How long, o Lord, how long?

How long do you have to live somewhere before you are accepted as belonging there? A friend moved to a village in Devon 30 years ago and is now leader of the parish council. But she regularly finds her proposals or decisions challenged by another council member, who invariably begins his sarcastic intervention, ‘Well, as someone whose family have lived in this village for only the last 500 years . . . ’ My friend ruefully reflects that it will take her somewhere between 30 and 500 years to be accepted into the community in which she has chosen to raise her family.

Defining national identity is an equally tricky undertaking, whether for a person or a country. Post-referendum – and even before, as the UK citizenship test demonstrates – trying to work out what it means to be British is a bit of a national preoccupation, and one that British politicians routinely come unstuck on. It’s something that at least three distinguished friends of the Migration Museum Project (Robert Tombs, Robert Winder and Afua Hirsch)* have written about or are currently writing about – and they are not alone: type ‘Britishness’ into the search engine of Amazon and you’ll come up with just short of 100 books on the subject.

Defining national identity on a personal level is no less complicated. The passport you own is one factor, but many people who hold a British passport self-identify as any number of things (English, Welsh, Scottish, Irish, European, Jewish, Muslim, Black) before they identify as British – we are way beyond the Norman Tebbit test of which national cricket team you support.

And then, as Johanna Konta has reason to understand this Wimbledon, and numerous other sportspeople before her (Mo Farah, Greg Rusedski, all the way back to Basil D’Oliveira), being famous doesn’t bring you immunity from other people’s speculation about your identity. You may call yourself British, you may have a British passport, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that some journalists, and others, accept you as British.

Johanna Konta, the latest in a long line of British sportspeople to be questioned about their ‘Britishness’. © Telegraph

National identity is hardly homogeneous either – last year’s referendum and this year’s general election have shown how many different kinds of Britishness and Briton there are in this country. And this isn’t a new phenomenon. Let us take another of our distinguished friends, Sir Konrad Schiemann, who was orphaned in Germany and brought over to this country by his uncle, Werner von Simson: their experience was played out more than 70 years ago but will still reflect that of many people who are in the process of making the United Kingdom their home.

Werner had married an English woman in 1938 and came to England a year later, in June 1939, for the birth of their child in June 1939. He was in this country when war broke out and, having seen what was happening in his country of birth, Germany, and wanting no longer to be part of it, he stayed here. This didn’t stop him being rounded up along with other ‘enemy aliens’ living in Britain when Churchill gave his (in)famous order to ‘collar the lot’. Irrespective of how long you had lived in the country, or what your political allegiances might be, you were gathered together by ‘national identity’ and, in Werner’s case, sent to spend the war on the Isle of Man. The same thing happened to Konrad’s wife’s mother and grandfather – the musicologist O E Deutsch – who had fled Austria.

On the Isle of Man, German might have been a unifying language among the internees, but German Jews found themselves rubbing shoulders with Nazi sympathisers, communists with fascists.

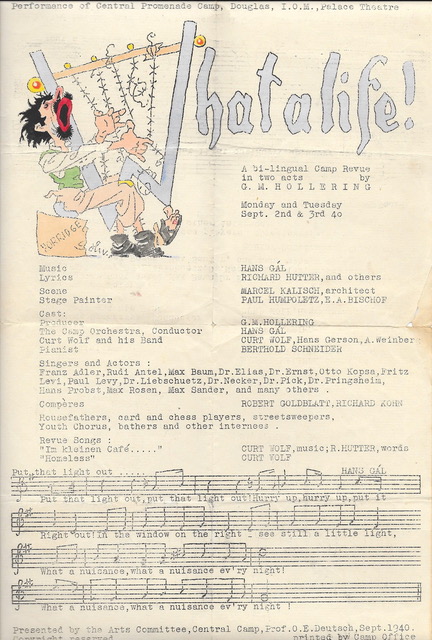

The programme notes for ‘What a Life!’, a camp revue put on in Douglas on the Isle of Man in September 1940.

(O E Deutsch’s story is one we have touched on before. While on the Isle of Man, he was involved in the production of What a Life!, a bi-lingual review that was put on in Douglas in September 1940. One of the songs from the review was performed by Norbert Meyn at the launch of our Germans in Britain exhibition in 2014.)

Werner brought his nephew, Konrad, to this country in the aftermath of the war. Konrad, born in Germany in 1937, lost both parents in the final stages of the war, his father being shot by partisans in Italy just months before VE day and dying shortly after, and his mother dying of a broken heart in Germany’s ravaged capital, Berlin, to which she had returned in the hope of being reunited with her husband.

Berlin in 1945 lay mostly in ruins. Konrad Schiemann and his mother were living in 64 Eichenallee, Westend, a house that was, as his uncle Werner wrote, ‘intact – it must be one of the very few houses which are’. © Monovisions

The circumstances of the newly orphaned Konrad’s removal to this country are conveyed in a series of letters, the first written in German by the 8-year-old Konrad himself (my translation):

10 Dez 1945. Liebe Tante Janni, ich werde Dir eine traurige Nachricht geben, dass Mutti krank geworden ist, weil wir ein Telegramm gekriegt haben, das lautet: das Papi grosses Pech haben musste, in den letzten Tagen von Partisanen überfallen zu werden. Er wurde am 30.4.45 verwundet und ist dann durch Versagen des Herzens am 3.5.45 im Teillazarett D in der Nähe von Padua gestorben (Grab Nr.178). Viele Grüße an Bettina, Andreas und Tante Hilda Dein Konrad.

10 Dec 1945. Dear Aunty Janni, I am going to give you some sad news. Mummy has become ill because we have received a telegram telling us that Papa had the really bad luck to be attacked by partisans in the last days [of the war]. He was wounded on 30 April 1945 and died on 3 May 1945 in the Teillazarett (hospital) D near Padua following a heart attack (grave number 178). All good wishes to Bettina, Andreas and Aunty Hilda. Your Konrad

Konrad’s mother, Beate, died on 10 January 1946, and Werner then volunteered to adopt the young orphan himself and bring him up in England as a member of his family, an arrangement in line with Beate’s wishes. In response to a letter from him, Werner’s father, agreeing with his suggestion, had this to say about the process of naturalisation (my translation):

Säge, 14 March 1946

My dear old Werner

I’d like next to say that I fully and unconditionally agree with everything you say. Now, the matter of your own naturalisation: I’ve always held the position, because of my own considerable experience of living abroad, that people who have come to feel really at home in another country can become essential promoters of good relations and rapprochement between the country of their birth and their adopted country only if they take on the nationality of their adopted country. Taking that further, even before these last twelve years, and especially before these last seven, I would always – since you are kind enough to value my agreement – have been happy about your becoming English. After these last years, in which sadly I have completely lost any connection (at least for the moment) with my fellow countrymen and women and can’t for now imagine – given the way in which they have behaved – how I will ever rediscover it, I approve of your actions all the more, an approval which is mixed with a slight sense of envy. What you have to say about Konrad’s future also meets with my full approval. On reading Ätchen’s will [Ätchen is Beate, Konrad’s mother], I said at once that for Konrad to be accepted into an English house and an English school would be possible only if he were himself to be brought up completely as an Englishman. That would have been desirable even in friendlier times; now it seems to me imperative. Ätchen’s wishes can be met only if the child were either to be placed under your guardianship in a German boarding school or allowed to become English as soon as possible.

For many immigrants, becoming English as soon as possible involves changing your family name to make it less ‘foreign’. With people from German-speaking countries, this process involves what Professor Rudiger Goering (previously Rüdiger Göring) in a lecture on George Frideric Handel (previously Georg Friedrich Händel) wryly referred to as ‘the inevitable shedding of umlauts’ and other German-specific sounds, such as changing ‘mann’ to ‘man’. Rather famously, one hundred years ago this week (17 July 1917) the Saxe-Coburg und Gotha family decided to change its name to the more English ‘Windsor’. Under the conditions of his mother’s will, Konrad kept his German name, an omission that Quentin Hogg (Lord Hailsham – a Conservative grandee and one of the longest-serving British politicians) mentioned on meeting Werner when Konrad was being sworn in as a judge. When Hailsham commented that Konrad had never ‘anglicised’ his name, Werner responded, ‘We’re not the royal family, you know.’

Sir Konrad Schiemann, barrister and judge and distinguished friend of the Migration Museum Project. He served the Court of Appeal and was also a member of the Court of Justice of the European Union.

Reflecting on his upbringing earlier this year, in an Inner Temple lecture on ‘What is Europe?’, Konrad Schiemann (who went on to become a barrister and judge, serving both the Court of Appeal and the European Court of Justice) confesses to be ‘one of the foreign-born workers and pensioners whose presence in this country clearly many find disturbing’. On paper, of course, he is the quintessence of Britishness – direct grant school in Birmingham, national service, Cambridge University degree, barrister, knighted in 1986 – and yet in a bizarre twist of events, and despite his having lived in this country for over 70 years, his British identity has come to be challenged since the referendum. As he said in the same Inner Temple debate:

Fortunately, throughout my time in this country, I have never felt myself hated – until, that is, the debates around the recent European referendum, when to my astonishment I found myself for the first time treated by some with whom I used to have a perfectly friendly relationship as an enemy of the people. I know German Jews who were equally astonished when the same thing happened to them in the 1930s.

In the months and years that follow, as we renegotiate our relationship with Europe and the wider world, those of us who call ourselves British – whether we have lived here for 30 years or for 500 – might do well to consider what it might mean to our national identity to define it so narrowly as to rule out so many who have – in sport, culture, commerce, law, politics and day-to-day living – enriched it beyond possible calculation.

* Robert Tombs, who gave our annual lecture in 2015, is the author of The English and their History, which is in many respects an attempt to provide a historical explanation of how we got to be the nation we now are. On 27 July, Robert Winder, whose book Bloody Foreigners was the early inspiration for the Migration Museum Project, publishes The Last Wolf: The hidden springs of Englishness, a book that attempts to identify the ingredients of the English national character. And early next year there is a new book by Afua Hirsch, Brit(ish): Why we need to talk about race, a book that also explores the identity crisis at the heart of Britain today, but from a racial perspective.

Leave a Reply