauxite,

inside the hill. You go because your mother is dying

and only you can bring her the apples of the Hesperides.

You go because you need work.

You go because astrologers say so. Because the sea

is calling and your best friend bought a motorbike

in America last year. You go because the streets are paved

with gold and your father went when he was your age.

You go because you have seventeen children and the Lord will provide;

because your sixteen brothers have parcelled up the land

and there’s none left for you. You go because the waters are rising,

an ice sheet is melting, the rivers are dry

there are no more fish in the sea. You go because God

has given you a sign – you had a dream – the potatoes are blighted.

Because it is too hot, too cold, you are on a quest for knowledge

and knowledge is always beyond. You go because it’s destiny,

because Pharoah won’t let you light candles at sundown on Friday.

Because you’re looking for

an enchanted lake, the meaning of life, a tall tree to nest in.

You go because travel is holy, because your body

is wired to go, you’d have a quite different body and different brain

if you were the sort of bird that stayed. You go

because you can’t pay the rent: creditors lie in wait for your children

after school. You go because Pharoah has hogged the oil,

electricity and paraffin so all you have on your table

are candles, when you can get them.

You go because there’s nothing left to hope for;

because there’s everything to hope for and all life is risk.

You go because someone put the evil eye on you

and barometric pressure is dropping. You go because

you can’t cope with your gift – other people can’t cope with your gift –

you have no gift and the barbarians are after you.

You go because the barbarians are gone, Herod

has turned off the internet and mobile phones, the modem

is useless and the eagles are coming. You go because the eagles

have died off with the vultures and the ancestors are angry

there’s no one to clean the bones. You go in peace, you go in war.

Someone has offered you a job. You go because your dog

is going too. Because the Grand Vizier sent paramilitaries to your house last night

you have to go quick and leave the dog behind.

You go because you’ve eaten the dog and that’s it, there’s nothing else.

You go because you’ve given up and might as well. Because your love

is dead – because she laughed at you; because she’s coming with you,

it will be a big adventure and you’ll live happily ever after.

You go in hope, in faith, in haste, high spirits, deep sorrow, deep

snow, deep shit and without question.

You pause halfway to stoke up on Omega 3 and horseshoe crabs.

You go for phosphorus, myrtle-berries, salt. You go for oil

and pepper. It was your father’s dying wish.

You go from pole to pole, you go because you can,

you have no feet, you sleep and mate on the wing.

Because you need a place to shed your skin

in safety. You go with a thousand questions but you are growing up,

growing old, moving on. Say goodbye to the might-have-beens –

you can’t step into the same river twice.

You go because hope, need and escape

are names for the same god. You go because life

is sweet, life is cheap, life is flux

and you can’t take it with you. You go because you’re alive,

because you’re dying, maybe dead already. You go because you must.

© Ruth Padel from The Mara Crossing, Chatto and Windus, 2012

Sophie Herxheimer

London

Not zo mainy Dais zinz ve arrivink.

Zis grey iss like Bearlin, zis same grey Day

ve hef. Zis norzern Vezzer, oont ze demp Street.

A biet off Rain voant hurt, vill help ze Treez

on zis Hempstet Heese vee see in Fekt.

Vy shootd I mind zat?

I try viz ze Busses, Herr Kondooktor eskink

me … for vot? I don’t eckzectly remempber;

Fess plees? To him, my Penny I hent ofa –

He notdz viz a keint Smile – Fanks Luv!

He sez. Oh! I em his Luff – turns Hentell

on Machine, out kurls a Tikett.

Zis is ven I know zat here to settle iss OK. Zis

City vill be Home, verr eefen on ze Buss is Luff.

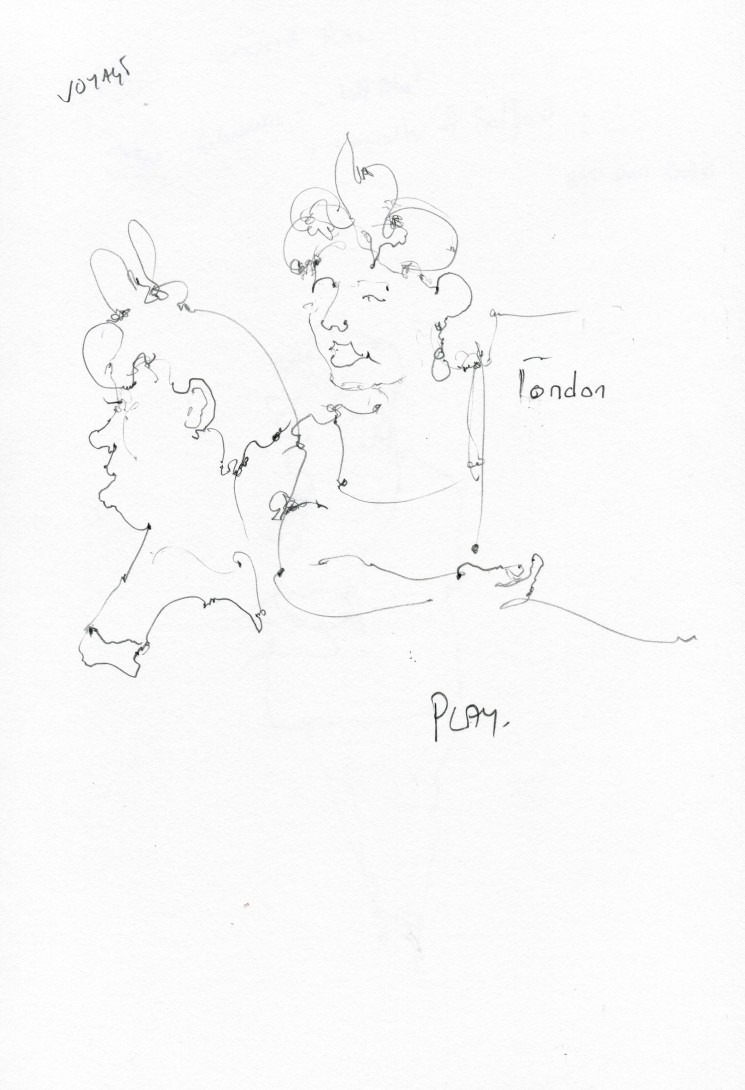

Sophie Herxheimer, drawn in full flow when reading ‘London’; drawing by Nick Ellwood.

Vosch by Hendt, Lern by Hart!

Ze yunkest off my grayt grayt

Grent-Childtrenn is lynink up

her Dollse oont Behrs for Klarse.

Ven zay slump in rekggitt

Exhorstschon, she arraintches zem

to lean on ze Kupboart. Zit up ztrate!

She Kommarnts. If Enny Vun

off you nose ze Aanser, don’t

schout out; poot up your Hendt!

Ze Svetter zat zis Teacher

vairs, looks ottley familiar.

Ze Vun Aunt Frieda sent from Vienna

for my Girl ven she voz small.

I see ze Vool still hess some Bountz.

Oont amazinkly, no Moss Holse!

Funny Frieda alvays sett she dittn’t

leik to knit: I heffnt ze Payschunz,

she leidt. Zis Svetter hess en intrikett

Pettern off blue Skvairs, raist in a Ridch

ofa nice veit Stokkink Stitch –

I marfellt et it zen, ven it arrifte, springink

like a Lemm from stiff brown Paper.

Vizzin Veeks of zat, Frieda, leik zo Menny,

voz seeztd, imprissont, murdtert.

Now zis endurink Laybor off hurze

iss vorn ess a Keint off Uniform:

kommarntink All who are born, or eefen

stufft: Make Sinks. Make Sinks up! Play!

© Sophie Herxheimer

‘London’ first appeared as no.22 in a series of concrete poetry broadsides from Brazil, called POW, subsequently appearing in Jewish Quarterly and Long Poem Magazine, and was also made into a film.

‘Vosch by Hendt, Learn by Hart’ has just been published in the Vanguard Anthology.

Nadia Faydh

Things I miss

When I wake up to the cloudy sky

Of London,

I feel overwhelmed:

A fit of yearning.

It is not that I want to go back,

but simply miss the way it was:

The sunny mornings,

The fresh smell of Cardamom

My mother used to make with tea

Or the smell of fresh bread,

When my father is back from the bakery …

Maybe I miss those Fridays,

When all the sisters gather around;

Voices of playing kids

Filling the air with delicious noise,

“the house can’t take us all,”

I would say,

My mother would stop me…

She likes it when we’re all there.

Maybe I miss dad’s big smile:

when his granddaughters

Greet him with a kiss.

I miss watching all the girls

Working in the kitchen,

Or Sit to the table laughing loud …

Dad would come in, take a picture,

To remember those moments I miss!

© Nadia Faydh

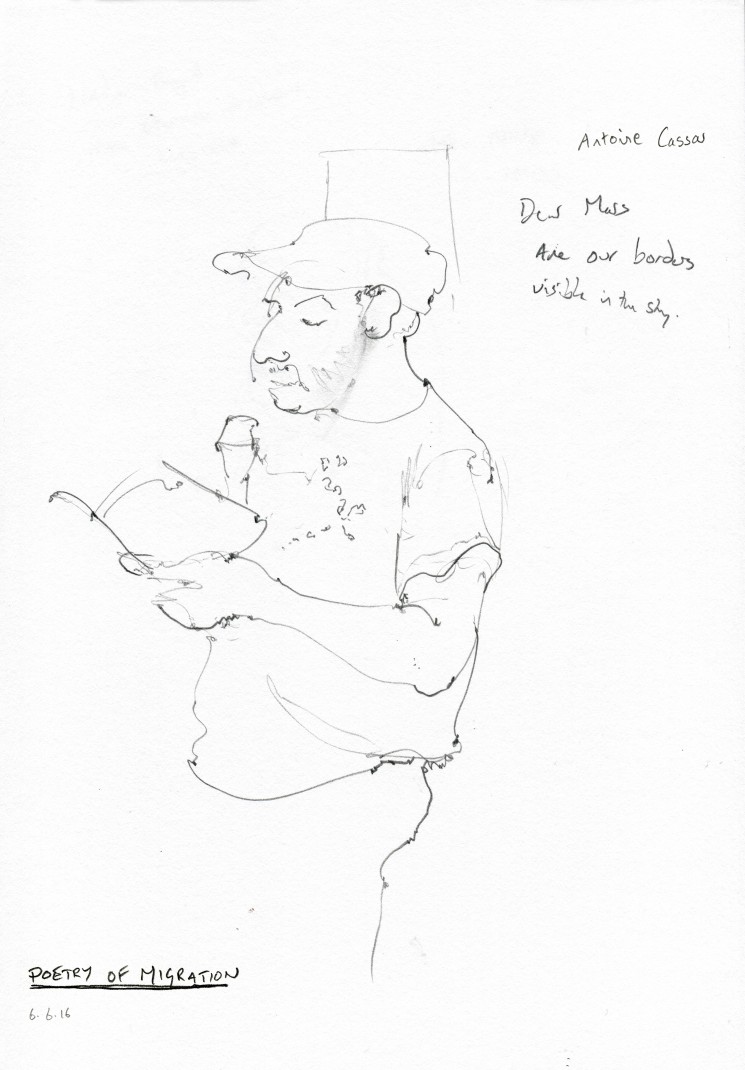

Guest readers at the event – Antoine Cassar on the left, Nadia Faydh on the right; drawing by Nick Ellwood.

Antoine Cassar

8 ħajki bla fruntieri

8 no-border haiku

1

L-ajruport. Tifel

ċkejken jaqbeż iċ-checkpoint.

Ma jafx b’fruntieri.

The airport. Boy leaps

over the customs checkpoint.

He knows no borders.

2

Tfajjel Sirjan

fuq il-kanvas tat-tinda

ipinġi d-djar.

A Syrian boy

paints houses on the canvas

of his tent.

Antoine Cassar, drawn by Nick Ellwood.

3

L-ebda bandiera

ma jistħoqqilha qima

daqs l-id li tħitha.

No flag, large or small,

deserves greater esteem than

the hand that sews it.

4

Il-bnedmin jaqsmu

l-fruntieri? Anzi. Il-fruntieri

jaqsmu ’l-bnedmin.

People cross borders.

It’s been that way ever since

borders crossed people.

5

Għeżież nies ta’ Mars:

jidhru l-fruntieri tagħna

fis-sema tagħkom?

Dear people of Mars:

are our borders visible

in your evening sky?

6

Ewropa! Intix

tisma’ l-imħabba ssejjaħ

minn qiegħ il-baħar?

Europe! Can you not

hear love calling out from the

bottom of the sea?

7

Għidli ftit, baħar,

kif għadek tmelles l-art

li tridek qabar?

Would you tell me, sea,

why you still caress the land

that has made you a grave?

8

Id-dinja tonda?

Saqsi lir-riħ, u ‘l-fens

mal-art ta’ Calais …

Is the world not round?

Ask the wind. Ask the Calais

fence, blown to the ground d…

Elizabeth-Jane Burnett

Elizabeth-Jane Burnett, drawn by Nick Ellwood.

Talking to Ariel about Our Place in the Canon and Other Sea-Nymph Stuff

What did you notice, apart from the cold?

“It was –4 and three inches of snow.”1

What words will you choose to speak for you, whose

archive to bootleg to send over To:

recipients of black body unable to process except as appropriation or lost thing searching for warm amputations please

find history attached

in a speech of the eyes which do not lie or sound

as a Dali sequence of cuts let us process each other

through peel of vitreous fluid let us touch another fathom falls

as we see what we are made of: these yellow sands, these light bones

pulse as snowdrops through the dead days of autopsy:

still no sea-change.

1 Sam King, aged 81, a migrant from Priestmans River, Jamaica, to Bexley, Kent.

PJ Samuels

PJ Samuels, drawn by Nick Ellwood.

Whittle

I didn’t come here under a lorry

with bin liners over my head

so the carbon dioxide readers

cannot sense my breath

I didn’t sail here on a rubber dingy

and watch my brothers and sisters

become food for sea creatures

I didn’t cross a continent over land

needing to buy a new passport

and acquire a new name

at each border crossing

I am from Jamaica

Called the pearl of the Caribbean Sea

It is beautifully idyllic

My land is not torn apart by war

Just chained by terminal culture norms

I was on last rites

I bought a ticket, flew British Airways

Was served vodka and lemon en flight

Here I am

Tell me your story you said

Here is the altar, worship I brought me

And you made of me a sacrifice

Systematically stripped me

Peeled back my flesh

and pulverized my bones

Whittled me down to who I fuck

To how I fuck

To when I learned what fuck was

To how many times did you fuck her

what exactly did you do

Torn apart by need

whittled

Whittle

To cut small bits or pare shavings from

To reduce or eliminate gradually

To cut or shape wood with a knife.

Not a word much used

to describe a human being

But in your eyes, am I human?

You taught me inconsequential.

I brought the best of me

and had to learn that what you really wanted

was no part of me

With your callused carpenter’s hands

you whittled me down

to what you find consumable

there, you said,

I have made you beautiful

See how good I am to you?

here I am

your Pygmalion

your Aphrodite’s blessing

your social experiment

your triumph

Don’t I wear your guilty well?

Always with the dichotomy

of gratitude and grief

Wracked by survivors’ guilt

I sorrow for fragments of me left

in a land across waters

But it’s the pieces you took that remade me warrior

A constant itch under skin

I sit on the fence

vacillating between thank you and fuck you

And knowing even so

I am one of the lucky ones

Michael Rosen

Madame le Pen

Mme Le Pen,

la raison pourquoi

on a donné une étoile jaune

à l’oncle et à la tante de mon père

la raison pourquoi

on a demand qu’ils devaient attacher

une affiche disante ‘Enterprise juive’

à leur étal de marché

la raison pourquoi

ils ont fuit leur asile

dans la rue Mellaise à Niort

la raison pourquoi

ils se sont réfugiés à Nice

la raison pourquoi

on les a arrêtés et on les a transportés

à Paris, à Drancy, à Auschwitz et à leurs morts

est parce que

les officiers de Vichy

ont fait un ‘Fishier juif’ des juifs étrangers

et l’a donné aux Nazis au moment exacte

que la Résistance a dit bienvenu aux juifs

bienvenu aux étrangers

et c’est ça, la raison pourquoi

je vous dis ces choses

Mme Le Pen.

Michael Rosen, reciting his poem ‘To Madame le Pen�’; drawing by Nick Ellwood.

Mme Le Pen,

the reason why

they gave a yellow star

to my father’s uncle and aunt

the reason why

they told them they had to fix a sign

saying ‘Jewish Business’ on their market stall

the reason why

they fled from their refuge in the rue Mellaise

in Niort

the reason why

they took refuge in Nice

the reason why

they were arrested and transported

to Paris, to Drancy, to Auschwitz and to their death

is because the officials of Vichy

made a ‘Jewish File’ of foreign Jews

and gave it to the Nazis

at the exact moment

that the Resistance was welcoming

Jews and was welcoming foreigners

and that’s the reason why

I am telling you these things

Mme Le Pen.

Mother Father Cable Street

You Connie Ruby Isakofsky

From Globe Road in Bethnal Green

You Harold Rosen

From Nelson street, Whitechapel

You Connie with your mother and father

From Romania and Poland

You Harold with your family from Poland

You Connie

You Harold

your families working in the rag trade

Hats, caps, jackets and gowns

Hats, caps, jackets and gowns

You both saw Hitler on the Pathe News

You both saw Hitler Blaming the Jews

You both collected for Spain,

collecting for Spain

When Franco came

When round the tenements,

the whisper came

Mosley wants to march

Here, through the East End

So what should it be?

To Trafalgar Square to support Spain:

No pasaran?

Or to Gardiners Corner to support Whitechapel:

They shall not pass.

Round the tenements

The whisper came

Fight here in Whitechapel

The whisper came:

Winning here

We support

Spain there.

These are the streets where we live

These are the streets where we go to school

These are the streets where we work

They shall not pass.

You Connie

You Harold

Went to Gardiner’s Corner

You went to Cable Street

You piled chairs on the barricades

The mounted police charged you

A stranger took you indoors

To escape a beating

And thousands

Hundreds of thousands came here

Fighting Mosley

Supporting Spain

Thinking of Germany

And

Mosley did not pass.

You Connie

You Harold

Said, today the bombs on Guernica in Spain

Tomorrow the bombs on London here.

And you were bombed

the same planes, the same bombs

landing in the same streets

where you had said

they shall not pass

And the bodies

piled up across the world

Million after million after million after million

You Connie, your cousins in Poland

Taken to camps

Wiped out

You Harold, your uncles and aunts in France and Poland

Taken to camps

Wiped out.

But you Connie, my mother

You Harold, my father

You survived

You lived

We were born

We grew

You mother

You father

told us these things

I write these things

And today,

I tell you these things

We remember here together

Thanks to you

And we say:

They shall not pass.

© Michael Rosen

8 June, 2016

This guest blog is written by Rob Pinney, one of the photographers who submitted photos for our exhibition, Call Me By My Name: Stories from Calais and Beyond, which is at 28 Redchurch Road, London, until 22 June (details here). Rob’s book, The Jungle, is on sale at the exhibition and from his website (see below) with all profits going to charities working in Calais.

A complex relationship in a complex place

Grocery Store, November 2015. Shops like this provide, among other things, basic food staples and mobile phone credit top-ups, incredibly important for keeping in touch with family both at home and often at different stages of the refugee ‘trail’ through Europe. Many people in the ‘Jungle’ report having been victimised and attacked by both the police and ordinary citizens when outside the camp, and so feel unsafe walking into Calais to use local shops. This particular shop was destroyed in March 2016 as part of the eviction and demolition of the southern half of the camp. © Rob Pinney

As the main point of departure for sea and rail travel to Britain, the coastal town of Calais in northern France has become a ‘hotspot’ for asylum seekers hoping to build a new life in the United Kingdom.

‘The Jungle’ — the term used to refer to the shanty town settlements that have become synonymous with Calais — has no fixed location. But it is most commonly associated with a former landfill site not far from the ferry port that at its peak during the 2015 refugee crisis held a population of some 8,000 people.

The political discourse around the jungle and those temporarily seeking shelter there thrives on generalisations. Labelled a ‘swarm’ and a ‘bunch of migrants’ by British Prime Minister David Cameron, in the eyes of many the people here are not individuals but a collective mass — the object of a confused war of words: ‘refugees’, ‘asylum seekers’, ‘economic migrants’.

The reality is far more complicated. Many have fled war and political persecution. Others, notably from Afghanistan and Iran, left to avoid being made to fight for a cause they did not believe in. Many will show you photographs on their mobile phones of family already living in the United Kingdom, whom they hope to join. And some have spent years, occasionally decades, living and working in the UK, only to find themselves suddenly ejected. For them, the journey is not one of migration but a return home.

‘What is it like?’, often asked, is a simple question that defies an equally straightforward answer. Unlike the epic photographs of Zaatari in Jordan, whose orderly lines of identical shelters extend outwards on a vast scale, the Jungle follows no such logic. The Jungle is a city. Alongside countless tents and shelters, nestled into any and all available space with little regard to order, stand shops, cafes, restaurants, hairdressers. While different nationalities have generally grouped themselves together — as is common in any city — these lines are also frequently transgressed by a shared political precarity that unites its citizens. But above all, the Jungle is a city that is constantly changing. Some of these changes are internal and organic, but others have been the result of more profound changes in the political landscape in which the Jungle is deeply embedded, and yet over which it holds no control.

While cameras are a common sight, they are treated with great suspicion. Many people are wary of being photographed: some fear it may endanger their families should news of their escape reach home; others worry that evidence of their presence in France may be used against them should they eventually claim asylum in Britain; and others still feel ashamed of the situation they now find themselves in and do not want it immortalised in any resulting pictures.

It is not difficult to create photographs that evoke misery and suffering in the Jungle. And while such pictures might fit with what we think documentary photography ought to look like, such images usually take recourse to particular visual tropes and do little to deepen public understanding of a complex place at a time when greater understanding is so sorely needed. At the same time, it would be wrong to beautify what remains an utterly deplorable situation that exists not out of necessity but because of broken politics.

The photographs presented here are drawn from a much larger collection that spans four trips over six months. This selection is tempered by conversations I have had with some of those who live there about photography and the representation of the Jungle in the media. One friend from Darfur lamented the way in which many photographers came simply to ‘make their own business’. While I hope that the time I have spent volunteering on each of these trips is sufficient in his eyes to keep me out of this category, I also hope that the images here are seen as ones that are sensitive and respectful towards the issues so frequently voiced by the Jungle’s people. There are no portraits, nor any identifiable faces. In their place, I have tried to show traces of the many lives that are now collectively on hold. The impression left may be one of a desolate, depopulated landscape. But the reality couldn’t be further from that: beyond the edges of each frame is a vibrant and dynamic city in the making.

Police Lines, March 2016. Eritrean men watch through police lines as their shelters are destroyed. Following the partial eviction that took place in January 2016, the authorities announced a more significant intervention two months later: the southern half of the camp was to be evicted and demolished. They estimated that this area contained 800–1,000 people, but a census conducted by charities working in the camp suggested the figure was as high as 3,500. Many of those who lost their homes chose to leave the ‘Jungle’ and retrace their steps, often heading back to Germany, where asylum policy is thought to be more lenient. But many others moved into the little remaining space in the northern half of the camp, condensing those from different communities ever closer together. © Rob Pinney

Mario’s, November 2015. Mario’s is one of a number of restaurants that used to line the mud road running through the southern half of the camp. Many of the owners were formerly child asylum seekers who had been granted leave to remain in the United Kingdom but who had to leave upon turning 18 years old. Many now have asylum in France and, in some cases, Italy, but continue to run their businesses in the ‘Jungle’. Mario, who owned the 3 Star Hotel, was given his name on account of his impressive moustache. The hotel was among the hundreds of makeshift restaurants, businesses and homes that were destroyed as part of the eviction and demolition of the southern half of the camp in March 2016. Since then, and as the number of newcomers has started to increase once more, many of the remaining restaurants have opened their doors to people hoping to avoid the bitter cold of a night spent in a tent. © Rob Pinney

Burning Shelter, March 2016. As the eviction of the southern half of the ‘Jungle’ gathered pace, fires set by refugees and the use of tear gas by French riot police became commonplace. In the UK, the media have woven the persistence of fires into a narrative of destruction and lawlessness. But you might also see it this way: the decision to put a match to the walls of their shelters is arguably the only way refugees were able to exert at least a degree of agency over the inevitable destruction of their homes. © Rob Pinney

Shipping Container, January 2016. In January 2016, French authorities announced that they were going to clear a 100-metre ‘buffer zone’ between the edge of the camp and the adjacent motorway, which leads to the ferry port. At the time, charities working on the ground estimated that this would mean the displacement of more than 1,000 people. It was suggested that at least some of the displaced could move into these newly built converted shipping containers. Among residents of the ‘Jungle’, the reaction to the new containers – presented generally in the British media as a generous gesture – was decidedly mixed. Although they offered a warm and dry place to sleep for 1,500 people, the fear was that the registration information and biometric data that were gathered as the condition of a place (entry is granted by a handprint scanner) might be used against any refugee reaching Britain and making an eventual asylum claim under the Dublin Regulation. More generally, many also felt that by moving into the new containers they would isolate themselves from family, friends and the broader social environment of the camp. One resident described the containers as being ‘like a prison camp’. © Rob Pinney

Cricket in Afghan Square, January 2016. Although still bitterly cold, this was the first full day of sunshine after several weeks of rain, during what was for many refugees their first experience of a northern European winter. Under these conditions, once clothes become wet, they are almost impossible to dry out again – so many refugees made full use of this momentary shift in the weather to get out and play. The shipping container in the background houses a small fire engine, built and funded by volunteers from the United Kingdom and operated by a small crew of trained refugees. © Rob Pinney

Rob Pinney is a documentary photographer and researcher with a particular interest in war, post-conflict, displacement and migration issues. His project in Calais is ongoing, a portion of which is now available as a book, The Jungle, available at Call Me By My Name. To see the full series, visit his website. His Twitter handle is @robpinney and his Instagram account is @rob.pinney.