No Turning Back – diverging paths in Britain’s migration history

Standing at a crossroads

What have been the pivotal moments, the forks in the road, the lines in the sand in the history of migration in this country? And was the referendum on 23 June 2016 one of those moments?

The pivotal moments in a person’s, or a country’s, life are always compelling hooks to hang narratives on, and fertile ground for speculation. What if Hitler hadn’t turned his attention away from Britain and towards the Soviet Union in 1941? What if the Spanish Armada had had better weather and organisation? What if King Harold hadn’t had to face the Norwegians at Stamford Bridge a mere three weeks before facing the Normans at Hastings? What if England hadn’t beaten Germany in the 1966 World Cup final? The bookshelves in the historical section of bookshops and libraries are full of books that either speculate about what might have happened if the outcome of these events had been different or use the outcomes themselves as a means of defining the particular character of our country.

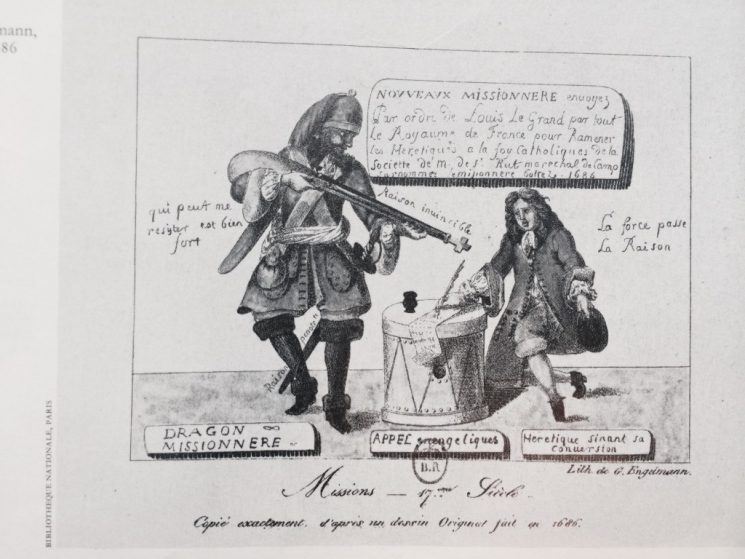

An image illustrating a French dragoon forcing a Huguenot to convert to Catholicism, following Louis XIV of France’s revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 and his sanctioning of these intimidating ‘dragonnades’.

Literature and personal stories are full of such moments, too, ‘The Road Not Taken’ by Robert Frost being one of the best known:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

In terms of this country’s relationship with Europe, two roads certainly diverged last June, and continue to do so, and the road we have taken as a country has made all the difference as far as campaigners on either side of the referendum are concerned. But what will the long-term difference be in terms of our attitudes to people born outside the UK? And are there comparable moments in our history where, faced with a stark choice, we took one road rather than another? And (last question for a while), if so, what were the outcomes of those decisions?

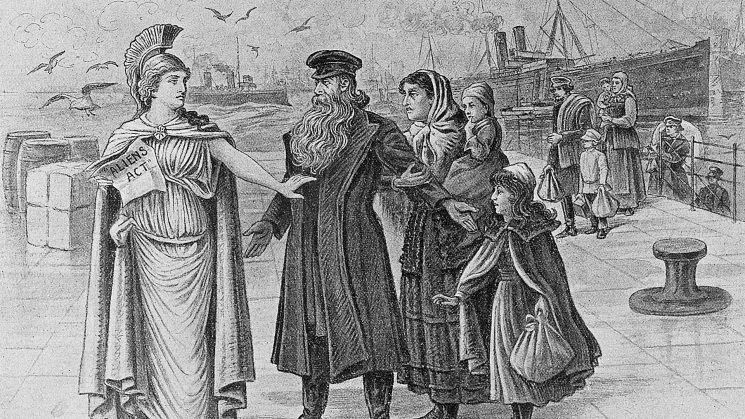

The original caption to this cartoon, printed in the wake of the 1905 Aliens Act, has Britannia saying “I can no longer offer shelter to fugitives. England is not a free country.” ©The Jewish Museum

These are some of the questions we plan to explore in a new exhibition called No Turning Back: Seven Migration Moments That Changed Britain, which we hope to open in the autumn of this year in our new space at The Workshop in Lambeth, London. The earliest of these seven moments is 1290, when, under the reign of Edward I, all Jews were banished from England; the most recent (if you can apply that adjective to a future date) is 2020, the date at which it is estimated that mixed-race Britons become the largest minority ethnic grouping. Moments in-between include the Huguenots, the East India Company’s arrival in India, the 1905 Aliens Act, the first scheduled long-haul jet service and Rock against Racism.

We’ve selected these seven moments because they seem to us to define key moments in our history but also because they echo so much of what is happening today. The expulsion of the Jews in 1290 was the only point in our history (so far) when we expelled a whole race or creed – but it has obvious parallels with what is happening today, both in the wake of post-referendum calls to East European residents and others to ‘go back to your own country’ and in the more negative connotations of ‘reclaiming our borders’. The arrival of the Huguenots in 1685 and after is cited as one of the great success stories of immigration – but how different was the reaction then to that mass arrival of foreign labour from the reaction now to today’s migrants, economic or other? And what are the factors that lead to one immigrant being accepted or successful while another is deported or deemed to have ‘failed’ to integrate?[/caption]

The title of our exhibition has since been appropriated by our prime minister and the advocates of a hard Brexit – but actually, when you take the long view of history, for all the defining moments from which there seemed to be no turning back there were a significant number of others when things just happened or changed because of a technological development (such as the availability of affordable, long-haul air transport), or an environmental disaster or because of the human capacity to form attachments. History is nothing if not unpredictable.

One of several blue plaques around the country that mark places associated with Jewish communities before their expulsion in 1290. © noli’s on Flickr

We’re conscious that others will argue that there are seven better moments we could have chosen for our exhibition – and we’d like that discussion to be part of the exhibition. There will be facts and figures, of course, but there will be many more personal stories, ideas and reflections – and we’d like that to be part of the visitor engagement in the exhibition, too. As with everything we’ve done so far, we are planning to enrol the visitor as much as possible in the content of what is on show.

For each of these moments we are already working with a team of academic and artistic advisers, teasing out the human stories of the event and attempting to reveal the consequences of that moment. As with our most recent exhibition, Call Me By My Name: Stories From Calais and Beyond, this will be a multimedia display with much new material, and with each section involving an interactive element for visitors to engage with.

We would love to hear from you if you:

- • would like to volunteer for the exhibition (or for the project)

- • would just like some more information

If you would like to get in touch, please contact Aditi Anand (aditi@migrationmuseum.org), Sue McAlpine (sue@migrationmuseum.org), Andrew Steeds (andrew@migrationmuseum.org) or Faiza Mahmood (faiza@migrationmuseum.org).

Leave a Reply